It’s a great irony that, in the age of accessible digital media and internet movie streaming, our cinema landscape has narrowed in many ways. The offerings of Netflix and iTunes don’t come close to representing the breadth of movie experiences that a few independent theaters and video stores brought me as a budding cinephile and young student of the human condition. Along with the rapid disappearance of our moviegoing rituals, spaces, and presenters, the world is also losing something even more alarming: the movies themselves. Unable to easily justify film preservation, distribution, or even storage, studios and universities have been neglecting and trashing countless film prints. This has made things difficult for our few remaining film exhibitors, and threatens to prevent some of the most unusual and adventurous fringe cinema from ever being seen.

Thankfully, some hairbrained heroes in Austin, Texas have been going to great lengths to raise cinema’s dead. I recently visited with the folks who operate the American Genre Film Archive (AGFA), a non-profit that has saved thousands of orphaned 35mm prints of feature films made between the 1950s and the ‘90s from becoming either lost or landfill. AGFA’s eclectic approach to collection and its integrated mission of actually getting the films seen by audiences distinguish it from most archives. Rather than focusing on certain celebrated artists or genres, their wide-ranging explorations are driven by a belief in the potential cultural worth of the wildest of underappreciated movie misfits. AGFA continually discovers unique, independent visions that rival the edgiest of today’s so-called independent films and contemporary art film and video works. They also frequently discover that their print of a film is either the best or the only known surviving copy–on any format.

This all began with the efforts of Alamo Drafthouse Cinema co-founder Tim League and deep-digging film programmers Lars Nilsen and Zack Carlson to find forgotten gems that have fallen through the cracks of both popular movie outlets and academic film archives. Their finds led to the formation of AGFA in 2009. Its ongoing efforts to collect, preserve, and loan out rare prints of marginalized movies are now managed by Sebastian Del Castillo, with Joe Ziemba, Laird Jimenez, and Tommy Swenson initiating special projects and public programming.

Ranging from classics to pop schlock, from arthouse to grindhouse, AGFA’s funky collection has been amassed through a series of unusual search-and-rescue missions. They rushed to retrieve prints of martial arts movies that were stored under the floorboards of a Vancouver BC nightclub (formerly a Shaw Brothers moviehouse) before the building and its contents were demolished. They traveled to California to save a huge haul of film prints from, apparently, being dumped into the ocean. They mined a large collection of sexploitation movies, porn, and various B-movies that had been that had been sitting in an Indiana warehouse, untouched for decades.

The truckloads of 35mm film yielded from such archeological adventures create a continual and challenging process for AGFA’s Chief Archivist Sebastian Del Castillo, who gradually works through organizing, inspecting, cleaning, and repairing films in the collection as well as distributing the best of them for exhibition in venues around the globe. The rescued prints are sometimes deteriorated beyond saving, or missing large sections. Sebastian is often elated to discover a rare print that is complete and in great condition, but he’s just as often made nauseous by opening a film can to find rat feces or the overwhelming smell of “vinegar syndrome” (a form of film deterioration that not only smells awful but is contagious and so must be kept away from uninfected prints). Such is the dirty work of post-apocalyptic cinema scavenging.

AGFA’s Instagram provides a window into the inspection process, with posts of unusual film frames as well as beautiful deteriorations that are currently under the loupe.

AGFA’s relationships with Alamo Drafthouse Cinemas and with Austin’s freakishly enthusiastic movie audiences have allowed for some of its archival explorations to take place in public, on the big screen, and in good fun. They hold regular “Reel One” parties at Alamo theaters to investigate the first 15-20 minutes of various mystery films in the collection, allowing AGFA folks to note the specific content and condition of the prints while at the same time gauging audience reaction. This is a rare kind of community engagement for an archive, and it has led to further exhibition and distribution of some of AGFA’s more crowd-pleasing ‘70s and ‘80s head-scratchers, including Miami Connection about a martial arts synth-rock band battling motorcycle ninjas; Mexican slasher movie Don’t Panic; deranged reptile revenge movie Snakes; and Get Crazy–director Allan Arkush’s outrageous follow-up to his Rock and Roll High School.

Besides screenings at local and national Alamo Drafthouse theaters, 35mm prints from the collection have been exhibited at venues such as Anthology Film Archives, BAM Cinematheque, Lincoln Center, George Eastman House, Museum of the Moving Image, and the American Film Institute. In fact, AGFA loans out prints for hundreds of screenings each year at theaters, film festivals, and museums in New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Boston, Dallas, Nashville, Portland, Montreal, London, Singapore, and Brisbane. In the years since it began, they’ve seen a growing interest among exhibitors in showing the kinds of unsung oddities that can’t be found anywhere but this unusual Texas wellspring.

AGFA has recently announced plans for a new collaborative project involving the collection of Mike Vraney, whose Something Weird Video label was responsible for the rediscovery of countless forgotten movies by filmmakers such as Herschell Gordon Lewis, Dave Friedman, Doris Wishman, and Ed Wood. They’re working with Vraney’s widow and partner Lisa Petrucci to house, restore, and distribute select movies from the Something Weird collection, beginning with the unusual 1971 “tabloid horror” film, The Zodiac Killer. It’s a personally meaningful project for much of AGFA’s staff and supporters, for whom Something Weird’s VHS releases in the 1990s provided an influential alternative film school.

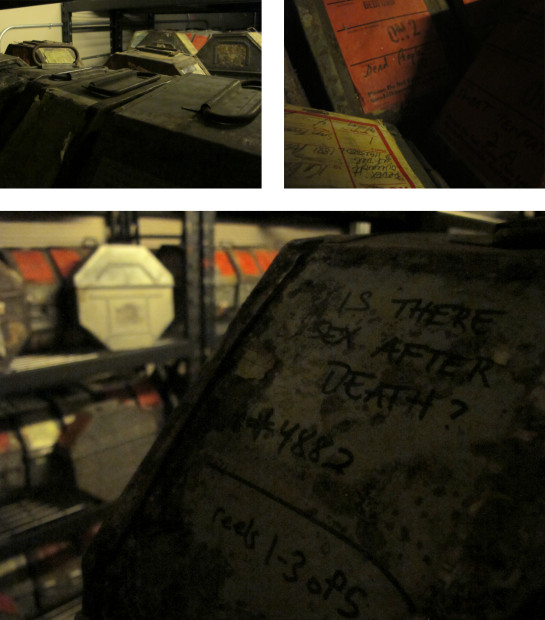

While we think of works of cinema as ethereal light and sound experiences, it’s important to remember that actual analog 35mm movies are also physical objects–long strips of tiny rectangles wound on round reels and housed in heavy octagonal containers. Of course, each of these vessels holds a unique cinematic work: the result of creative visions, collaborative efforts, cultural signifiers, and commercial concerns. In addition, the artifact itself indicates its own individual history–the delicate film inside baring evidence of its projection over the years, and the bulky exterior armor reflecting its rough-and-tumble travels between activations.

I was given a rare tour of AGFA’s facilities. As I walked with Del Castillo through its thousands of prints I thought about the various suspended realities in this habitat for castaway films, and I appreciated the evolving physical and conceptual montages that its holdings create. I imagined the immense collective weight of it all, the various paths that have come to connect at this unlikely depot, and the countless invisible heroes, villains, angels, and demons living there, waiting quietly in the dark. I poked around the shelves and stacks, catching glimpses of random film titles that strung together like odd collaged poetry. The word “Shadows,” hand-scrawled on a metal can, seemed to me a good metaphor for what’s being collected and investigated en masse here. Ironically, that movie–a relatively well-known independent film by John Cassavettes–is one of the less endangered prints in the collection. But seeing recognizable arthouse films and pop classics sitting alongside rare movies of every kind imaginable (and unimaginable) drove home the spirit and importance of AGFA for me. This physical mass of uncategorized cinemythological funk reflects the grand messiness of the human endeavor.

I love AGFA’s movie discoveries so far, and I love that this Austin-based archive is feeding screens around the globe. But this thing has really only just begun. I’m more deeply impressed by the spirit that has made these kinds of explorations possible: a defiance of cultural and capital hierarchies. This resource for endless cinematic rediscovery and cultural connection is fueled by film enthusiasts’ continual steps outside of the norm and into the unknown–beyond accepted labels and definitions, beyond market trends, beyond their own expectations, beyond even logic. In short, AGFA is built on heroic suspension of disbelief. In an era of hasty categorization and rampant cultural deletions, long live the hardcore dumpster divers.