Over the last year, Dallas-based artist Jen Rose, best known for her elegant and prolific work in porcelain, has been materializing monsters. Out of warp and weft and clay and fire, her ideas about the individual, the body, our desires, and our relationships to each other all take form under Rose’s steady hand and her expansive imagination.

I had the opportunity to catch up with her in her studio last month and discuss her recent body of work, included in her current solo exhibition at CAMIBAart Gallery in Austin titled Since Last We Met. After finding a discarded loom in her neighborhood, Rose began experimenting with weaving and rug-making techniques, drawing on her previous weaving experience in college.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Anne Lawrence: How did you first come to the idea to combine the two — ceramics and textiles?

Jen Rose: I’ve always been very inspired by Nick Cave and his Soundsuits. I’ve thought for a long time about how he might make those and how he might add other materials, like twigs to the fabric. I’ve been making thousands of things and then putting them together in some sort of assemblage, and that’s been working okay. But, the Holy Grail was to find a way for me to make those permanently attached with as little support and structure as possible. I started realizing as I was creating this webbing out of fabric that this was the perfect time to start adding things. It started from thinking that maybe this is how Nick Cave makes those sound suits, and then going on from there.

AL: You had a problem to solve and you were trying different techniques and ways, right? So, tell me a little bit about how this work is different from your other work? Adding the textile — what does that allow you to do that’s different from what you’ve done before?

JR: Everything that I’ve done has been attached to a wooden base or installed directly into the wall, and that doesn’t allow for manipulation of the object itself. These pieces are interesting because of the way they’re created. They are on a flexible fabric, and they’re one with the fabric, and so I can move them and manipulate them in different ways. That’s been really interesting. I started off with a traditional loom and then, based on my experiments, I figured out how to take the basic structure of the loom, turn it vertical, and take the warp off the loom so I can weave on both sides. There are other experiments that I can do with that as well to create either more or less densely populated sculptures, or work in the round. So, it gives me more options.

AL: I’ve heard you use the word “manipulatable.” Why is that important to you?

JR: When you manipulate these sculptures, it brings life to the piece simply because you allow the viewer to have some sort of power in adjusting the work. These pieces have choices to them. And so those choices, once they’re out of my control, fall to the control of the viewer and the owner of the piece. They have a life beyond me.

AL: How do you incorporate photography? What’s that relationship there?

JR: That’s a new thing I’ve been experimenting with and think that the photography allows me to tell a story about the piece. The first two pieces I did on the loom were very much driven by the pandemic. All of these pieces have been called Tiny Monsters. They are ideas about what’s happening with the pandemic and how that’s affecting us and how that’s folding into ourselves and our bodies. The first two photographs I did were based on figures wearing the pieces or interacting with them in some way. I feel like that was important because of the idea of the pandemic being so visceral and affecting the body.

AL: I can’t help but make the connection between using a loom to make textiles and then the relationship to the body. Can you speak to that?

JR: It’s something that I don’t know that I’ve thought consciously about in in a lot of ways. So definitely there’s the idea of the preciousness of weaving a cloth. Then if you think historically about clothing, in medieval culture, that was some of the most precious material or precious objects that people owned, other than their bed. So having these things that are woven and then worn creates a preciousness to them in a certain degree. And also, weaving these things that I like to refer to as sort of living objects or these monsters — it’s again creating this act of giving it life by creating a piece of clothing for it.

AL: I noticed that the early early pieces look more, or remind me more, of tentacles, or hair, or course fibers. What was inspiring you with those shapes?

JR: Those little squigglies are pretty fast to make, but there’s also the idea that they’re so messy. They’re like a ball of chaos when they’re all put together, and there’s not any kind of the discernible rhythm to them because they’re all going in different directions. That was something that I was attracted to in thinking of the pandemic as a time of chaos.

AL: I’ve noticed that in the more recent work, the shapes have become more defined. How does that work relate back to some earlier installations?

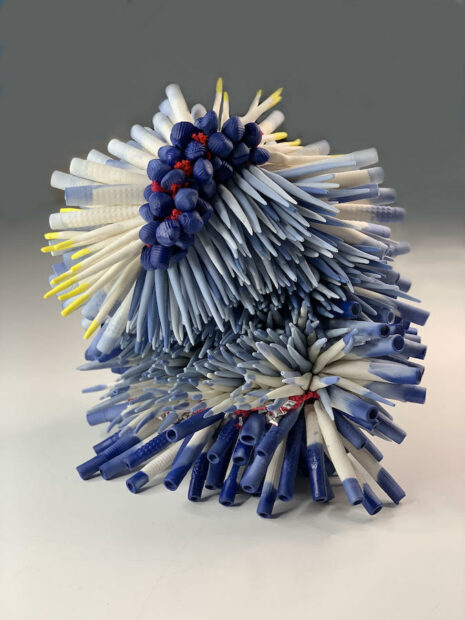

JR: I’ve always been fascinated with the way porcelain works as a hollow form and the light that transfers through it. So these tubes started out as installations I was putting in trees and I was fascinated with the way the light would catch the tubes at certain times of day, and that porcelain would glow. There is also the idea of tube-dwelling beneficial insects, which I’m really interested in. So the tubes in this body of work started off with an idea of how could I make a nest for insects, but also create these really fascinating sculptures.

Additionally, there’s the idea of the sea worms on the hydrothermal vents under the ocean. Those are really fascinating too, and these relate to those, because if you look at the sea worms, they’ve got these red tips on top of white tubes, and the ones that I’ve been working with have the blue tips on top of white tubes.

AL: So tell me a little bit about that. I think you mentioned it was a cobalt, so it’s actually a mineral?

JR: The blue is cobalt-based and that’s something that’s very historical in ceramics. It goes back to the blue-on-white Chinese ceramics of the 16th-17th centuries, but it’s also interesting because that particular cobalt is a water-solvable salt and will absorb into the clay body. So, if you break one of those tubes, that blue penetrates all the way through the clay body. For some reason that’s more fascinating to me because it’s absorbing and it’s internalizing this cobalt instead of the color just being a surface coating.

AL: I think it also gives it a really interesting surface quality. Can you tell me about that?

JR: It’s almost like skin — how light reacts with porcelain differently than it reacts with other kinds of clays. It will penetrate a layer of the porcelain, just like skin will absorb a little bit of the light. When you have that color permeated all the way through, there’s not a surface that that can be scratched off.

AL: With your recent pieces that you’ve been weaving, I’ve noticed that your colors are really bright, with the nylon rope. How did you come to that?

JR: I was working with linen thread, which is beige, and it didn’t have any kind of color, and it didn’t really have a voice. But then I discovered all of this nylon thread, and I thought those were interesting because if these pieces ever go outside, that nylon thread is not going to decompose. But I just fell in love with all of the colors that this nylon came in, and the voice the color had along with the piece. It created another dynamic and another dialogue with the piece itself. Not only do you have these growths coming off of the fabric webbing, but the fabric webbing itself starts to talk.

AL: Right. It starts to remind you more of something like a fishing lure, like tying flies. So tell me about fishing.

JR: It’s funny, because I have been fishing with my family since I was a little kid. In fact, I was at a restaurant one time and there was a psychic there. I went up to get my cards read, and she was like, “I’m seeing art and fishing.” I had just come back from a fishing trip with my family.

When we go fishing, we usually fish at night. We’ll go out about 10 p.m. and we’ll turn on the lights that shine into the water and that brings all the shrimp up. You start to see the ocean coming alive because all of these things are popping up at the surface. It’s because things underneath the water are chasing them and they’re trying to get away by popping up. There’s also the idea of these very colorful, crazy things that the fish want to eat that are in the tackle box. And you’d never think that a fish would strike at a fluorescent pink flashy thing, but it does. It goes after it! Fishing itself, being out there at night, and watching everything in the water, is absolutely fascinating because I associate it with the subconscious. So everything that is underneath the water is part of the subconscious and, when there’s turbulence under the water, things pop up to the top. The water has always been a metaphor for me of the waking and the non-waking life, or the conscious and the subconscious meeting.

AL: How do you decide which idea to pursue? What’s the criteria, what’s that dialogue?

JR: I love process and I love technical puzzles. So if I’m pursuing an idea, there is usually some sort of engineering problem to solve with it. And then there’s some sort of technical process that taps into my depth of knowledge with ceramics that I find satisfying. So for example, I am really nerdy about glaze materials and chemicals, and I could talk forever about that. But I know enough to know what I don’t want to do, which is why I color the clay. I know that’s the best option for me. I think that the loom has so many possibilities because it’s a technical puzzle, and that’s really fun for me to solve.

AL: What gets you excited about the work?

JR: I’m excited about sitting in the studio and doing one thing over and over, [it’s] always very comforting to me, but then the ability to take this off of the loom — the moment when I cut it free and it becomes its own thing is kind of the part that I crave.

AL: Do you know what it’s going to look like?

JR: No, I don’t because it has such a rigid life when it’s on the loom or in construction. Then when I cut it free, then it starts to really speak to me about what his personality can do. Like the Tiny Monster Hungry. I had no idea that that piece would be able to twist and move and be so like… like a hedgehog. But it just looks like a hedgehog, or some other creature that’s unnameable. Those kinds of surprises are really gratifying to me. That’s why they’re so small! I can’t wait to get it off the loom and look at it.

AL: You talk about how they feel alive, or they’re kind of like these little creatures. When you describe [the process], it’s almost like they’re being born. So how did you decide to call them Tiny Monsters?

JR: I started to thinking of them as monsters during Covid because they began during the quarantine. I really liked that idea of them seeming so alive, but they are not anything that you can recognize as a living creature. The only other thing I was thinking of is “monster.” Monster has became the synonym for this living thing that we have no knowledge of.

AL: So “monster” strikes me as an interesting choice because it usually has a negative connotation. Monsters are quite often considered to be destructive.

JR: Well, these guys are super destructive. I see them as very mischievous. I see them as distrustful. They’re spiky. They’re not friendly to touch, and they’re really smug. When I’m making them, I’m attaching a lot of emotion to it and that emotion becomes its own living thing. Like this [one particular] monster I made: it’s so proud of itself. It’s fancier than the rest of them and it knows it. So, these are some personalities that I give them, and it’s projection, it’s all projection. When I created my most recent monster, I was thinking about my friend who recently died. I spent a lot of time in the studio weaving and crying. I haven’t named this one. I don’t think I could call it Grief because it doesn’t look like grief, but it definitely has some prickliness to it, and that’s appropriate for the emotion that I was putting into it as I was working.

The one that’s called Hungry — that one was sitting in the living room and I would work on it every once in a while, usually before dinner. So maybe I was hungry, but I hate to be that pedantic about it. But it does seem like there’s a certain emotion that goes into the pieces.

AL: As you were saying, you don’t know how they’re going to look off the loom — how they’re going to portray and attitude or interpret a personality.

JR: There’s still something that I have not been able to wrap my head around that’s so special with the weaving process. There’s a lot there and I don’t know that I’ve unpacked it all. All I know is that I haven’t stopped experimenting with it. So it’s ongoing. This is still a very experimental process for me. The work that [is in] the show — it’s a tip of the iceberg about what this medium can do.

AL: When we think about weaving — weaving is a historical process, and it’s an interesting pairing with other types of traditional processes, like ceramics. You’re literally creating the cloth.

JR: Right. And that cloth touches the body, right? I can make ceramic dishes and we can eat off of those. And that has its own intimacy, but it’s not part of you, it’s always an accessory — whereas the cloth is part of you.

‘Jen Rose: Since Last We Met’ is on view at CAMIBAart Gallery, Austin, April 15 – May 15, 2021