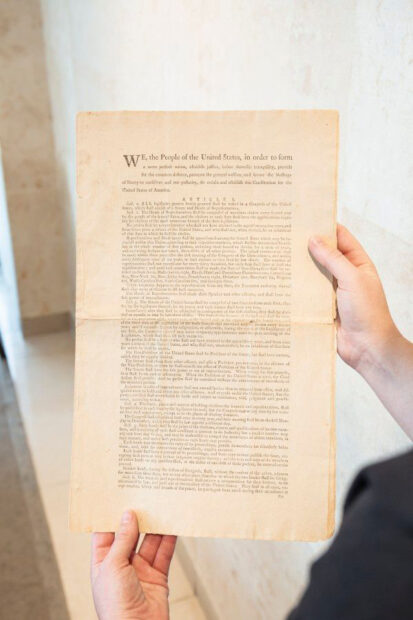

Installation view of “We the People: The Radical Notion of Democracy.” Image courtesy of Crystal Bridges.

It starts with a simple wall caption that reads “The Road to Democracy.” From there, We the People: The Radical Notion of Democracy, guides the viewer along a sweeping American timeline, both textual and visual, that stretches from early colonialism to late capitalism. It is a long and winding road.

At the heart of We the People, on view at the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas, is an original copy of the U.S. Constitution, on loan from hedge fund titan Ken Griffin, who purchased the item from Sotheby’s late last year. In an auction battle that lasted all of eight minutes, Griffin outbid a crew of 17,000 cryptocurrency investors for the $43.2 million acquisition; now he wants to share it with as many people as possible. The rare relic is currently being shown alongside other historically significant U.S. documents, as well as works of art spanning 300 years, from portraits of Native American leaders and Founding Fathers, to Suffragettes and Malcom X.

Organized by Polly Nordstrand, Crystal Bridges’ former curator of Native American Art, the ideas put forth in We the People offer a broad — and perhaps unexpected — narrative of shared, sometimes competing, histories. The chronological presentation begins with the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy and its enduring influence on American democracy, which, in 1987, the U.S. Senate formally acknowledged was owed a “historical debt.” A fascinating fact — and the first I’ve heard of it.

“We’re in this era where people tend not to trust,” Crystal Bridges’ chief curator Austen Barron Bailly tells me during our recent call. “We are very invested in providing historical and artistic evidence of the past to give people their own tools for navigating their beliefs and opinions and knowledge, from civics to art history.”

John Dunlap and David Claypool, “The Official First Edition of the Constitution,” 1787, ink on paper, 16 1/8 x 10 1/8 inches. Private Collection. Photography courtesy of Sotheby’s, Inc.

The displayed documents are surrounded by artworks that, at times, bolster the deep-rooted meaning of their words, and at other times, question them altogether. We the People is split over two galleries, with the first space doing the bolstering and the second doing the questioning. In that first gallery, a timeline from 1680 to 1791 runs along the wall — the years leading up to the Revolutionary War and directly after — and chronicles the events that came to define the early pinnacle of America.

Toward the front of the space, the Declaration of Independence and Articles of Confederation are encased directly in line with a replica Two Row Wampum belt — in essence, a Native constitution — that references the 1613 agreement between the Dutch and Haudenosaunee. The belt’s parallel purple rows signify the principles of peaceful coexistence that underpinned their treaty, and later contributed to the philosophical foundation of the U.S. Constitution.

Installation view of “We the People: The Radical Notion of Democracy.” Image courtesy of Crystal Bridges.

The Constitution itself is the gallery’s center point, with John Trumbull’s Portrait of Alexander Hamilton (1792) on one side and multidisciplinary artist Shelley Niro’s Borders (2008) on the other. Niro, who is Mohawk — one of the six nations of the Haudenosaunee — has in a way modernized the Wampum belt with these four black-and-white photographs, each one showcasing two outstretched arms in various stages of reaching for one another before they ultimately join hands.

Toward the back of the gallery, Chester Harding’s A Portrait of James Madison (1829-1830) is installed directly above The Federalist Papers, flanked by paintings of Native leaders Red Jacket and Joseph Brant. Adjacent to The Federalist Papers, a wall panel titled “Conflict and Compromise” offers an intentional vantage point, explains Bailly, for the viewer to contemplate all the historic forces at play. “From here, as you look at Madison, you can see Washington and Red Jacket. You can see John Vanderlyn’s painting of Niagara Falls, which is the Haudenosaunee homeland, and Richmond Slave Market Auction, by a British painter [Lefevre James Cranstone] — even though slavery is not in the Constitution, the institution of slavery is essential to how it was formed.”

Jacob Lawrence, “. . . is life so dear or peace so sweet as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery?—Patrick Henry, 1775,” Panel 1, 1955, from “Struggle: From the History of the American People,” 1954–56, egg tempera on hardboard. Collection of Harvey and Harvey-Ann Ross. © 2022 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

In the exhibition’s second gallery, the Emancipation Proclamation and the Thirteenth Amendment, which together formally abolished slavery, are presented side by side. The Bill of Rights (the first 10 Amendments to the Constitution) shares the floor with Elizabeth Catlett’s wood sculpture Black Unity (1968) — a carved clenched fist on one side and two faces on the other. Across the way, Jasper Johns’ iconic American flag looks out onto the vista of contemporary American art.

Sandow Birk’s sizable Monument to the Constitution of the United States (2012), intricately transcribes the document and its amendments upon an imaginary yet vaguely familiar edifice, complete with rotunda. Up close, its hand-drawn details reveal some of the more bizarre footnotes in recent history — Dick Cheney’s duck hunt incident, for instance — packed densely with satirical illustrations that act as both a send-up and celebration of American politics and culture.

Shelley Niro, “Treaties,” 2008, printed 2022, inkjet print, 24 x 54 1/8 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

These side-by-side examinations offer an ideological prompt more than a history lesson, as modern voices mix with founding texts to try and work it out. Six panels by midcentury painter Jacob Lawrence, depicting key events in the early days of the Republic, echo the civil rights movement of the 1960s, while Gordon Parks — Life magazine’s first African American photographer — and Chicano photojournalist Luis Garza offer up less visible stories from that same era.

Two works by Roger Shimomura recall Japanese American incarceration — including that of his own family — during World War II. In Gordon Hirabayashi, American Patriot (2015), the artist pays homage to Hirabayashi, who refused to enter an internment camp during the war and was subsequently convicted and jailed. He appealed his case in 1943, which went all the way to the Supreme Court, where all nine Justices ruled against him. In 1987, a federal appeals court overturned the conviction.

Installation view of “We the People: The Radical Notion of Democracy.” Image courtesy of Crystal Bridges.

The color lithograph shows a grinning Hirabayashi against a backdrop of stars and stripes, the Supreme Court Building practically perched on his shoulder. It is accompanied by a quote: “There was a time when I felt that the Constitution failed me, but with the reversal in the courts and in public statements from the government, I feel that our country has proven that the Constitution is worth upholding … I have more faith and allegiance to the Constitution than I ever had before.”

We the People was in mid-installation when Roe v. Wade was overturned by the Supreme Court this past June in a 6-to-3 decision, a stunning reminder that these complexities — and contradictions and hypocrisies — aren’t going anywhere anytime soon. Innate tensions and ongoing struggles have always been central to our story. At a time when all sides are at odds, Hirabayashi’s words offer hope for this radical notion of democracy. And for the long road ahead.

We the People: The Radical Notion of Democracy is on view at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, AR until January 2, 2023.

2 comments

As a longtime museum goer, former museum professional and artist, I can easily say that Crystal Bridges has done more to advance racial equity than any museum I know. Not only in its temporary exhibitions, like this one, but also with innovative installations of its permanent collection.

Thank you