On Saturday, May 30th, in San Antonio and scores of other cities around the world there was a protest against racist police violence after the horrific murder of black Houston native George Floyd in Minneapolis on May 25th. George was a multi-talented and broadly liked man who been an excellent high school athlete (with Spurs legend Stephen Jackson) and had rapped on a DJ Screw track back in the ’90s. He was working at a club in Minneapolis and, like 40 million other Americans who were laid off during the Coronavirus and only received a pittance in government aid, was hard up. So he committed a “crime” in the same way Jean ValJean in Les Miserables committed a “crime”; he tried to pass off a counterfeit $20 bill (it is unclear if he even knew it was counterfeit). For that he was murdered by the white, dead-eyed genocidaire Derek Chauvin, who agonizingly asphyxiated Floyd for more than eight minutes, with a knee to Floyd’s neck and a banal expression of boredom, as if this was something he had done many times before.

As what happens with these periodic real-life snuff films of lynchings, the “authorities” willfully blew it. They dragged their feet in arrests; the county attorney Mike Freeman gave an infuriating press conference where he alluded to “other evidence.” We watched a man beg for his life as he was sadistically murdered. What other evidence was needed? A county autopsy report listed the cause of death as “underlying conditions and possible intoxicants” (two later autopsies would list asphyxia as the cause of death). It was clear they didn’t give a fuck. After Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Sandra Bland, Eric Garner, Walter Scott, Botham Jean, Breonna Taylor, and all the other unarmed black people murdered by the state, they still thought, in a democratic city in a blue state, that they could get away with it.

This time they didn’t. The people burned the 3rd precinct in Minneapolis, an act that had it occurred in a designated “evil empire” country like Iran or Venezuela would be celebrated as an act of freedom by the same scolding nerds condemning it now. In San Antonio, the protest in Travis Park and subsequent march was completely peaceful and enormously moving. “Say his name! George Floyd!” The crowd roared in honor of a person that the literal and (spiritual) heirs to slave patrols tried to erase completely. Later that night, things turned more confrontational. The brown shirts of MAGA America, an army of white men kitted out like tier-one operators in Zero Dark Thirty, guarded the cenotaph of the Alamo. Later on the police dispersed protestors with tear gas.

The media and various public voices clucked about riots and looting, but the extensive video evidence of cops driving into crowds, firing tear gas and rubber bullets into people’s eyes and necks at close range, attacking journalists, and shoving old peace activists, are convincing that these skirmishes should really be classified as police riots. In Louisville on June 1, the same police department that had just recently burst into Breonna Taylor’s apartment and rained bullets into her during a mistaken no-knock raid, killed another black man, David McAtee, who ran a restaurant and frequently fed law enforcement officers free of charge. A message is being sent. The cops aren’t going quietly; they are saying we have the power and we control what is the law. This is the result of 40 years of declining crime, and yet ballooning prison populations, exploding police budgets and buying sprees of military equipment, and a plethora of Turner Diaries-esque psychotic cop seminars.

The budget for police in San Antonio is over $500 million; for Houston it’s $956 million; Austin, $400 million; Los Angeles, $3 billion dollars. These all represent more than 30 percent of each city’s budget. And yet, national clearance rates for murder are only 59% percent; for other violent crimes 40% or less; property crimes under 20%. What are we paying for exactly? They’re showing us right now.

Since then, the classic Lenin quote “There are decades where nothing happens; and there are weeks where decades happen,” is apt. Attorney General of Minnesota Keith Ellison took over Floyd’s cause from the feckless Freeman, upping the charge to murder 2 and charging the glassy-eyed other officers/collaborators. The FBI opened the case of Breonna Taylor’s death; throughout the country schools and universities severed contracts with police departments; Minneapolis city council voted to disband the police, and municipalities began seriously discussing cutting funding for the police for the first time I can remember.

Meanwhile Trump, who increasingly resembles a honey-baked ham who is startled awake from a deep slumber and is furious, gassed protestors in D.C.’s Lafayette Square so he could waddle across and hold a bible up awkwardly, like a fat cop in an erotic thriller finding a VHS tape at a sex crime scene. On Juneteenth (June 19), a day that should be a national holiday of freedom, Trump was scheduled to hold his first post-Covid rally in Tulsa — on the 99th anniversary of a white race riot against Tulsa’s (now long-ago-destroyed) Black Wall Street. The white mob murdered more than 300 people then. The rally date has since been moved to June 20, but Trump’s original Juneteenth plan was a pretty clear dog whistle. In fact its frequencies are so understandable I think it can simply be called a “whistle”.

I don’t know what’s going to happen. It’s a new feeling — fear with some glimmer of the unknown, actual change like light diffusing off the bend of a mountain tunnel. So with this long but necessary preamble (I found I couldn’t blithely write about sauntering into a museum), I made my way to the San Antonio Museum of Art (SAMA) as it reopened to the public since its closure for the pandemic. SAMA kept it at 25% occupancy, so the experience was that of mostly wandering through an empty museum by yourself. Which is to say, it was basically heaven — a brief respite of serenity from this season of hell.

I was immediately drawn to the Egyptian wing of the museum. The older a piece of art is, the more silent and inscrutable it seems, on some elemental level. The canopic jars from 3000 years ago are described by the wall text:

“These jars held the internal organs of a man named Pef-abekh-neith. During the mummification process, embalmers removed the organs from the body and stored them in canopic jars for placement in the tomb. The jars’ lids represent the Four Sons of Horus, gods who protected the organs. Falcon-headed Qebehsenuf watched over the intestines, jackal-headed Duamutef protected the stomach, human-headed Imsety guarded the liver, and baboon-headed Hapi had charge of the lungs.”

Beyond that straight-forward description is the unsettling blank smile of eternity. I thought of the epigraph of Barry Lyndon: “It was in the reign of George III that the aforesaid personages lived and quarreled; good or bad, handsome or ugly, rich or poor, they are all equal now.”

It is also easy with such relics of antiquity to fall into a rabbit hole, wondering about their source. These were purchased in 1927 by the Stark family, who made a fortune in lumber in east Texas. From whom did they buy it? From whom did the seller to the Stark family buy it? At a certain point back, most of these objects passed through the hands of a “looter.” The word loot comes from the Hindi (and before that Sanskrit) word lut, meaning “goods taken from an enemy.” This was certainly a useful word for the British as they sauntered through the Indian sub-continent, filling the British Museum in their wake.

Walking through the Egyptian wing the day after the police tear-gassed people around the Alamo, I thought of the Rabaa massacre in Egypt in 2013, and how quickly it has disappeared from cultural memory. General Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, current military dictator of Egypt, ordered his troops to wantonly murder more than one thousand civilians, mainly members of the Muslim Brotherhood. Sisi has only prospered since then, controlling Egypt with an iron fist, receiving billions in U.S. aid, and being received by the sweating jack-o-lantern rictus of Trump at the White House just last year. I imagine that the people who thrill to the cops firing tear gas and rubber bullets at protestors would be unperturbed by the Rabaa massacre. After all, it killed members of an evil “terrorist” organization, the Muslim Brotherhood — right? It is not hard to see the car dealership owners, the pool-repair barons, and the tanned, flaking residents of the Villages muttering to themselves, “They oughta do that over here.”

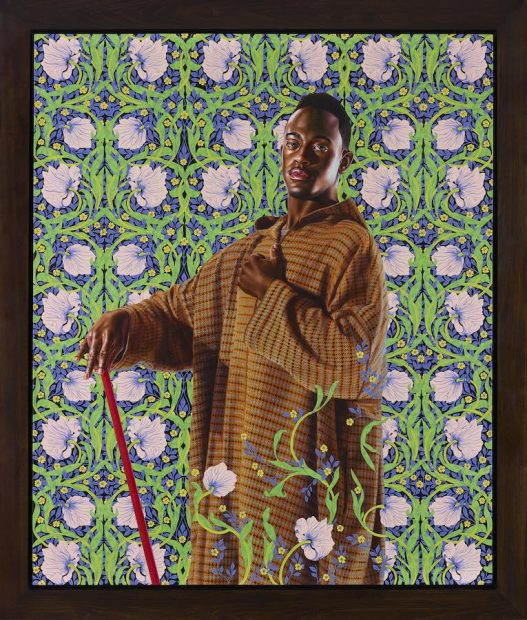

I made my way to the Contemporary wing and was immediately struck by Kehinde Wiley’s self-portrait/reclamation of the famous Thomas Lawrence portrait of David Lyon. Lyon, a West Indies merchant (quite a sinister phrase, like “German émigré in Argentina”) from the 19th century, was a very wealthy man and upon the abolition of slavery in Jamaica, he was compensated for the more than 2,000 people he enslaved (as were the ancestral family of David Cameron). In the Lawrence portrait, Lyon is resplendent in fur with a polished cane. His scale is purposefully out of proportion; he looms like a giant striding over the globe. The luxury of dominion. In contrast, Wiley’s version is at ease and intertwined with his surroundings; behind the meditative calm of Wiley’s expression (in contrast to Lyon’s smirk drifting toward the waterfall of a scowl) is the frisson of ecstatic release — an old colonial symbol broken or reclaimed.

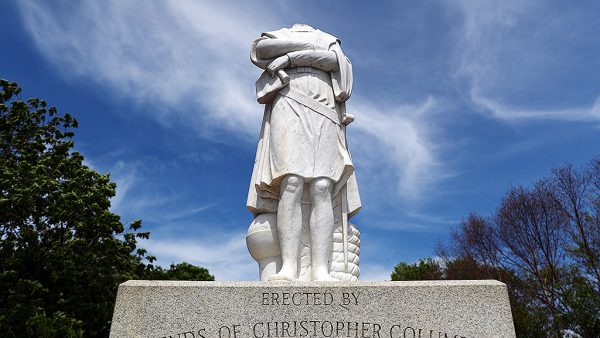

This frisson has thundered across the globe in the last few weeks in the greatest and most righteous performance art I have ever seen. Slave trader Edward Colston’s (1/5 of those enslaved on his ships died) statue yanked down in Bristol and dragged through the docks and thrown in the same water his ships used to anchor in; Robert Milligan, another West Indies merchant, who built the West India Docks, infuriated that his rum and sugar and coffee shipments from slave labor in the Caribbean kept getting stolen, was removed by the government in London; one Columbus statue pulled down and into a lake, another beheaded; Robert E. Lee pulled down or covered with coat after coat of bright paint and denouncements; King Leopold II, perhaps the purest white devil of all time, toppled in Brussels; Jefferson Davis, president of a would-be slave empire that violently attacked the United States, pulled down with rope.

All these statues have the same beatific serenity of the gods on the canopic jars, but in life these were perpetually scowling men. Scowling at lost profits, lost property; scowling at perceived slights from their underlings, those in their families, those they employed, and those they enslaved. Scowling as they ordered hands hacked off, lye put into the lash wounds of the enslaved, children raped, bodies dropped into the sea. That these statues have remained for so long, casting long shadows throughout the afternoon year after year, is illustrative of the resilience of their dominion. Most of them died relatively old, well-fed, in peace. They are lucky that they reside in the morass of oblivion and cannot be pulled by the ankle or throat, naked and screaming from Hades, to face trial.

The artist Philip Guston’s last and most righteously brilliant phase was prefaced by a personal (and highly relatable) crisis:

“So when the 1960s came along I was feeling split,

schizophrenic. The war, what was happening in America,

the brutality of the world. What kind of man am I,

sitting at home, reading magazines, going into a frustrated

fury about everything — and then going into my studio to

adjust a red to a blue.”

His humid works of Klansmen crammed into little Klan cars have never seemed more relevant and alive. They appear like claymation, ready to drive off the canvas to join a group of heavy-breathing patriots in the armed protection of a suburban GameStop. Until the day I wandered the reopened SAMA, I had never seen his 1976 (the bicentennial of America) piece Ocean, which uses the same gory viscera of his Klan works. This ocean is blood red with a ribbon of turquoise reef and algae — it is the Red Sea, in desperate need of parting. A swell of blood, the water off the Gulf coast, viscous, red tides blooming, temperatures rising, hurricanes rolling off the production line like cinnamon rolls. Which is all to say: It sure feels like another “hottest year ever,” and the hurricanes haven’t started yet.

The waves in Ocean resemble slabs of meat and strike at one facet of Guston’s genius — his unsettling spatial intemporality. The textures in his work have a vestigial relation — as if each discrete shape or object could become an appendage of another. This is Guston’s quantum theory of unity, the body horror of connectedness. The same body horror of a virus looping the globe free and easy, like the eye of a hurricane, with all the time in the world.

The other major collecting museum in San Antonio, the McNay, was scheduled to clear out its entire permanent collection to host the titanic, history-shaking exhibition Vida Americana (traveling from the Whitney) starting this month. I had planned an entire trip to New York just to see this show, and was overjoyed it was coming to Texas. The plans for this are understandably up in the air, as the show will remain in New York for some time. Vida Americana chronicles the incendiary, vital works of Mexican painters from 1925-1945, including José Clemente Orozco, Diego Rivera, and David Alfaro Siqueiros. These artists, coming out of the rocket ash of revolution, the ten-year period between 1910 and 1920, captured in their murals and portraits the urgency of everything. The socially real was psychological and vice versa. The murals chronicle the sweep of life, with its rapacity and genius, and form lattices of geometric abstractions from a distance.

David Alfaro Siqueiros’ El Grito (The Scream), on view at SAMA, is more classical in style than his giant, strident murals that appear as neon-lit panels in the grand comic of cruelty. Siqueiros’ life included fighting in the revolution, teaching Jackson Pollock some painting methods, and attempting to assassinate Leo Trotsky. (He was a Stalanist.) In El Grito, he takes pre-Colombian sculptural forms and casts them as the anguish of eternity in the oppressed. Whereas Munch’s Der Schrei der Natur (The Scream of Nature) is a Herzogian howl of chaos and insignificance, El Grito is The Scream of Humans. And it is always an unsettling scream, then and now, but imagine if one day the screams ended and there was just silence.

That night, after the museum visit, I watched John Cassavetes 1977 film Opening Night. Cassavetes is not really a “political” filmmaker, since his films are so deeply personal and emotional, concerning the life and struggles of white Silent Generation people and their various stages of functioning (or not) alcoholism. But in this moment, Opening Night struck me as an almost universal metaphor of struggle. In the film, Gena Rowlands plays famous actress Myrtle Gordon, who is in rehearsals for a new Broadway play. One night she is approached by an adoring 17-year-old female fan who reminds her of youth. The girl immediately dies in an auto accident that Myrtle witnesses, and it sends her completely adrift, Dante-like, in the middle of her life. She is literally haunted by the girl, berated by the older playwright, drenched in despair, dread, and panic. On opening night, Myrtle arrives dead drunk. A stagehand remarks, “You really are something. I’ve never seen someone so drunk be able to stand.” Myrtle muddles through the first two acts, but in the finale breaks through, goes off script, and enters into a deeply funny and soulful improvisation. She triumphs by standing up for herself, and walking through the open window of the unknown.

Being wasted on opening night is a pretty brutal and incisive metaphor, as is being unsure if you are able to stand. Some haven’t been able to stand because they’ve had a boot on their necks for years, generations, centuries; some don’t stand because they rut and frolic in the bullshit of the past, its myths, its brutal hierarchies. And some like me, and those who look like me and grew up like me (like Diane Sands says about her mixed-race child-to-be with Beau Bridges in Hal Ashby’s underrated The Landlord, “I want the boy to grow up white — casual”) I’ve never really stood because I’ve never really had to, ferried around on a divan chair built by materials from the Colstons and Milligans of the world, passing through life like Buddha passes through the city strategically purged of suffering.

In the script of the last act, Myrtle is supposed to get slapped and fall weeping. The director of the play (Ben Gazzara) says: “You’re a woman; you need to get hit to be sympathetic.” The people, like Myrtle, are tired of sympathy, and don’t want to be hit anymore. They have decided to go off script.

1 comment

Beautifully written. Thank you.