At a time when the world of sculpture was dominated by men, Louise Nevelson (1899-1988), a Ukrainian immigré in New York City, made a name for herself with her configured wall sculptures of painted boxes composed from scrap wood. A determined artist, Nevelson was in her sixties before the media recognized her work. A new exhibition at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, The World Outside: Louise Nevelson at Midcentury, seeks to reclaim the artist’s contribution to American art history.

Curated by Shirley Reece-Hughes, the show of over fifty sculptures and works on paper is divided into five thematic sections: choreographer, visionary, printmaker, community builder, and environmentalist. Visitors travel through Nevelson’s artistic journey, from her earliest wooden black boxes in 1950 to her site-specific installations that situated her within the avant-garde circles of that time period.

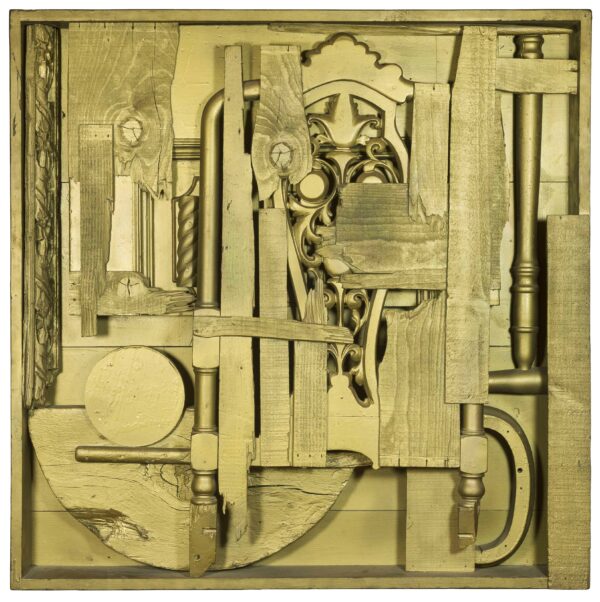

Louise Nevelson, “Lunar Landscape,” 1959–60, painted wood. Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, Purchase with funds from the Ruth Carter Stevenson Acquisitions Endowment, 1999.3.A-J

Nevelson is best known for her monochromatic sculptures in black paint. However, as she progressed, the artist experimented with white, such as her 1959 installation for the Museum of Modern Art, Dawn’s Wedding Feast, a few pieces of which are included in the Carter’s exhibit. Later, beginning in 1960, Nevelson experimented with gold, as seen in three works featured in the exhibit’s last gallery. Recent scholarship has suggested that Nevelson’s foray into gold-coated sculptures potentially has ties to Texas.

Louise Nevelson, “Royal Tide I,” 1960, painted wood. Peter and Beverly Lipman, Photo Courtesy Storm King Art Center by Jerry L. Thompson, © 2022 Estate of Louise Nevelson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Louise Nevelson, “Golden Odyssey,” 1961, painted wood, Amarillo Museum of Art, 39 ½ x 39 ½ x 4 ¾ inches. Bequest of Vera Beth Hicks, © 2022 Estate of Louise Nevelson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

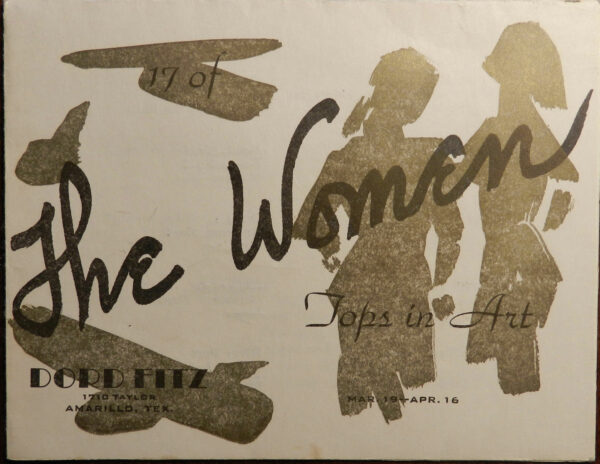

It was around this time that the artist first showed at the Dord Fitz Gallery in Amarillo. On display in the spring of 1960, The Women: Tops in Art was an all-women group exhibition of 57 works by an impressive roster of 18 female modernists, mostly New York-based, including Elaine de Kooning, Helen Frankenthaler, Ethel Schwabacher, Hedda Sterne, and Miriam Schapiro. And, of course, Louise Nevelson. During the show, a group of Fitz’s students pooled their money together and collectively purchased Nevelson’s Moon Garden (1958-60). It was this show and sale that cemented the artist’s decade-long relationship with the Panhandle community, which she visited at least seven times between 1960-1972, showing art, giving talks, and leading workshops.

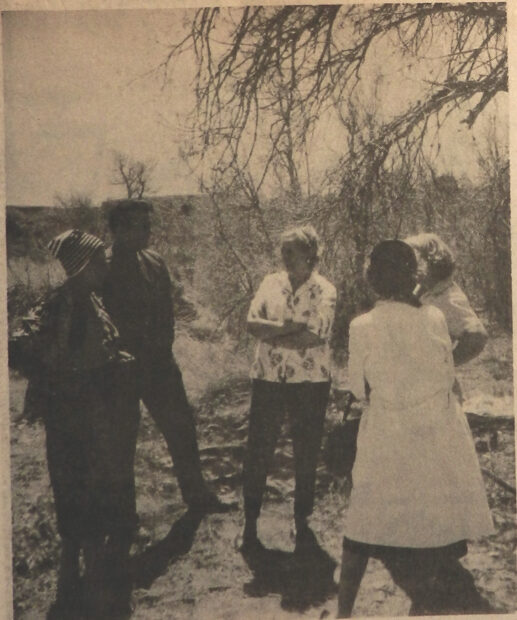

Fitz describes one of Nevelson’s first visits to the High Plains:

“We took the visiting artists to Stratford, Texas. Then we all got in an old school bus and went out twenty rough miles to the center of the Durr Ranch. There, in the middle of a level cow pasture, six cowboys, in their cowboy work clothes, were preparing a lunch for us over an open fire… That evening the Stratford art students prepared a great feast for us which we ate at the County Barn on the fairgrounds. After dinner, the community came to meet the artists and to enter into a discussion of art conducted by the visiting artists.”

Catalog for “The Women: Tops in Art,” 1960, Dord Fitz Gallery, Amarillo, Texas. Courtesy of the Western History Collections, University of Oklahoma and the Family of Dord Fitz.

Women artists from New York at the Durr Ranch near Dumas, Texas, Spring 1960. (Photographer unknown.) From the collection of Carolyn Fitz. Third from left, Elaine de Kooning; third from right, Louise Nevelson; seated to the left of Nevelson is Martha Jackson.

In 2022, Amy Von Lintel and Bonnie Roos published Three Women Artists: Expanding Abstract Expressionism in the American West, which features Nevelson and explores her relationship with the arts community in Amarillo in the 1960s. It’s her ties to the Lone Star State that, as a Texan, make Nevelson’s story that much richer for me.

I recently talked with Von Lintel, professor of art history at West Texas A&M University in Canyon, to discuss Nevelson’s connection with the Panhandle town, the artist’s impact on the local art scene, and the influence Texas had on Nevelson and her work.

Leslie Thompson (LT): How did Louise Nevelson first develop connections with Amarillo?

Amy Von Lintel (AVL): Amarillo gallery owner Dord Fitz would make regular visits to New York City, where he was affiliated with the Burr Galleries that artist Patricia Bott was running. When he came into town, he met Elaine de Kooning and Jeanne Reynal [the other two artists featured in Lintel and Roos’s book] with his group of students from the Panhandle, who always wanted to do studio visits. Somehow Nevelson felt coerced into dealing with this person until she met him. And then she was kind of like, “Oh, wow. Ok.” And by 1960, Fitz was doing an all-woman show, and it included all these women. But Nevelson was kind of the showpiece.

The Amarillo community ended up buying that showpiece, Moon Garden. It had been part of the 1958 installation Moon Garden + One. All of the bits and pieces were reorganized when she deinstalled that. It made it into MoMA with the famous Sky Cathedral. That’s another part of it. Our part that came to Amarillo was a reorganized part that she decided to bring to this 1960 all-woman show in Amarillo, and she came, too. She didn’t just ship the thing. So somehow, Dord convinced her that it was worthy to one, send a piece, and two, come. And he paid her bill to come.

In the 50s, Nevelson was struggling to get sales. She started getting shows in 1958 that were well-received and critically acclaimed. But to sell the stuff was hard. So the 1960 show and sale in Amarillo was of financial significance to her.

Louise Nevelson, “Moon Garden,” ca. 1959, painted wood, 8’ 7 3/4” x 8’ 18 inches. Amarillo Museum of Art, Gift of the Area Arts Foundation in honor of Dord Fitz

LT: During your research, did you find any evidence of what the town thought about Nevelson, both the artist and her artwork? And did you gain any sense of Nevelson’s perspective? What were her impressions of Texas?

AVL: We have more statements about Nevelson from fans and students than we do from Nevelson about them. It’s because she wasn’t a letter writer.

What we only have is that Dawns + Dusks book — her assistant Diana MacKown recorded her and then transcribed the interviews. There’s a note between Diana MacKown and Dord Fitz that says, “Dord, I can’t wait to put the section in the book on Amarillo.” And then it doesn’t show up. I don’t know who cut it. I don’t know if it was cut by a publisher or if MacKown never got the stuff from Fitz in time, or if she deemed it unworthy in the end. But there was intended to be a whole section in that bookabout Amarillo, and it got dropped out. So it’s missing that voice of hers about Amarillo. We have a few letters, but not a lot.

_____________________________________________

Dear Dord, I am coming closer to the conclusion of the book on Louise that I have been working on. She has mentioned how important the years in your relationship with her have been and the placement of your beautiful wall in Amarillo. I know that she gave several talks in Amarillo over an extensive period of time and would be most grateful if you could send me, and of course you would get full credit, copies of the tapes. Louise and I feel it would be such value in the project. It was fun to see you in New York and I guess you will see Louise soon again in the West.

– Diana MacKown to Dord Fitz, October 24, 1973

_____________________________________________

But mostly it’s write-ups in the paper, or people who talked about how flamboyant she was when she came to town. There’s lots of witnesses about that — what Texas thought of her. They treated her like a princess. She was so interesting and seemed so exotic, and they ate it up and loved it.

But then she would get down to business. There are these wonderful photographs of her getting rid of all of this exotic clothing, and in the studio with a stocking cap on and at work. She’s with this woman, who to me looks like a frumpy housewife, and they’re making a box. Nevelson is teaching them to make boxes. So this is the other story of her as an educator. Even when she was getting all the acclaim and making money and showing in Germany and Paris, she still made it back to Amarillo to teach these classes. At that point in her career it wasn’t a financial necessity. I think she actually enjoyed it.

LT: In your book, you speculate about how Nevelson’s gold work — which she began in the 1960s — may have some ties to Texas. Can you talk about that? How did Texas influence Nevelson?

AVL: We don’t have her saying that directly. What we have is that both of her biographers note that Nevelson’s sister discloses that she talked about her gold pieces as being inspired by the faucets in Texas ranch houses. Because they were gilded. This is an idea of showiness, and also surface coating. Nevelson never gilded her boxes, she just spray painted them, kind of like cheap gold. She was always talking about how “it might look like I’m put together but underneath I’m held together by safety pins.” Or she talked about how when she was an immigrant child they told her the streets in America are paved with gold. And then she showed up and they weren’t.

LT: Gilded faucets. That’s so Texas. The flash! Especially in the 50s. You’ve also pointed out that in some of her work around this time we begin to see Nevelson using stocks of wooden rifles. Those aren’t New York handguns. They’re the kind of rifles one would find on Texas ranches.

AVL: Right! She knew Texas. Not from afar, but from within. I think she was perceptive about that flashiness. But also, she was flashy. She found this familiarity with Texas. She would wear big jewelry and so would Texas women, even if they weren’t dressing like she did. And they embraced her for that. That flamboyancy is that gold work coming through.

If you look at the buyers of the gold work, New Yorkers were not buying them. Texans were. There are several pieces that stayed in the Panhandle because people were not rejecting the gold like people in New York, who couldn’t figure out what she was up to. Why are you so flashy? Maybe because she’s been exposed to Texas flash.

LT: What impact do you think Nevelson had on Amarillo?

AVL: I think she befriended many people. I-40 came through town in the 1960s, at the time that Dord Fitz had his first gallery, so he had to move it for the highway. Betty Bivins Childers, one of the founders of the Amarillo Museum of Art, allowed Nevelson’s Moon Garden to live in her house while Fitz was rebuilding his gallery. Bivins and Nevelson became friends, and when Moon Garden was reinstalled in Dord’s new gallery, Nevelson came back to help with the reinstall. Her presence was not just that of a teacher who sweeps in and out.

The people who bought her work knew her well and loved her. And we have lots of witness of that. She made an impact on the students she was teaching. These students were not young kids, but well-to-do adults. They were so open to abstraction, open to her philosophy. They just loved her.

We conducted lots of interviews. So many people in this area have stories. There was this one woman who was a little girl when she met Nevelson. And all she remembered was her caterpillar eyelashes. Nevelson would put on fake eyelashes and so much mascara that her eyelashes were like worms to this girl. People remembered her.

Student entertains Louise Nevelson, photographer unknown. Clipping from the Dord Fitz Collection. Image courtesy of the Western History Collections, University of Oklahoma and the Family of Dord Fitz.

LT: During your research on Nevelson, of the scholarship that’s published, did you see any mention of Nevelson’s connection to Texas?

AVL: Yes, because people knew that she came to Amarillo. But they didn’t know the references that we do. So it’s not this hidden thing that Nevelson came to Texas. It just wasn’t interesting to them. The thing about the faucets is a footnote in the back of a book. So Texas isn’t totally missing, it just wasn’t a focus.

LT: What was it that sparked your interest to dive deeper into this?

AVL: The sheer number of pieces by these women [Louise Nevelson, Elaine de Kooning, Jeanne Reynal] in our area in private collections and the people who would talk to us about these experiences. It was a community story.

We were surprised by how rich the stories were once we started scratching the surface. There was enough there to make a whole book out of it — we didn’t have to stretch them.

My interview with Von Lintel merely scratches the surface of one part of the story. If you want to learn more about Nevelson’s relationship with Amarillo and the Panhandle community’s connections to the New York art scene, I highly recommend checking out Three Women Artists: Expanding Abstract Expressionism in the American West.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

The World Outside: Louise Nevelson at Midcentury is on view through January 7, 2024 at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth, Texas.

1 comment

Great interview! What a rich and interesting history. I can’t wait to dig into the book.