Who are some of the best-known artists among the general public? Vincent van Gogh. Pablo Picasso. Andy Warhol. Diego Rivera? Along with (and perhaps because of) Frida Kahlo, Rivera is perhaps one of the most popularized artists from Mexico. This hyper-focus on Rivera and Kahlo can be a double-edged sword: it is important to have Mexican representation in the broader art canon, but, at least in the U.S., the mythologized narrative around the duo overshadows much of the rich, nuanced art history of the country. And, though the (often tumultuous) long-term couple clearly influenced each other’s work, the continual pairing of the artists leaves little room for them to have individual voices and stories.

Frida Kahlo, ” Frieda and Diego Rivera,” 1931, oil on canvas, 39 3/8 x 31 inches. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Albert M. Bender Collection, gift of Albert M. Bender. © 2022 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

It seems fitting then, that as Kahlo has received more individual attention, that the same is necessary for Rivera. So, despite the fact that a solo exhibition of Rivera might feed into the history of hyperfixation on him as the archetypal Mexican artist, I was excited to see that the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art have co-organized an exhibition focused (almost) exclusively on his work.

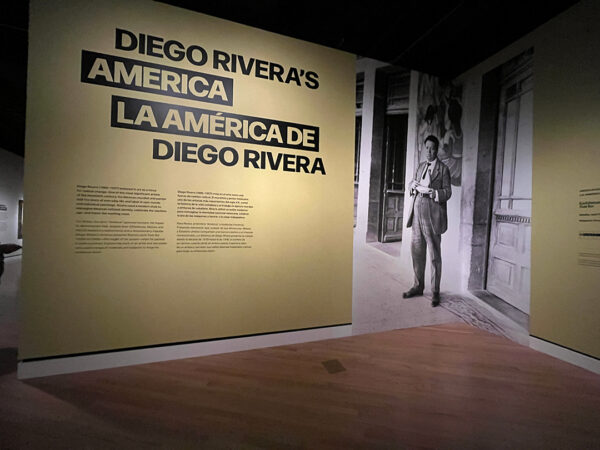

Diego Rivera’s America is the first major show to concentrate solely on Rivera’s work in over two decades. The exhibition presents over 130 of his pieces, including drawings, paintings, and projections of murals (it also features three works by Kahlo, including an iconic self-portrait of her standing next to Rivera). The title of the show explores the connectivity between Mexico and the United States, rooted in the history of the land and Indigenous populations, and continuing through the present-day exchange of goods and culture. Though often people in the U.S. use the term “America” to describe their country, or even “American” to describe the people living in their country, these terms have wider meanings beyond our borders, as they relate to North, South, and Latin America. Viewers expecting to see paintings by Rivera of the U.S. may be surprised that the exhibition begins with sketches, paintings, and murals created in Mexico, depicting the people, places, and customs of the country.

The exhibition is organized into the following themes: South to Tehuantepec, Mothers and Children, Murals on Paper, The Making of a Fresco, Rivera in California, Pan American Unity, The Proletariat, and In the Studio. While the vibrant colors, stylized figures, and narrative scenes that Rivera paints are mesmerizing, the most crucial part of the show to understanding Rivera were the drawings made in preparation for his murals.

Walking into the gallery at Crystal Bridges, one of the first walls is covered with large-scale sketches of hands in various poses for the 1922 mural Creation, which was Rivera’s first government-commissioned mural. The piece is still in existence inside the Simón Bolívar Amphitheater in the Colegio de San Ildefonso (then called the National University of Mexico) in Mexico City. Leading with these hands brought an immediate humanistic sense to the space, like a warm greeting. As each of these pieces measures about 20-by-25 inches, they also provide a sense of scale for the mural, which is presented via a not-to-scale projection. Instead of a static projection, this piece was activated, featuring a video of two musicians sitting on a stage in front of the mural and playing their instruments. This presentation invited visitors to sit and spend more time with the projection than that they might have otherwise. I found myself using the drawings of hands as a scavenger hunt, scanning the mural to identify which hands belonged to which figures.

The line work, shading, and textural details of the chalk, charcoal, and pastel drawings revealed a realistic approach not often associated with Rivera’s more stylized depictions of people. Throughout the show, preparatory drawings for paintings are also presented, and the range is exquisite. From bold contour line drawings to gestural sketches and more refined studies, the works on paper reveal the artist’s range and process. They feel like an intimate peek behind the curtain of the facade of Rivera as icon.

Along with the breadth of Rivera’s work, the exhibition packs in a lot of context. Large text panels outline some of Rivera’s broader ideas and themes, while providing important historical and political context. Among the paintings by the artist, the show presents sketches and projections of murals, including the preliminary drawings for The History of Mexico, a three-part mural at the National Palace in Mexico City; The Making of a Fresco Showing the Building of a City, at the San Francisco Art Institute; and Rivera’s last mural created in the U.S., The Marriage of the Artistic Expression of the North and of the South on This Continent, often referred to as the Pan American Unity mural. In different ways, each of these murals makes connections between the U.S. and Mexico. The History of Mexico, most of which was painted in 1929-1930, tells stories of Mesoamerica prior to the Spanish invasion — featuring the beliefs, culture, struggles, and successes of the Aztecs — through then-present-day class conflict between industrial capitalism and communist values. (The depictions of contemporary issues and potential futures were painted in 1935.) The largest panel references the turbulent struggle for control over the country, including the Spanish Conquest, the U.S. invasion, and the Mexican Revolution.

Created in 1931, in the early years of the Great Depression, The Making of a Fresco at once uplifts the arts and laborers. Alongside scenes of drafting, planning, and creating a mural are depictions of steel workers. The piece reveals the effort and people who make a public art piece come to life, and in doing so highlights the economic effects of art. Though less overtly, by focusing on workers, the mural also makes connections between the social and political issues facing the U.S. and Mexico at the time. The depiction of a towering laborer controlling a machine and wearing a red medallion on his shirt pocket makes it clear that Rivera’s Communist leanings shaped the ideas behind the work, though it feels as if the artist has made an attempt to tone down the political elements into a design more palatable for the U.S. audience.

Diego Rivera, “Making a Fresco,” 1931, at SFAI’s Diego Rivera Gallery. Image credit: Joaquín Martínez/Flickr)

Seen now, in retrospect, The Making of a Fresco foreshadows the conflict between Rivera and the Rockefellers regarding the 1933 Man at the Crossroads mural. This mural’s sketches, which were approved by the Rockefellers, are included in the exhibition, and wall text explains that following Rivera’s inclusion of a portrait of Russian revolutionary Vladimir Lenin, the project was halted and later removed from the wall.

Diego Rivera, “The Marriage of the Artistic Expression of the North and of the South on This Continent,” also known as “Pan American Unity,” 1940. Courtesy City College of San Francisco; © Banco de México Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico City / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; Image: Cultural Heritage Imaging

Painted in 1940, The Marriage of the Artistic Expression of the North and of the South on This Continent was Rivera’s last mural in the U.S. The piece was painted live as part of the Golden Gate International Exposition on Treasure Island, a World’s Fair (unsanctioned by the Bureau of International Exhibitions, but designated as such by President Roosevelt and Congress) that originally ran from February through November 1939 and then reopened from May through September 1940. Measuring 22-by-74 feet, the massive mural was painted on panels, to be portable. Bringing in aspects of his previous murals, this piece references Indigenous cultures, political histories, cultural achievements, and workers of both the U.S. and Mexico.

Alongside individual artworks, smaller labels provide deeper information about Rivera’s process and the people and practices he depicted. It was a treat to see The Embroiderer, a painting which had been in a private collection for over 90 years prior to its acquisition by the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston last year. Though the piece fit in with Rivera’s other scenes depicting everyday people engaged in work, like grinding masa or selling food at a market, the vivid red of the tapestry and the embroiderer’s shirt stood in contrast to the colors and mood of other pieces in the gallery.

Perhaps the most unexpected and surreal aspect of the show was the inclusion of costumes designed by Rivera for a modernist ballet titled H.P., for Horsepower. Produced in Philadelphia in 1932, the ballet told a Pan-American story that was promoted as a narrative of cooperation between North and South. Some attendees came away with a utopian view of the relationships between the continents, with the South supplying natural resources and the North manufacturing goods that benefited everyone. Others perceived the play to be an indictment of the North as a colonial and aggressive force against the South.

Rivera’s costume designs of a banana tree, with large ripe bananas covering the figure’s back and arms, and a tobacco figure cloaked in brown tobacco leaves with a tall beehive-like cigar as a mask and headpiece, were commissioned in 2022 for the exhibition, marking the first time they have been reproduced since the 1932. They were created by Mexican artist Toztli Abril de Dios, based on Rivera’s designs.

The exhibition closes with a section of paintings made in the 1930s and 1940s in the studio Rivera moved into following his and Kahlo’s 1933 return to Mexico City from New York. This was when they moved into their infamous twin houses connected by a bridge. The choice of bookends for the show – Creations at the start, and works completed after returning to Mexico City at the end – is a tidy presentation of an important sliver of Rivera’s career.

While going into the exhibition I knew the broad strokes of Rivera’s life and artistic journey, Diego Rivera’s America provided an in-depth look at the scope of his oeuvre, the important social contexts in which he created his often politically motivated pieces, and highlighted his (and others’) efforts to bridge the cultural divide between Mexico and the U.S., two countries that have a long history that borders cannot erase. For audiences who are accustomed to the often reductive narrative of Rivera and Kahlo, the show carves out space to present Rivera’s unique artistic vision and journey. And for those already familiar with the intricacies of Rivera’s artistic practice and process, the exhibition maps out parallels across decades of his work.

Diego Rivera’s America is organized by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art and is curated by James Oles, guest curator, with Maria Castro, assistant curator of painting and sculpture, SFMOMA. The show is on view at the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas through July 31, 2023.

2 comments

Diego Rivera was not Sonny to Frida’s Cher! He was/is one of the most famous and iconic artists in the world and is in little need of rediscovery.

Your review was excellent. My wife and I saw the exhibit recently and your analysis brought back lots of our thoughts on this spectacular exhibit.