After more than two decades in Boston, Ambreen Butt moved to the DFW area less than a year ago, so this mini-retrospective at Dallas Contemporary represents a formidable Texas debut for a newly minted local artist. Curator Justine Ludwig skews the exhibition towards the artist’s recent practice, including only two examples of works made before 2010. These, from the artist’s Dirty Pretty series, epitomize the aesthetic indebted to her early training as a traditional miniature painter in her native Lahore for which she gained initial recognition—internationally, but especially in New England and New York. The pair of works on paper feature figures and animals derived from Mughal manuscripts, in particular a sumptuously illustrated late-sixteenth-century Akbarnama in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum. Gorgeously colored and rendered in a deft lapidary hand, the figures exist imbricated with line drawings of people in modern garb, traced from photographs of political protests in present-day Pakistan and often stitched in thread through layers of translucent vellum.

In The Great Hunt 1, from 2008, an imperious turbaned archer draws his bow at one side of an ornately framed circular medallion, while dancing girls sway gracefully at the other edge. A salient tiger, oddly vertical behind the archer, sheds his stripes, which engulf the maidens as flames do sinners in Mexican folk art. Between the groups, two women portrayed on a much larger scale—one outlined in thread and wearing sunglasses—appear to shout emphatically at an unseen target. Within the guise of a historical and culturally specific format, Butt overlaps past and present, patriarchal legacy and feminist agency—all of it inextricable from a context of conjoined beauty and violence. While the imagery and resonance of this work derive from subcontinental sources, it does not require a great leap of imagination to recognize its universal and constant relevance.

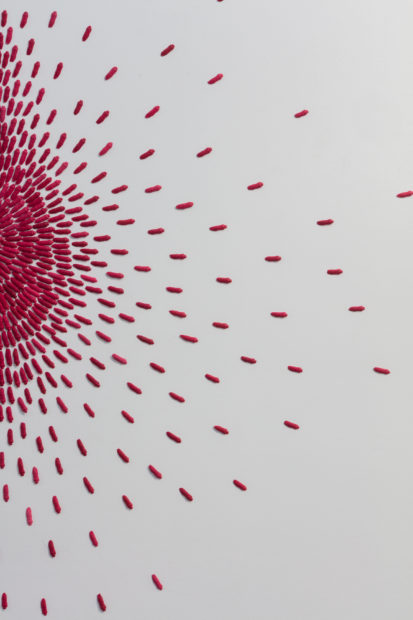

Elsewhere in this first gallery of the exhibition, multiple small, colored sculptural elements evoke brush strokes as they form radiating starbursts at corners of walls and on a low platform on the floor. The one on the floor, I Am My Lost Diamond 2, 2012, marked by concentric lozenges and rectangles in tones of red, orange, black, and cream, resembles a shaggy carpet. Closer inspection reveals the “strokes” to be odd little nubby caterpillars, which are, in fact, resin casts of body parts, mostly fingers and hands, a rather jarring device that nonetheless nicely conflates the art object with its means of production—the artist’s digits—much like some of David Altmejd’s plaster sculptures incorporating casts of hands digging into the material seem to freeze and thematize their own making. On the other hand, the sense of a human body blown apart and dismembered feels inescapable, and the artist has indicated as much, speaking of her concerns about a recent suicide bombing in Pakistan as she began the series. In contrast to the Dirty Pretty series, Butt here removes the intimations of carnage from the realm of pictorial representation. The increased level of abstraction somehow combines with the indexical, one-to-one relationship with the body in three dimensions to give these works a simultaneously more visceral and more decorative charge. The decorative in the case of I Am My Lost Diamond 2 hints at the craft arts of Muslim lands, making the work into a complex rumination on the specificity of contemporary terrorism, at least in its highest-profile instances in the media. That this work by an artist of identifiably Muslim background refers, even somewhat distantly, to religiously motivated terrorism with conjoined empathy, dread, and beauty—and does so with a degree of ambivalence of intent—may constitute its greatest achievement, and it’s one that feels distinctly American.

Butt’s turns towards the abstract, decorative, and sculptural find their most impressive manifestation in the show’s central gallery, sparely hung with three large reliefs that look for all the world like Islamic rugs or tiled panels—specifically the Multani tiles that ornament many a mosque in South Asia. Two are nearly identical in pattern, although one of these spans two walls, folded into a corner. The intricate symmetries of these works—each titled I Am All What Is Left of Me, 2015—are formed by resin casts of locks, keys, and coat hooks in blues, reds, greens, and yellows. They incite a gee-whiz respect for the ingenious craftsmanship, but even more a kind of awe at the rather stately grandeur produced by the prosaic forms. Again, the artist stealthily endows ravishing visuals with the potential to create uneasy subject positions for the viewer. If we take the carpets to signify Islamic culture, foreign and therefore suspect to a large proportion of her audience, then who has access to it? Who is locked out and who has the keys? Who gets left hanging? These questions can generate anxiety as the suggestions of violence do in other works, a fact that may be inferred by the commission Butt won to create a similar work, eighty feet long, for the American embassy in Islamabad, for which the works here served as models. At the embassy, instead of the locks and keys, the decorative motifs are picked out in more abstract forms derived from Arabic calligraphy, perhaps in an attempt to sidestep any hints of us versus them.

The exhibition’s third and final room holds a selection of Butt’s work in collage, including her most recent production. Five and Ten from a series titled In God We Trust (2017) are large, convincing blow-ups of a five and ten-dollar bills, respectively, painstakingly created from tiny bits of shredded currency. The attention-grabbing effect of their subjects and facture unfortunately overshadows any deeper interrogation of American political economy. Call Me a Blasphemy (2011) and Pages of Deception (2012) also address the intersection of religious mystery and the application of political power. The former rips apart the forty thousand individual words of Pakistan’s extensive blasphemy laws and reassembles them in looping concentric whorls to form a sort of cosmic doodle. The latter, a diptych, reconfigures opposing arguments from the 2012 trial of Tarek Mehanna, an Egyptian American man in Massachusetts who was convicted of supporting Al Qaeda, into facing pages from a Mughal manuscript. Cut-up words compose both decorative borders and the nested circles within them, which coalesce from white edges to dark, pupil-like centers. The utterances of prosecution and defense become equally incomprehensible mirrored abstractions, which look like huge eyes, staring implacably back at us.

The latest works, four smaller collages, are each named after a child or teenager killed by American drone attacks in Pakistan: Abdul Wasit (17), Fazel Wahab (16), Ayeesha (3), Hayatulla Khan Mohammed Tahir (17). Even the titles of the works in this 2017 series called Say My Name, simple transcriptions of names and ages, begin to inspire mixed emotions—sadness, to be sure, but also revulsion at the deaths caused in our names, often callously elided from public awareness as “collateral damage.” Like the words in Call Me a Blasphemy, the names, or fragments of them, printed on colored paper and gently torn into shreds, spiral towards a dense center in each work, whirlpools sucking young lives and identities into oblivion. Each has a different overall hue: red, chrome yellow, rose madder, blue. As our eye follows the repetition of the individual names, our reading becomes a mantra, a prayer, or a protest, and the collages resolve into mandalas for meditations on grief and resistance. These four modest works are Butt’s most abstract, but also her most harrowing, and her labor-intensive process can be seen for what it has always been, a means for calling attention to things too important to be overlooked.

Through August 20th at Dallas Contemporary. Images by Kevin Todora and courtesy of Dallas Contemporary.