The American West is an image of new beginnings, and also a melancholy image. It’s suited to the longings Americans feel programmed for: longings for different places, different times, and different circumstances.

According to press materials for Occiput, Lucia Simek’s exhibition at The Reading Room in Dallas, when a situation of grief and doubt broke into her life about a year ago, Simek packed her three children into a car and headed west. Video and pictures she shot with her smart phone on this trip developed into the two-channel video and digital prints that make up most of this exhibition.

The two channels are projected into a corner of the room and the conversion of these images creates an effect like highway driving. In this way, Simek puts the viewer on a journey, too. Her story blends into the viewer’s story. The images are vivid enough to evoke a westward passage. Even the virtual journey can spring the reflex of nostalgia.

Nostalgia is the important experience in Occiput. Not nostalgia as a wistful “remember when” that lasts as long as a chorus in an old pop song, but rather the red meat of the matter: nostalgia as deep consideration for old triumphs and old wounds. Nostalgia as an invitation to that point of receptivity, back when we felt on top of our game or stripped raw by humiliation; a point when we felt anything might happen. A point just before our senses started to seal off and we began the work of normalizing our experiences and developing a definitive sensibility. Nostalgia can act as an aid—when our plans crumble beneath the weight of circumstance—by drawing us back to a more primitive state in our critical development. It serves as a reminder that nothing grand or terrible is permanent. It is an invitation to draw from old ways to make new ways.

There is a sense of inevitability in the way the clips are arranged in the Occiput video—those familiar “let’s stop and look” images that enrich our road trips: tall grass waving in the breeze; rocky hilltops; docile livestock—a sense of inevitability Simek arrives at by skillful editing. There are also plenty of highly inventive rhymes between the images in the two channels. Highlights include a rhyme made out of the movement of flies lifting and landing on a window screen in one picture, with the motion of field grass lifting and falling in the wind in the adjoining one. And a rather complicated rhyme about natural light: a ceiling fan light, switched off or burned out, dripping with a busy spider’s web in one picture while in the other picture a double rainbow adds charged light to a yellow field of grass. The double dip of the spider web is an odd and wonderful match with the double arc of the rainbow.

The sense of inevitability in highway driving that Simek evokes through editing is occasionally cracked open by surprises: images that drop in from other places; images that are bizarre and funny; images that seem religious. One of these interruptions shows us the interior of the Yale library. Another treats us to an iffy lounge act going for broke in some highway watering hole.

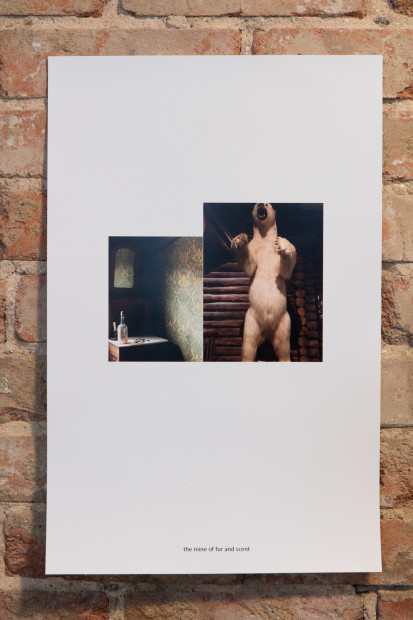

Simek’s inspired craft of picture rhyming is also on display in the digital prints. In the print titled the mine of fur and scent, the tall patch of white sunlight that illuminates an antique wallpaper pattern in one image makes a rhyme with the tall white polar bear standing before an antique cabin wall in the other.

Occiput takes its name from the anatomical term for the back of the head. The occipital lobe of the brain is the place where information from the eyes is interpreted for the mind as a scene, joining a sense of place and time. This job of interpretation is one the complex enterprises that separates talk of the brain from talk of the mind. We tend to use the word brain when we talk about neural pathways and biological programming. We tend to use the word mind when we talk about the conversion of sensory information into the story of our lives, the story of the world, even the story of the cosmos.

A discussion about the mind makes for lively gallery talk, which I expect is Simek’s intention for putting her work under the sign of the cranium. The mind is a thickly populated world of ideas, ideals, and intentions that cannot definitively be accounted for by the physics and chemistry of the brain. The world of mental phenomenon—a realm of intelligence and creativity—resists the reduction of simply being understood as world created out of the activities of molecular chemistry. In other words, a thorough discussion about the mind will involve mystery, faith, and our inherent longing to belong to something much larger than ourselves.

Occiput is a generous and refreshing experience. Simek uses images from her westward journey to convert private pain into object lessons about the wondrous connectivity and complexities that light up everyday life.

Occiput runs through October 3rd at the Reading Room, 3715 Parry Avenue, Dallas.

Photos by Kevin Todora.