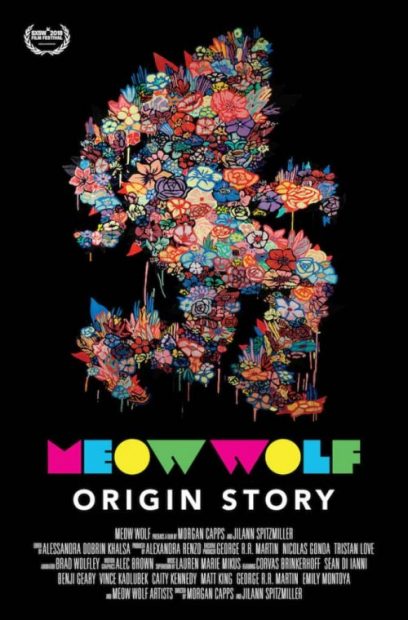

Last Friday night’s screening of the documentary Meow Wolf: Origin Story at the Texas Theatre for the Oak Cliff Film Festival in Dallas drew an enthusiastic crowd, indicative of just how beloved the Santa Fe-based permanent-installation art attraction is and has been since its opening in 2016. As one can read from the film’s popularity, there are a lot of people looking to the New Mexico-based art collective behind Meow Wolf to find out just how far that model can stretch.

The storyline is a familiar one to artists: a group of talented but ultimately aimless creative types struggle to produce compelling, accessible works while dealing with the difficult decision of whether to embrace or avoid self-incorporation, high-business dealings, permanent headquarters, and general structure. However, it’s ultimately fascinating, and at least a little upsetting, that the 200 or so artists behind this 10-plus year experiment appear to have little interest in locating their achievement along a historic timeline of arts-funding models. They fell into it, and now they’re exporting it elsewhere, to places like Denver.

Printing this story to film makes a lot of sense; if Instagram selfies can sell an art movement, then Meow Wolf’s immersive House of Eternal Return and its related cultivated aesthetic will surely look great on the big screen, and it does. If the collective is really as ambitious as its leader Vince (quoted towards the end saying that he wants Meow Wolf to grow into a ‘billion dollar company’), then they probably want to get in front of their own narrative sooner rather than later. But there are some questions that don’t get answered here. There’s a scene towards the final act where Meow Wolf members travel to scout new locations for its next permanent installation. How did Denver win out against Austin? Were there locations proposed by cities hoping to win a bid? The documentary fails to offer any specifics, but rather only the glorious success story of some art-school kids who made it big. There’s a lot of camaraderie, some heartbreak, and massive amount of fundraising that cannot be downplayed.

The documentary itself suffers from a common trope of the medium: animations and motion-graphic sequences where there should be more B-roll. With a subject like Meow Wolf (and the many years of installation experiments that came before it), we really don’t need to be pandered to with story-boarded anecdotes and backstory. The film does put a respectable effort into tracing the story in a ten-year chronology, exclusively through first-person accounts. Given the scope of this collective, that’s pretty impressive.

I asked one attendee, a Dallas-based creative person working in commercial real estate development, to offer some thoughts on how Meow Wolf could be thoughtful in their continental conquest of vacant lots and their expansion of installation-based spectacle:

“As malls and large-scale mixed-use retail developments across the country are made increasingly obsolete by e-commerce, the documentary seemed naïve to the massive real estate opportunity awaiting Meow Wolf. By creating an immersive, highly-Instagrammable art experience in a 20,000 square-foot space that generates a ton of foot traffic and has mass-market appeal, they are a mall landlord’s dream come true. Their business model will be less scalable — and perhaps less impactful — if they seek out spaces of that size in the core of highly desirable cities like Austin with already competitive creative scenes. If Meow Wolf were to go to third- and fourth-tier cities and engage local communities of artists and makers to develop each location, they could create a really impactful, sustainable model for national expansion.”