Henri Huet, French (1927–1971), The body of an American paratrooper killed in action in the jungle near the Cambodian border is raised up to an evacuation helicopter, Vietnam, 1966, gelatin silver print (printed 2004), the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, museum purchase. © Associated Press

Draped in camouflage, bunting, or shroud, war’s singular product is death. In face after face of WAR/PHOTOGRAPHY: Images of Armed Conflict and Its Aftermath at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, nothing is more abundantly clear than the awful intimacy of war and death. The exhibition begs the question, is our greatest modern efficiency murder?

Anne Wilkes Tucker, Will Michels and Natalie Zelt have brought war home in 500 prints and objects spanning the era of photographed wars, from mid-19th century to the present. They have created an impeccably aligned maze of war’s miseries on the mezzanine of the MFA’s grand Upper Brown Gallery. Their great success might shock some viewers or lead them to new thinking about war. The assemblage is a staggering homage to the source of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, and while viewers are at little risk of acquiring the syndrome, veterans are advised to take their pills before they go. And they can go for free.

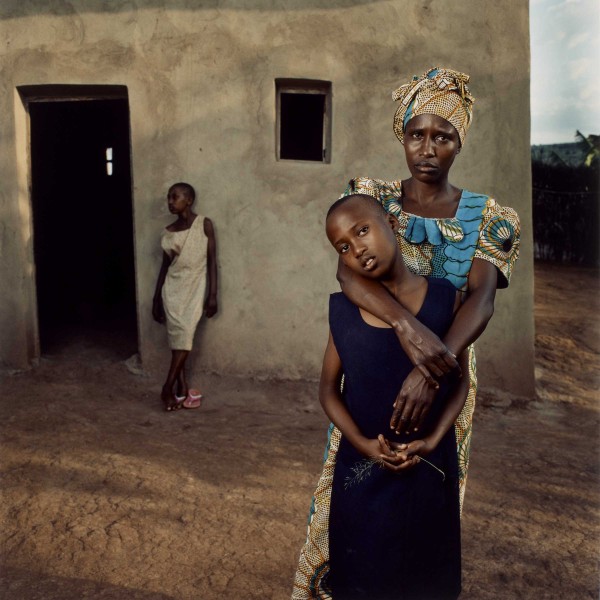

Walter Astrada, Argentinean (born 1974), Congolese women fleeing to Goma, from the series “Violence against women in Congo, Rape as weapon of war in DRC, 2008,” chromogenic print (printed 2010), the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, museum purchase with funds provided by Photo Forum 2010. © Walter Astrada

These war images are presented in an ahistorical arrangement by the developmental phases of each and every war. From provocation to recruitment and training, through the stages of waiting, faith and leisure and then into combat and on to retribution and memorializing, classic icons of the genre mingle with thematically similar but lesser-known photographs from earlier and later conflicts. Besides de-fanging those over-coded classics, the exhibition insists that viewers think about the nature of war beyond any sort of “Forrest Gump” sentimentality or the arrogant posturing of “The Green Berets.”

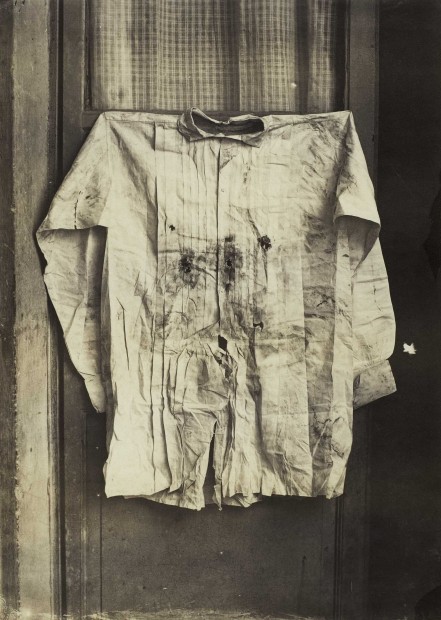

Francois Aubert, French (1829–1906), The Shirt of the Emperor, Worn during His Execution, Mexico, 1867, albumen print from glass negative, Lent by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gilman Collection, Gift of the Howard Gilman Foundation, 2005. © The Metropolitan Museum of Art / Art Resource, NY

The beginning confronts visitors with four large color prints of the second plane flying into the second World Trade Center tower. These grim reminders are surrounded by a collection of early photo equipment amidst a mélange of historical images that reference the onsets of several earlier wars, among them photographs of Abolitionist John Brown, the sunken USS Maine and Hitler triumphant at Nuremberg. There’s an early Sunday morning aerial photo of battleship row at Pearl Harbor as Japanese submarines initiate the attack, US soldiers departing for Afghanistan pausing to kiss spouses (with one man’s M-16 resting on the ground haphazardly aimed at his toddlers), the infamous deck of Iraqi playing cards with Saddam as ace of spades and a stereopticon of French soldiers at Verdun. An image of the equipment of the first war photographer Roger Fenton shows just how cumbersome it was to document the carnage. The only irony on the entire bill is an image of a hand holding a messenger pigeon emerging from a World War I tank. Though the pigeon resembles a dove, the emerging hand becomes a feeble gesture.

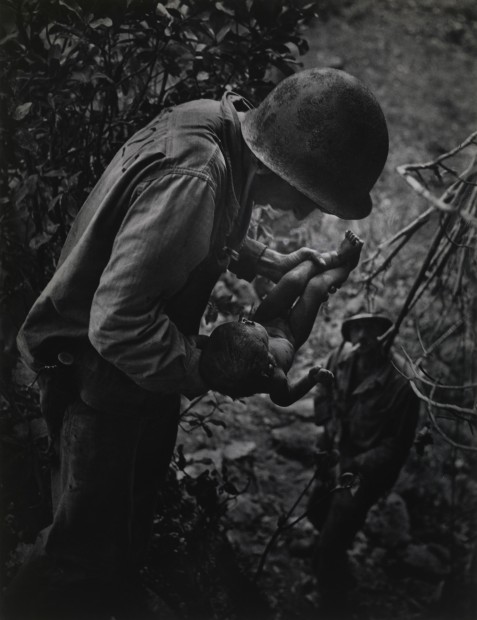

Philip Jones Griffiths, Welsh (1936–2008), Called ‘Little Tiger’ for killing two ‘Vietcong women cadre’—his mother and teacher, it was rumored, Vietnam, 1968, gelatin silver print, the Philip Jones Griffiths Foundation, courtesy of Howard Greenberg Gallery. © Philip Jones Griffiths / Magnum Photos

Because the exhibition extensively examines the relationship between war and photography, it is truly a vast portrait show. It has to be. War is a people business. There is beauty dressed in the brutal. A Taureg warrior, a shell shocked captain, a maimed female soldier, a nine-year-old “little tiger,” plenty of stunned and hungry civilians, skeletal death-camp faces and, in a huge color print, a young Taliban lying in a ditch that brings America’s current enemy into a sharply human focus on what we all have in common when we die unnaturally. So mostly, the faces of the dead haunt the hall, although there are also damaged children, civilians and soldiers plus devastated landscapes to reinforce the idea that photography bears bad news very well. “Q: And babies? A: And babies.” Perhaps war’s second product is photographs.

W. Eugene Smith, American (1918–1978), Dying Infant Found by American Soldiers in Saipan, June 1944, gelatin silver print, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, gift of Will Michels in honor of Anne Wilkes Tucker. © Estate of W. Eugene Smith / Black Star

Multinational and non-chronological, there are photographs from Russia, Mexico, Germany, Japan, Bosnia, Sudan, Afghanistan, Belgium, Vietnam—the list goes on and on—taken by a range of photographers both famous and not so famous. Though early on, it ceases to matter if the shot is a Rosenthal, or An-My Le, or Smith, or Nachtwey or Huet or Page or Filo or Ut or Duncan or Capa or McCullin or Steichen. There is a nook for Joe Rosenthal’s Iwo Jima flag raising and its various permutations from comic book to propaganda advertising the purchase of war bonds. But even that monster image becomes another frame from another war, its grit and grime and blood, its pain and finally, once more, death. In an odd way for me, being American also ceased to matter. Although I am a combat veteran, and love Texas as much as any other monkey, I ached in a deeply human fashion as I thought of my own friends lost in Vietnam, but also of that young Taliban dead in a ditch who made it all seem so furiously stupid, so pitifully human. And that may be the primary reason to attend this show: to see and understand what nations truly ask of their young men and women. You may need to revisit this exhibition.

Susan Meiselas, American (born 1948), Muchachos Await Counter Attack by the National Guard, Matagalpa, Nicaragua, 1978, chromogenic print (printed 2006), the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, museum purchase with funds provided by Photo Forum 2006. © Susan Meiselas / Magnum Photos

Transcending the mythic proportions given war by “neo-con” warrior cults and religious fanatics; transcending the prevalent American viewing stances as spectator, witness, or voyeur; transcending those notions of photographs as a window or mirror or altar; the exhibition repositions its viewers to gaze into the heart of war as if waking from a dream of peace. America, currently overwhelmed economically, politically, socially and spiritually by war, lives in its myths and romance, or most of us do, insulated from war’s devastating results. But the photo of Marines aboard an aircraft carrier at target practice as they check the paper human silhouettes, even as their bodies cover and become, metaphorically, those targets, is an apt symbol to this exhibition. This image brings it home: We are all targets in the media that brings us to combat. War/Photography pierces the veil and lays out the damage done in a depth and breadth not previously achieved. There is no stepping around the mess on the floor, no skirting the issue with the rhetoric of patriotism (and it should make viewers highly suspicious of politicians who attempt that maneuver) and no backing into “our glorious past” for shelter. Shorn of noble duty and blood sacrifice, this show provides much needed acknowledgement of our war debts and cherished myths, to proffer salvation as the painful understanding about the nature of combat, its costs and consequences.

Joe Rosenthal, American (1911–2006), Over the Top—American Troops Move onto the Beach at Iwo Jima, February 19, 1945, gelatin silver print with applied ink (printed February 23, 1945), the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, gift of Richard S. and Dodie Otey Jackson in honor of Ira J. Jackson, M.D., and his service in the Pacific Theater during World War II. © Associated Press

At the end of this stunning exhibition, five recent large color prints of the D-Day beaches—Utah, Omaha, Sword, Juno and Gold—taken in evening light create a serene counterpoint to the visitors’ revelatory passage through the horrendous maze and offer consolation in the notion that the sand and surf of time effaces the scars from that tumultuous day. These gorgeous images hang opposite a wall of notes left by visitors, a sort of soul graffiti, and though larded with patriotic standards, God Bless the Troops and USA, there is also plenty of grief, remorse and a prayer to forgive the past. As I read them, I wondered if viewing this collection of images might convince anyone besides battle-hardened veterans of the absolute and complete waste of war. Or, if the path to the recruiting station passed through this museum exhibition, would any of those young folks looking for a job hesitate to join up? Maybe we can forgive the future? The room offers a shelf of brochures for veterans seeking help as they struggle with post-combat issues. The final exit is a retail shop where visitors can purchase other books of war photography and knick-knacks, but I find it offensive and tawdry to offer souvenir gummi Army Guys (flavor unspecified), hand grenade erasers (these come with a choking hazard warning) and other stocking stuffers as the finale to this difficult and very important exhibition.

Jonathan C. Torgovnik, American (born 1969), Valentine with her daughters Amelie and Inez, Rwanda, from the series “Intended Consequences,” 2006, chromogenic print, ed. #11/25, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, gift of the artist. © Jonathan Torgovnik

Hail to the curators! And hail to MFAH for mounting the show. Go see for yourself! There is a resplendent $90 War/Photography catalogue with seven essays that should provoke a continuing discussion that will hopefully carry well beyond museum and curatorial concerns.

Simon Norfolk, British (born Nigeria, 1963), Sword Beach, from the series “The Normandy Beaches: We Are Making a New World,” 2004, chromogenic print, ed. #1/10 (printed 2006), the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, gift of Bari and David Fishel, Brooke and Dan Feather and Hayley Herzstein in honor of Max Herzstein and a partial gift of the artist and Gallery Luisotti, Santa Monica. © Simon Norfolk / Gallery Luisotti

Here is the rest of Emily Dickinson’s poem, #749, written in 1863 and borrowed for this review’s title. Free.

All but Death, can be Adjusted—

Dynasties repaired—

Systems—settled in their Sockets—

Citadels—dissolved—

Wastes of Lives—resown with Colors

By Succeeding Springs—

Death—unto itself—Exception—

Is exempt from Change—

WAR/PHOTOGRAPHY: Images of Armed Conflict and Its Aftermath

Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

November 11, 2012 – February 3, 2013

________________________

Teacher, poet and combat veteran, David F. Brown lives in Houston and teaches in a public high school.

5 comments

David,

What can I say but thank you for this truly thoughtful and compelling review!

with much respect,

will michels

Good review. Totally with you on the gift shop – they are always fairly crass, some more offensive than others but this one really takes the cake.

Speaking of crassness, I don’t feel like it is right for members to have to pay $10 for repeat visits, either. Every once an while is one thing, the MFAH is making it a default move for ANY big show.

David…your words reflect a sensitivity reserved for– and reluctantly bestowed upon–one whose eyes smelled and tasted and listened to the air the moment the shutter clicked. Exceptionally well expressed review.

You picked the perfect poem for the occasion, you always do. Your review definitely makes me want to see the exhibit.

Wow! This review was beautiful and heart wrenching. It reminded me how important it is for people to be reminded of humanity. It made me reflect on my own opinions and hopefully I will be seeing this exhibit soon. Good job Mr. Brown!