Note: On Video is a column in which film curator and arts organizer Peter Lucas points to a range of off-the-beaten-path videos that can be streamed online but might not otherwise get noticed.

The roughly hundred-year history of “visual music” films is an interesting and often overlooked one. I have a real love for the various synaesthetic works of artists who’ve experimented with making films not simply with music but as audiovisual music. Unfortunately, the films of many early pioneers such as Oskar Fischinger, Mary Ellen Bute, Jordan Belson, Harry Smith, and Hy Hirsh have not been widely screened and, aside from some poor-quality excerpts, are not available online.

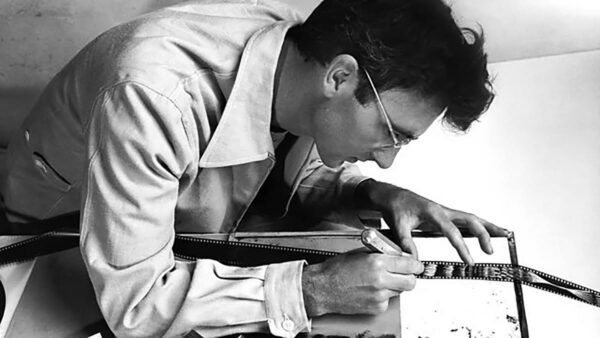

However, there are two great animation artists whose work between the 1930s and ‘70s is available to stream online: Norman McLaren (many films are available for free through the National Film Board of Canada’s website) and Len Lye (a program of eight short films is available for $4.99 on Vimeo). While different in approach, Lye and McLaren began filmmaking around the same time. They’re seen as the first artists to create “direct animation” films (drawing, painting, and scratching directly on film without use of a camera), and both were deeply interested in combining the disciplines of visual art and music to create new experiences of image, sound, and movement.

NORMAN MCLAREN

Scottish artist Norman McLaren began experimenting with moving-image art as a student at the Glasgow School of Art in the early 1930s. His dynamic student films using direct animation, pixilation effects, and superimpositions led him to a job with the film unit of the General Post Office (GPO) in London. At the outbreak of World War II, he left London for New York City, where he worked with experimental animator Mary Ellen Bute, and was also supported by a Guggenheim grant to make his own films. In 1941, he was invited to move to Canada and work for the National Film Board to create films and open an animation studio where he’d recruit and train animators. McLaren is most associated with the NFB, where he worked nearly continuously between the 1940s and ’80s, taking only a few brief departures for his work with UNESCO to teach animated filmmaking techniques in China and India.

While the NFB site offers free streaming of more than 50 short films by McLaren (and also a great deal of other experimental, documentary, and narrative films, by the way), I’ve highlighted here just a handful of favorite shorts to check out. These include a couple of his early, hand-drawn Jazz abstractions, and a couple of later films for which he animated not only the visuals but also the music, creating synthetic sound via shapes drawn directly on the film’s soundtrack.

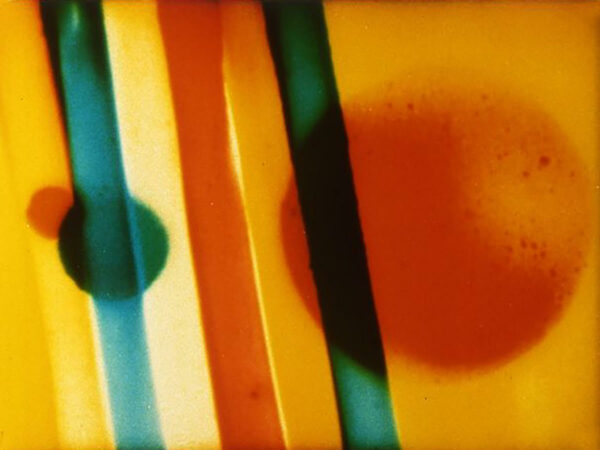

Begone Dull Care (1949, Norman McLaren, Evelyn Lambart, 7:50) View here.

McLaren and frequent collaborator Evelyn Lambart hand-painted lines, shapes, colors, and textural blends directly on the film strip to appear and move in time with the Jazz music of the Oscar Peterson Trio.

Boogie-Doodle (1941, Norman McLaren, 3 min.) View here.

An earlier direct animation, done while McLaren was living in New York — the “boogie” of the title by pianist Albert Ammons, the “doodle” drawn directly on the film stock by McLaren.

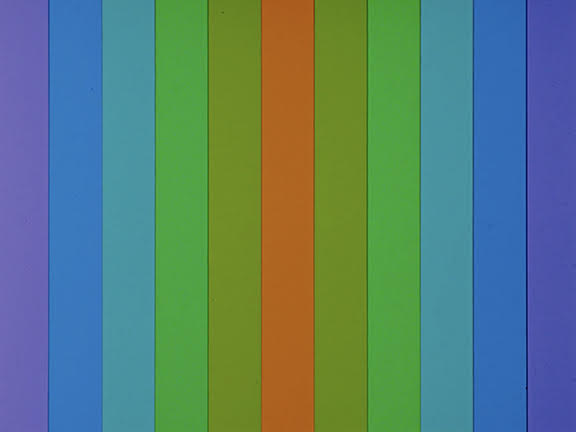

Mosaic (1965, Norman McLaren, Evelyn Lambart, 5 min.) View here.

A colorful, hypnotic mosaic of gradually unfolding and increasingly complex patterns in movement, color and sound. Remember that this and all of these are meticulously hand-made without aid of any computers or digital tools.

Synchromy (1971, Norman McLaren, 7:40) View here.

An amazing synchronization of image and sound, literally. As with Mosaic, McLaren composed the film’s music by visual shapes and patterns on the film’s actual track, and then moved those shapes to become part of the visuals, so that you see what you hear.

LEN LYE

New Zealand artist Len Lye had an early desire to portray movement and energy in his work, and in the 1920s began a life-long career of making experimental films and kinetic sculpture. “All of a sudden it hit me,” Lye recalled his early revelation, “if there was such a thing as composing music, there could be such a thing as composing motion.” Lye moved to London in 1926, where he was a part of the modernist artist group the Seven and Five Society, and began to experiment with drawing, painting, stenciling, and scratching directly onto celluloid. He did work with the GPO Film Unit (as Norman McLaren did), continuing avant-garde experimentation but working these techniques into various sponsored film projects. Lye moved to New York City in 1944, where he befriended and influenced many important American experimental filmmakers, painters, and writers. Lye lived and worked in the United States until 1968, when he returned to New Zealand.

French experimental film distributor RE:VOIR has made the program Len Lye: Rhythms, containing eight of his short films, available for paid streaming ($4.99 to rent, $11.99 to purchase) on Vimeo here. I’ve included some notes on the films as well as a trailer for the program below.

Kaleidoscope (1935, Len Lye, 4 min.)

Partly a cameraless abstract film, with imagery painted directly on celluloid and synchronized to Beguine d’Amour by Don Baretto and his Cuban Orchestra. Made as a theatrical commercial for Churchman’s cigarettes.

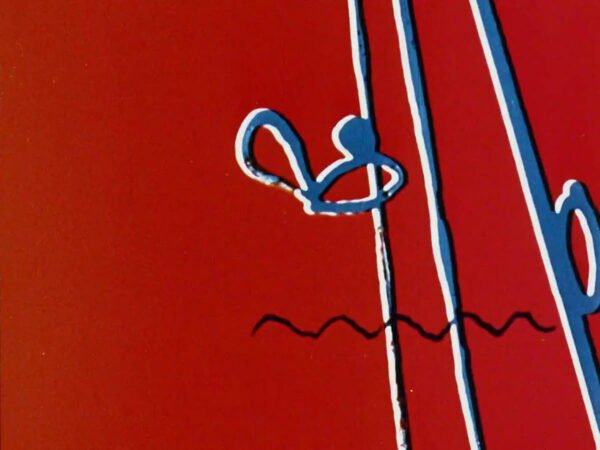

Colour Flight (1938, Len Lye, 4 min.)

A colorful film made for Imperial Airways featuring Lye’s hand-painted and stenciled bird imagery accompanied by the music of Red Nichols and his Five Pennies.

Swinging the Lambeth Walk (1939, Len Lye, 4 min.)

Lye’s direct film imagery with music. The “Lambeth Walk” was a popular dance with a characteristic hand gesture and call (“Oi!”).

Colour Cry (1953, Len Lye, 3 min.)

Made in the U.S., a direct film made by the ‘rayogram’ method, exposing the film with stencils, color gels, and objects on it and editing the results to Fox Hunt by blues musician Sonny Terry.

Rhythm (1957, Len Lye, 1 min.)

Invited to make a one-minute film for the Chrysler Corporation’s weekly television program, Lye took 90 minutes of car-factory footage and created this experimental montage set to African drum music.

Free Radicals (1958/1979, Len Lye, 4 min.)

A celebration of energy expressed by light and movement. Lye made scratches directly on black film leader using a variety of tools, from saw teeth to arrow heads. This dancing pattern of flashing lines and marks was cut to a soundtrack of African drum music.

Particles in Space (1967-1971/1979, Len Lye, 4 min.)

Synchronized to drum music from the Bahamas and Nigeria, the film begins and ends with sounds of Lye’s steel kinetic sculptures. Lye made several versions of this film in the late ’60s, but revised it in 1979.

Tal Farlow (1960/1980, Len Lye, 1:30)

Lye’s direct scratch patterns accompany the jazz guitar of Tal Farlow. Created in the late 1950s, and revised in 1980.

For last week’s series installment, on African-American actor and director Ivan Dixon and his involvement in two unique landmarks of independent cinema, please go here.