Right up the ramp from Jackson Pollock’s smeary, spattery pathos in the Dallas Museum of Art (that fine show is closing this weekend; see it if you can), there’s a tidy little master class in one reaction against all that emotive paint: a cold, clean, antiseptic room of three light sculptures. I came to see the Pollock; what struck me was the light.

In one of the DMA’s quadrant galleries, curator Gavin Delahunty has installed one work each by Robert Irwin, Dan Flavin and Stephen Antonakos. The pieces are stripped down and bare, scientific even, as is the room they’re presented in. There are no lights in the gallery beyond the artworks.

Here are three important artists doing the same thing, very differently. It’s an elegant and interesting moment, one of those pleasures for which the quadrant galleries at the DMA seem specially designed.

Irwin’s piece, one of his more recent wall sculptures where he uses gels over florescent tubes to create patterns of stripey color, greets you at the entrance, framed by the door. It’s a ‘ta-da’ moment meant to draw you in, and it succeeds. But it’s arguably not the strongest example of this body of work. In bare-bones green, black and yellow (and unclad white tubes) the point that you believe he’s trying to make—where you see the colors made by colors, the nuances in the spaces between the tubes, and you hum with awareness of the adjustments your eye and your mind are making to make sense of what you’re seeing—doesn’t succeed as well here as in similar pieces he’s made. Perhaps because of its limited, sickly colors, or perhaps because of its domesticated size (Irwins often run the entire length of long walls), this particular Irwin is an eye strain, like the op art it perhaps unwittingly evokes.

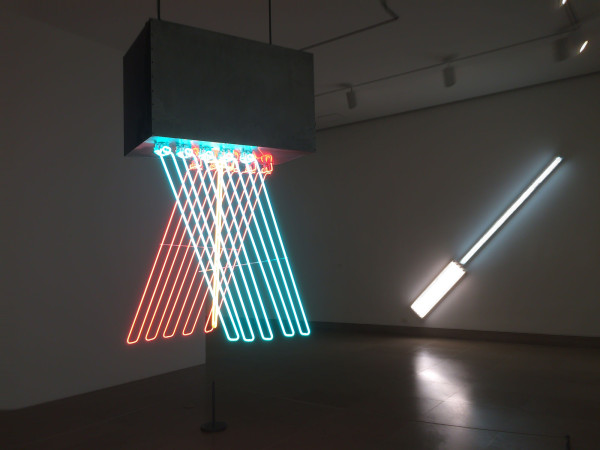

L: Dan Flavin, alternate diagonals of March 2, 1964 (to Don Judd), 1964, daylight and cool white fluorescent tubing R: Robert Irwin, Little Jazz, 2010, neon glass.

To the left inside the gallery is one of Dan Flavin’s familiar white florescent abstractions—a big, impassive syringe that’s tilted on the wall, titled alternate diagonals of March 2, 1964 (to Don Judd). There’s a barely perceptible variation in the color of the white tubes (the long protruding one is slightly bluer than the group below it), and one friend commented on the irony of exhibiting Flavin today: these industrial tubes, which would have been cheap and easily available when the work was made, must now be fussily and expensively recreated. Value, both of materials and of human activity, is a funny thing with art. (As the artist Nestor Topchy recently commented on Glasstire, the value of the materials in the Mona Lisa is probably about $70.)

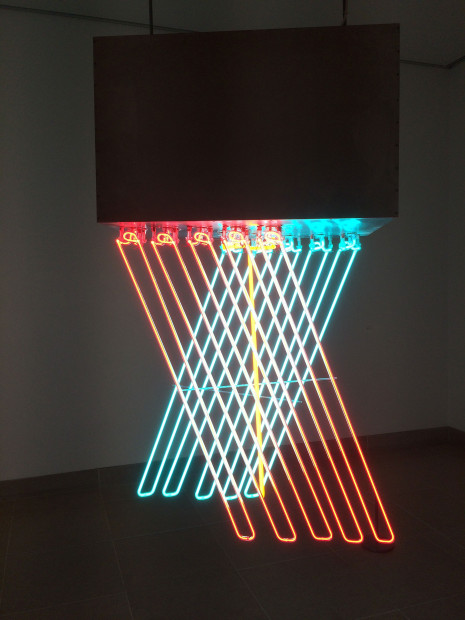

Back in the light room, what the DMA really wants you to pay attention to is its new acquisition, which is the least familiar work in the room: Stephen Antonakos’ Hanging Neon from 1965. The two wall texts in the gallery primarily discuss Antonakos, taking Irwin and Flavin as read. They highlight the ways Antonakos’ piece is different from Flavin’s (custom neon vs. commercially available tubes; inverted light hanging from the ceiling rather than mounted on the wall). One text even rather truculently argues for Antonakos at the expense of Flavin: “It was not until 1989 that Flavin began to suspend his light sculptures in space. Prior to this, the work of Flavin and other artists was tethered to the wall, restricting full access to seeing the work in the round. Hanging Neon, however, was entirely accessible to viewers, who could walk around the work in 360 degrees, emphasizing the spatial nexus of viewer, artwork, and architecture.” It almost reads as if Delahunty is suggesting that Flavin eventually got around to copying Antonakos, that a light sculpture on the wall doesn’t have a three-dimensional quality (that light itself doesn’t have a three-dimensional quality), and that Flavin hadn’t considered these things when he made alternate diagonals.

But I don’t believe that’s Delahunty’s point. The overall installation is thoughtful, and respectfully considers the Antonakos in the context of two more famous light works (the selection of which notably omits the DMA’s neon piece by Bruce Nauman, Perfect Door/Perfect Odor/Perfect Redo—which might not have fit the austere vibe.) I appreciate seeing Delahunty’s argument for something different. It’s refreshing, and the opposite of the rather silly Vermeer show elsewhere in the museum, in which the artist’s name shouts into the hallway on the strength of one lesser painting alone.

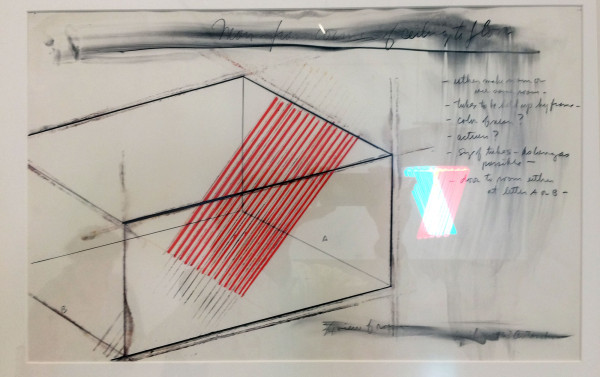

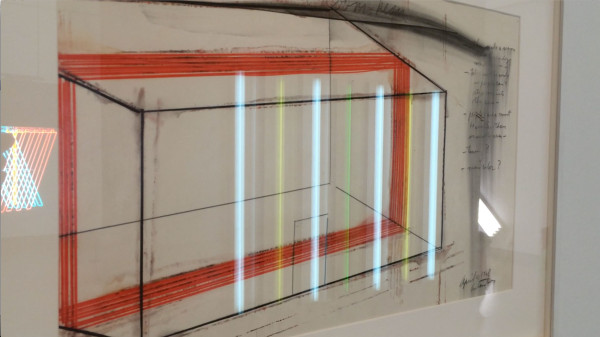

The light room also includes a group of Antonakos’ drawings, which are masterful and confident, and installed so that reflections of the light sculptures are inescapable. Perhaps it’s not the best viewing conditions for drawings under glass, but it serves Delahunty’s point that the drawings “simulate the effect of emanating light on our perception.”

In a gallery of artists using light as their medium, it would be fun to also see works by neon artists Keith Sonnier and Chryssa given this kind of serious consideration. Perhaps the DMA will go on to acquire works by them.