Installation view of part one of ‘Roni Horn: When I Breathe I Draw’ at the Menil Drawing Institute, the Menil Collection, Houston, 2019. Photo by Paul Hester

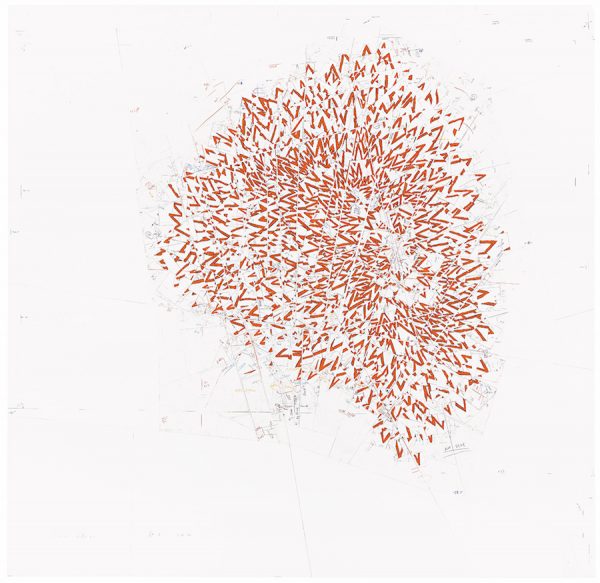

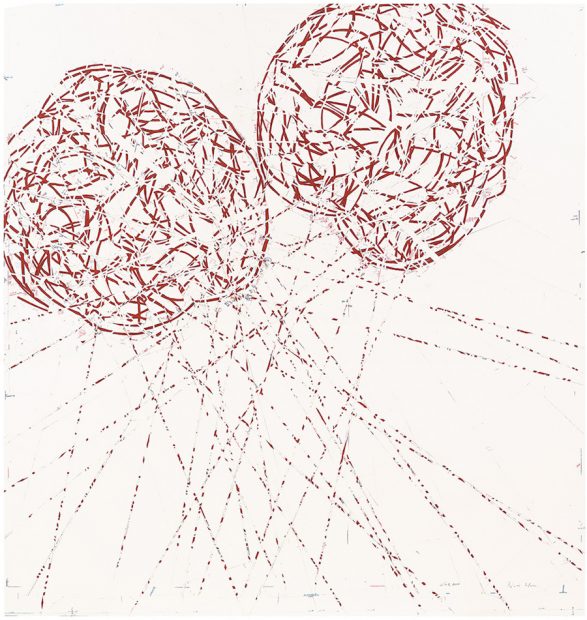

Currently, when you enter the main, dimly lit gallery of the still-new Menil Drawing Institute in Houston, you’re confronted by ten Roni Horn drawings that loom over you like majestic porcupines: jagged, staggered, tectonic. Your eyes engage with lines that dance between representation and abstraction, and with sculptural choices that leave pigment fuzzily resting atop the paper. We consider these drawings, initially, for what they seem to be: a play between two-dimensional formalism and three-dimensional materiality.

But, given that the works’ titles are all singular words that are parts of common speech — a verb, preposition, adverb, or conjunction (If, Or, etc.) — it could be more productive to consider these works for what they actually are, which are language drawings.

Roni Horn, If 2, 2011. Pigment, varnish, colored pencil, graphite pencil on paper. 101 9/16 x 101 15/16 inches. La Colección Jumex, Mexico.

The drawings are in fact populated with words. A lot of them. Horn has coined them “registration marks” or “background noise.” I think that we’re therefore supposed to deem the language populating the drawings as either a mechanism for Horn to make formalistic choices, or simply evidence of her hand — evidence of a moment that she intuitively (offhandedly) decided to leave on the paper. We’re meant to believe (I think) that the role of language in these works is subsidiary to image.

My skepticism of this position stems from three things: Horn’s previous history of (agreeable if not cheerful) evasiveness and winking subtlety; the relational use of language in all of these titles; and the exhibition’s pairing with a Horn work titled Wits’ End Sampler in the building’s foyer.

Horn has made her mark on the art world with sculptures that are deceptively simple, and infused with quiet, nearly inaudible drama. A frequent modus operandi of hers is twinning, and in that duplication, she dispels with the need (the viewers’ and perhaps her own) to emphasize or esteem one thing over another. Which makes me ask, where these drawings are concerned: Does the word “background” in Horn’s description of her use of language here as “background noise” really indicate an auxiliary purpose? Simply because the words are more difficult to see and apparently function as an apparatus to create the drawing, as opposed to being the drawing, doesn’t mean their weight is diminished. Given Horn’s impulse to duplicate, I’d guess that she intends the graphite words and the other aspects of the drawing (the powdered pigment, the colored pencil, the varnish, the topographic marks) to carry the same weight. Otherwise, why not just erase the words?

Roni Horn, Or 6, 2013-2014. Powdered pigment, graphite, charcoal, colored pencil, and varnish on paper. 107 ½ x 102 inches. Photo: Tom Powel Imaging.

Collection: Glenstone

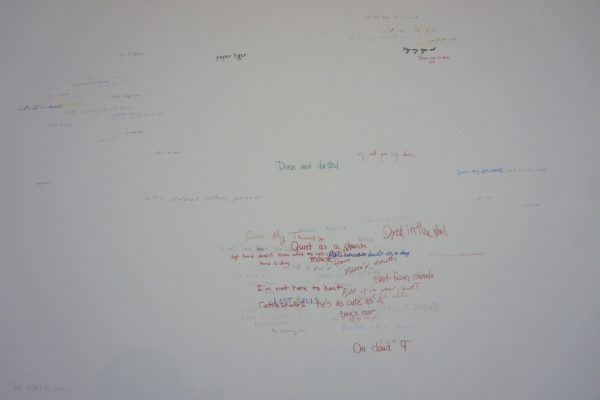

What Horn is doing with her titles is asking us to consider these drawings as two overlapping components that act upon or engage with each other. The titles give us this clue by being the type of words in a sentence that link two ideas together. Sure, you could argue that the two parts are simply line and materiality. But when you consider the ten drawings in the main space in conjunction with Wits’ End Sampler in the lobby — made up of silkscreened idioms that look directly hand-scrawled onto a wall, and seems to be truly about language — that line of thinking loses ground. Image and language are the two bookends to the open-ended sentences Horn keeps writing here.

Knowing that these drawings were originally created in the late ‘00s to early ‘10s, and that Wits’ End Sampler was completed in 2018, it’s not a far cry to read the solo show in the gallery as studies (playfully, at least) for Wits’ End. If that’s the case, it seems to me that Horn has let go of the delineation between language and image — and the dance between subtlety and preeminence — in favor of letting language become image.

On view at the Menil Drawing Institute, Houston, through May 5, 2019

1 comment

I’m surprised that this review doesn’t dig a little deeper into the breadth of what these drawings has to offer. I found these pieces to be both heroic and intimate with the image taking precedent. The little bits of text you’re referring to were a nice counterbalance to the commanding scale of the pieces. Also, the way they were made, woven together (obviously by hand) using the text and everything else in such a personal manner created something that felt like a different weapon in this artist’s arsenal. Many of the shapes nodded at the celestial as well as geometry, typography and humor. There are so many things you could’ve touched on describing these rich pieces.