The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston recently acquired a marvelous drawing of a steeple for the Rouen Cathedral. Attributed to the master mason of the building, Roulland le Roux, it was made sometime in the first couple of decades of the 16th century.

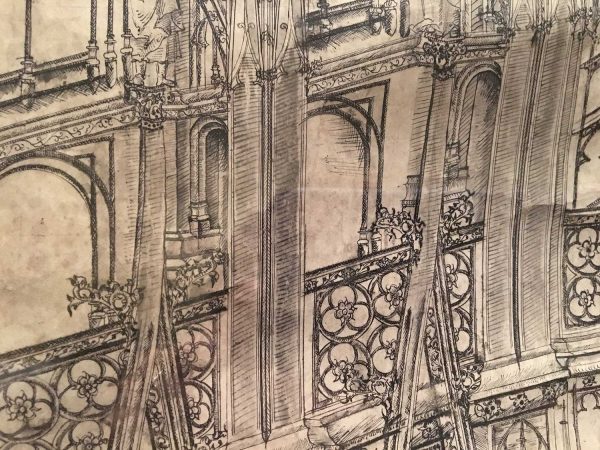

At 11 feet tall and not quite two feet wide, the drawing is monumental and imposing from a distance. Close up, it’s intricate, fanciful, and utterly charming. Statues of saints face each other, startled and interrupted in the midst of conversation. Gargoyles peer impishly around corners. Stone filigree recedes into sturdy columns, which recede into arches that suggest passageways beyond. It’s made on parchment, which gives it a velvety, rumpled surface and lends the edges a pleasing roughness. This is humanity reaching for the heavens, riding on the coattails of some long-dead animal’s skin.

This drawing was made at the turn of the 16th century, when France was in transition (in 2011, the Grand Palais in Paris dedicated an exhibition to the period). Renaissance humanist ideas were taking root and Medieval notions of piety and class structure being upended. Wars of expansion were being pursued into the weaker city-states of Italy. And the rumblings of religious conflict were being felt — a conflict that would explode into the terrible religious wars between Protestants and Catholics that would tear France apart in the latter part of the 16th century.

In short: France was on the cusp of seeing millions of people die over religion.

The wall text suggests that this drawing would not have been a builder’s plan, but would have been used as a sales tool for approaching prospective donors. If you built it, presumably, He would come.

The steeple was built and lasted until 1822, when it was destroyed by lightning. The replacement, which still exists today, is the tallest church spire in France.

And of course, the Rouen Cathedral’s facade was a favorite subject of Claude Monet.