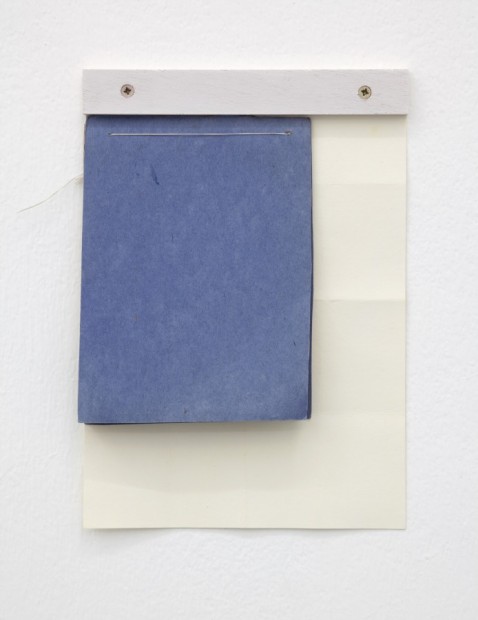

Fergus Feehily, Yard, 2010, Acrylic and found book on paper, oil on wood, screws 8 1/4 x 5 7/8 x 1/4 in. Courtesy Galerie Christian Lethert, Cologne © Fergus Feehily

Curator Jeffrey Grove selected Fergus Feehily and Matt Connors for Concentrations 54 (both enjoy their first museum exhibition here at the DMA) because of the quiet little trail the two are blazing in the current story of painting. They are unlikely trailblazers because their work is so decidedly hushed, and often very small, especially in the case of Feehily. It is work which, as Fergus Feehily described it, is “resisting success” through a calculated practice of restraint. The result of that resistance on the part of both of the artists (whom had not met each other until the installation of this show) is work that is open, vulnerable and modest. But, in its quite nature, the work of both artists belies an urgency to reorient a loud, fraught world (perhaps the art world, explicitly) toward something more essential. Peace, maybe, or at the very least, a collective shush.

Fergus Feehily’s paintings are almost shockingly slight, all roughly the size of an 8” x 10” photograph, and in that they call a great deal of attention to themselves, especially in this museum setting where one expects to be dwarfed by enormously sized masterpieces. Their diminutive size immediately re-engages a weary art-viewer with the wall, exerting a kind of magnetic pull—they beg to be inspected, and there is much to encounter in these deceptively simple paintings.

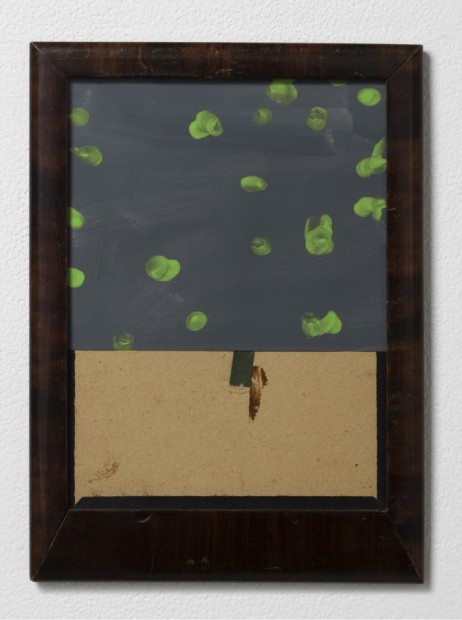

Fergus Feehily, Courtyard, 2010, Gouache on paper, found frame 11 x 8 1/8 x 5/8 in. Courtesy of Misako & Rosen, Tokyo Collection of Nodoka Kinsho © Fergus Feehily

Employing found frames, papers or fabrics, Feehily’s paintings are often constructed by stacking a collection of materials and binding them together under bands of wood at the top and bottom of the piece which are then screwed directly onto the wall. In many of the paintings, Feehily has allowed the stacked fragments to dangle down from the top band of wood, rendering the painting the appearance of a legal pad notebook, some complete, if you look hard enough, with scrolled notes from some other notebook from some other note-taker, as in Yard (2010). Pieces like this suggest an engagement with history, or perhaps more aptly, memory, that is deceptively masked behind the spare overall effect of the work. Small fabric remnants with tattered edges fastened above a smoothly painted piece of wood make for paintings that are poignantly, inescapably melancholic, while at the same time feeling as benign as a swatch tacked to a decorator’s mood board. That sort of polarity, between the transcendent nature of things and their surfaces, runs through all of Feehily’s work.

Matt Connors, Foil, 2011, Oil, acrylic and colored pencil on canvas 32 x 22 in. Courtesy of the artist and Cherry and Martin, Los Angeles © Matt Connors

For example, a few of the artist’s works use found thrift store frames, the sort one would use for kids’ school pictures or a shot of happy vacation frolicking and yet, while cheap, they connote an intimacy with whatever they frame. But Feehily uses the frames to house something colorfully blank, as in the tiny work Provisional (2009)—a side-by-side frame that holds a pink painted paper on one side and a green one on the other—or gently tousled with paint, as in Courtyard (2010). In doing so, he is trapping space and artistic mark-making within the container of the portrait frame. In these pieces, Feehily suggests that each artwork is itself a kind of individual entity, removed from the viewer yet intimate.

The artist has also added dynamism to the show by including three pieces from the DMA’s permanent collection that correspond to his notions of space/containment, scale and surface: an embellished seventeenth century jewel casket, a tiny black African bead with white painted stripes and a seductively rich Indian miniature depicting a gathering of figures at the threshold of an archway ensconced by a garden. These art historical works help foster the subtle yet evident connection to history present in Feehily’s thinking, while at the same time reminding us of the mysterious treasure trove of the museum itself. By pulling these works out of the vault, so to speak, and allowing them to dialogue with his paintings, Feehily compounds and enriches his already deft and layered archeological art-making.

Matt Connors, Primary, 2011, oil, acrylic and colored pencil on canvas 60 x 45 in. Courtesy of the artist and Cherry and Martin, Los Angeles © Matt Connors

Where in his small works, Feehily asserts a nearly defiant pose against the last century’s “heroic tendency or tradition in abstract painting,” as he told Curator Jeffrey Grove, his Concentrations 54 counterpart, Matt Connors, carries the weight of the Abstract Expressionists that Feehily both refers to and diverges from. Not coincidentally, galleries adjacent to Connors’s and Feehily’s, present a moderate selection of Abstract Expressionist works from the museum’s collection. Connors’ work, when seen immediately after walking through the previous galleries—replete with Kline, Pollock, Krasner Motherwell, Sam Francis and Morris Louis, among others—is very clearly culling from the “heroic tendency” of all these big wigs. His mid-sized, stained and delicately marked canvases refer unabashedly to Louis, and also very much to Sam Francis, but there is a wavering sort of mark that Connors uses that makes for a smokier, hazier, more dubiously natured quality in his paintings than that of his predecessors. It is what the artist called, in a talk about his work here, “a monumental presentation of doubtful marks,” which certainly goes against the grain of all the big AB EX certitude and visceral unquiet. Matt Connors’ canvases reveal a duality in his mark-making, sometimes spinning out into highly emotive, layered mark-maps. As an example,the painting Foil is layered with stains, sprayed dots, swipes as well as a recurring crescent shape. Meanwhile, a work like Small Resist harnesses barely a whisper of paint in its childlike and unstudied curved lines and blotches.

There’s something punkish about Connors’ ability to riff on the visual themes of Modernism’s masters. On the one hand he employs some of their methods, like staining the canvas directly with liquidy paint like Morris Louis or creating blotchy configurations that echo Clyfford Still. But on the other hand, Connors give them a little kick in the jaw with lyrically spare surfaces peppered with small, uncertain marks that feel like a song full of notes without harmony. Feehily’s observation about “resisting success” is incredibly apt—Connors willfully holds back from letting a work become a powerful, volcanic, post-War painting symphony. His paintings tinker with modes—applying an incomplete colorful frame to a piece called Large Correspondence (Narrow/Warm), a painting with vertical bars and jolted pencil lines, ribbing the Abstract Expressionist’s perfect, museum-hang-worthy frames. Subsequently, Connors dismantles the particular sanctimony that surrounds that tradition.

But Connors’ work does a great deal more than fracture the twentieth century’s painting paradigms. He describes his painting as the “image of thinking”—a record of choice-making, essentially. Experiencing them, as with Feehily’s work, is a lesson in human frailty and life’s insurmountables. Their art allows weakness, and that’s a powerful gift.

Concentrations 54: Matt Connors and Fergus Feehily

Dallas Museum of Art

Through August 14, 2011

Lucia Simek is an artist and writer based in Dallas. She and her husband, Peter Simek, founded the much-loved, short-lived arts and culture site Renegade Bus in 2009. She has also written for THE Magazine and People Newspapers, and is currently a frequent contributer to D Magazine‘s arts blog, FrontRow. She also acts as the arts commentator for the kids blog Tiny Dallas.

2 comments

very nice Lucia. Excellent to see in the DMA.

[…] in the permanent collection; to balance this with the big retrospectives; to invite artists like Matt Connors and Fergus Feehily to work with the permanent […]