When looking at photographs from 70 years ago, it’s easy to wax historical, especially if the images are black-and-white photographs of African-Americans. Gordon Parks: The New Tide, Early Work 1940–1950, a current exhibition at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth, includes more than 160 prints in all, and it flows like a series of historical documents from part of our learned history. Or the history that we almost learned. There is also no avoiding the occasional reverie for what Parks’ images illicit in his viewers: the space between the war years and the beginning of the ’60s Civil Rights Era.

We have seen Eyes on the Prize, or should know the Emmitt Till story, and we will undoubtedly revisit all of this in February, a.k.a. Black Mystery Month, when it is fashionable to elevate the Black American experience to any level of significance. While these images are indeed snatched from history, they are also worth revisiting from where we stand today.

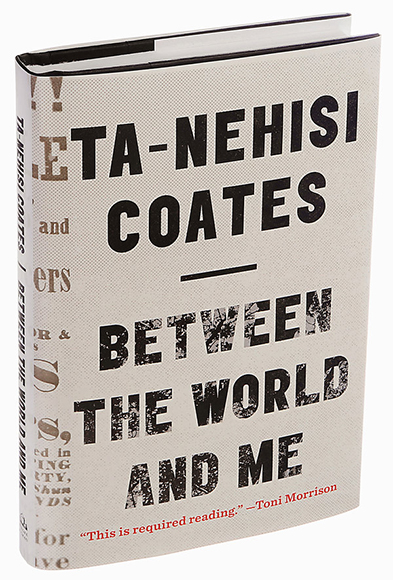

Ta-Nehisi Coates’ essay memoir Between The World And Me was a recent Amon Carter Museum book club selection that I connected to an exhibition tour I was asked to lead for the museum (in my other role as a visual artist). My tour touched on where Coates’ book and Parks’ photographs intersect, and although generations apart, Parks’ and Coates’ outputs read as a parallel history. Parks’ photographs illustrate many of the themes in Coates’ novel, and the exhibition title alone has a certain hopefulness that points to deliverance and transcendence in the years before the Civil Rights movement. Even before our current political moment, most of that hope had faded — Jesse Jackson’s “Keep Hope Alive” and Obama’s “Hope” campaign notwithstanding.

Washington, D.C. Government charwoman

Gordon Parks (1912 – 2006)Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Photograph. Courtesy of and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation

One of Parks’ photographs, Washington, D.C. Government charwoman, a portrait of Ella Watson, is blown up to wall-size at the entrance of New Tide. The image immediately clashes with any dream of America that, as Coates puts it, “Is Memorial Day cookouts, block associations, and driveways … treehouses and the Cub Scouts … smells like peppermint but taste like strawberry shortcake.”

Watson, the subject of “American Gothic” (as the photograph was renamed for Parks’ exhibitions), worked in the offices of the Farm Security Administration (FSA), where Parks landed after some creative advocacy from the father of the Harlem Renaissance, author Alain Locke (The New Negro). With the help of Locke and others, Parks received a fellowship grant from the Julius Rosenwald foundation to work with the FSA under Roy Stryker. It was Stryker’s admonition for Parks to first work without a camera (he actually asked for the camera, and then placed it in a closet for two weeks), that led to the eventual photographs of Watson. Stryker encouraged the young Parks to look at people closest to him and his immediate surroundings.

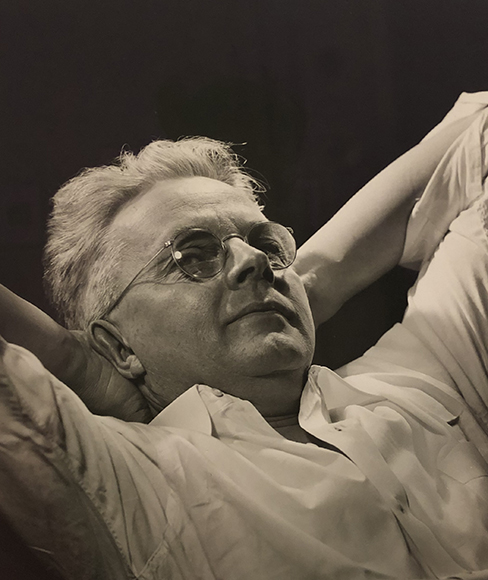

Roy Emerson Stryker ca. 1947. Gelatin silver Print. National gallery of art, Washington, Corcoran Collection (The Gordon Parks Collection. Courtesy of and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation

A 26-year government employee, Watson worked from 5:30 P.M. to 2:30 A.M., cleaning offices, halls, and toilets, and took care of a household of three grandchildren and a adopted daughter on her $1,080 annual salary. Posed in front of the America flag with a broom in her right hand and a mop in her left, Watson stands both as the literal poster child of hard work and dedication, and the refutation of the idea that the means of achieving the American Dream is through hard labor alone. This is the first salvo from Parks’ “choice of weapons,” as he described the camera as a tool to fight the racism and injustices that faced him and his generation.

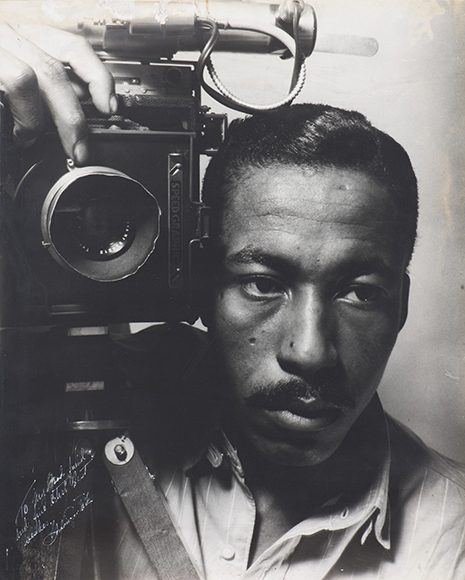

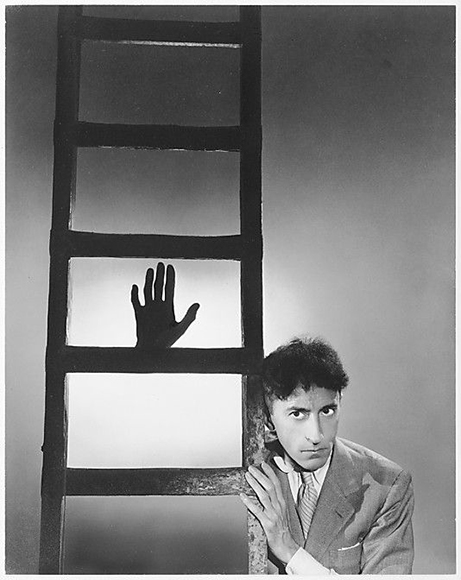

Gordon Parks

American, 1912- 2006

Self-Portrait, 1941.Courtesy of and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation

Private Collection.

From Minneapolis to Chicago, Harlem to D.C. and beyond, the self-taught Parks evolved from a photographer who was influenced by his contemporaries — masters of the craft he was determined to wield — into his own man and artist, navigating assignments to bring stylized portraits of his community to light.

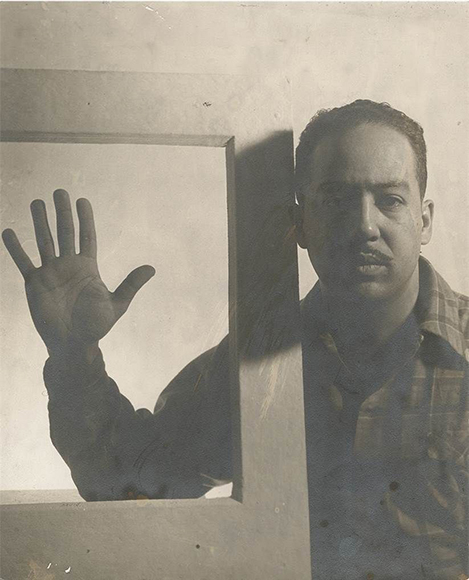

Langston Hughes, Chicago. December, 1941. Courtesy of and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation.

Parks’ image of Langston Hughes, for example, is undoubtedly influenced by Surrealist and Dada artist Man Ray, as well as George Platt Lynes’ photograph of Jean Cocteau from 1936.

George Platt Lynes’ photograph of Jean Cocteau from 1936

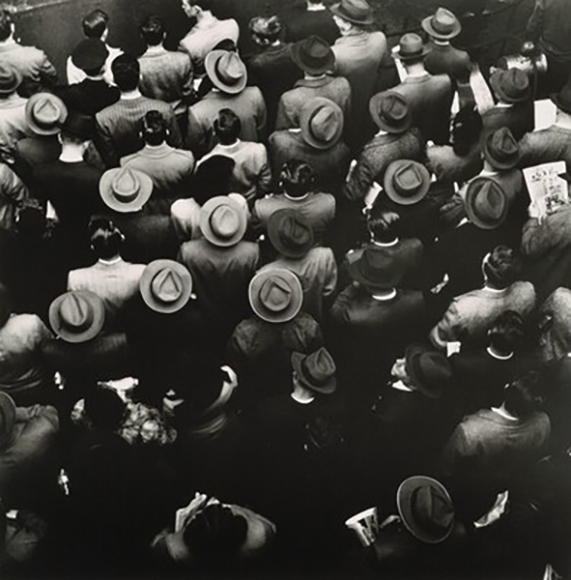

In another Parks’ photograph, Ferry boat from Staten Island to Manhattan, carrying early morning commuters, New York Harbor, there are traces of Alfred Stieglitz’ Steerage photograph from 1907.

Gordon Parks, Ferry boat from Staten Island to Manhattan, carrying early morning commuters, New York Harbor. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Photograph.

Parks, then a burgeoning photographer encouraged to learn from the giants of the medium, looks to be influenced by their works. On the same wall as Ferry Boat is Coal Sketcher, his photograph of a coal worker shot in high contrast that pops forward the subject from the dark background that frames his labor-defined face. It evokes the famous photographs of Lewis Hine, whose photographs of industry and child labor, shot in the very factories that exploited children, led to fundamental changes in this country’s child labor laws.

Coal Sketcher, Harlem River, New York, 1946. Gordon Parks (1912 – 2006)Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Photograph. Courtesy of and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation

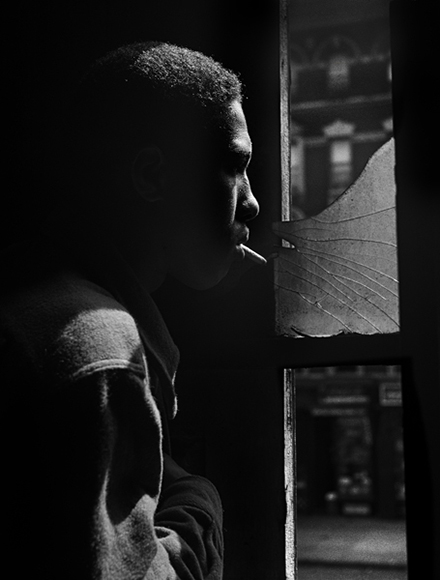

Harnessing these influences for his own work, from his time at the South Side Community Center through his first assignment at Life Magazine, Parks’ early portraits of his varied subjects reflect the awareness, empathy and confidence that defines his work throughout his career. Nowhere is that more evident than his 1948 photo essay focused on the life of Red Jackson, leader of a Harlem gang The Midtowners.

Red Jackson, Harlem 1948. Gordon Parks (1912 – 2006)Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Photograph. Courtesy of and copyright The Gordon Parks Foundation

The striking and melancholic composition that anchors the Red Jackson series is an image of Parks’ subject peering out of a broken window. According to Parks’ biography, Jackson and his cohorts had arrived moments earlier, running from a rival gang with Parks and his camera in tow, and they holed up in an abandoned building where Jackson busted out a window pane for a clearer view of the street.

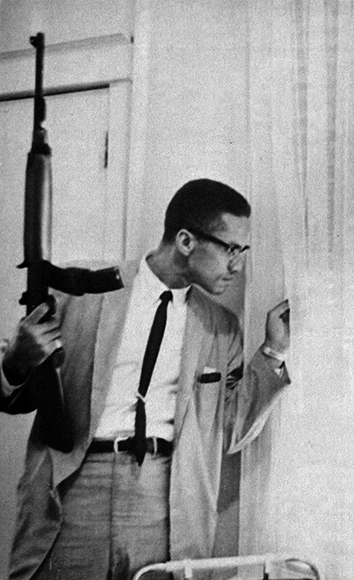

Photograph of Malcom X by photographer Don Hogan Charles, 1964.

In Parks’ portrait of Red, we also see Malcom by the window in the iconic Don Hogan Charles photograph, Martin on the balcony, and maybe even Coltrane on the cover of A Love Supreme. Red Jackson looks out in profile, as if to a future full of promise, but wears the furrowed brow of futility, as though accepting his fate and that of his peers. All at once he is trying to protect himself while looking to a future that offers only a skewed vision from a broken window.

Caught in a similar moment, Coates as a young writer was confronted by a boy with a gun who threatened to shoot at him and his friends. Coates’ recounts the story to reveal how the rules for him were different from the other world of kids whose only worry, it seemed, was poison oak. In a book passage that reads like what I imagine Red’s thoughts to be, Coates writes about the rules of the street and the urgency to learn those rules in order to navigate those streets, before he even learned his colors and shapes:

“To survive the neighborhoods and shield my body, I had learned another language consisting of a basic complement of head nods and handshakes. I memorized a list of prohibited blocks. I learned the smell and feel of fighting weather. And I learned that ‘Shorty, can I see your bike?’ was never a sincere question, and ‘Yo, you was messing with my cousin’ was neither an earnest accusation nor a misunderstanding of the facts. These were the summonses that you answered with your left foot forward, your right foot back, your hands guarding your face, one slightly lower than the other, cocked like a hammer.”

This is the lens and the story of New Tide: that we all live in the same country, but our experiences couldn’t be more different. In showing the world the Ella Watsons and the Red Jacksons whose lives are lived invisibly, and in images that normalize the beauty, intellect, and heroism of his subjects, Parks’ New Tide washes ashore some of the things our history tries to keep buried at sea.

Through Dec. 29, 2019 at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth

1 comment

Had the pleasure of meeting Gordon Parks and speaking with him while working on a small cable show, The Photographer’s Eye with Pete Turner. He was as gracious as he was talented.