“Art is everywhere, except among the Art dealers in the Art temples, the way God is everywhere, save in churches.”

– Francis Picabia

If you’re a rich person who dies in Houston, it often goes something like this:

You, or rather the cold, meaty vessel of you that is left behind, is taken to a well-appointed place, where your family and friends convene for your final send-off. A uniformed policeman directs traffic outside in the street, a courteous doorman is wearing white gloves and a hat, and staffers in somber business attire greet everyone with their respectful voices. Your family and friends wander amid rooms of mahogany, chandeliers, rugs and oil paintings. Boxes of tissue are conveniently placed throughout in tasteful wood dispensers. Servers materialize offering drinks and canapes. A string quartet plays sonatas. Your family and friends make their way into a gym-sized chapel, where they settle in front of a non-denominational altar flanked by two large video screens.

This is where everyone will say goodbye. To you.

Observed dryly in the context of an art exhibition, without the bleaching effect of grief to strip away one’s capacity for critical observation, this all seems pretty bizarre. But I think the artist Nestor Topchy’s recent exhibition Eternal Now was designed to draw attention to that very bizarreness, while also gently reminding us that the fancy funeral of the 21st century is no weirder than anything else human beings have done when people die. We want to bridge that impassable divide, and we’ll try anything to do so.

Eternal Now was a one-night exhibition — or more accurately, an Everything: performance and social sculpture and immersive installation, with painting and sculpture and found art — all of which seeped into every crevice of the Geo. H Lewis Funeral Directors in Houston, and which extended out into the parking lot and even the street, with the traffic cop and doorman acting as unwitting performers in Topchy’s Gesamtkunstwerk.

Taken in the largest context (since context is everything), the funeral home — the building, the people within it — were selected by the artist, “placed” as they are in the midst of bustling life. Topchy’s choice of setting itself was a gigantic found sculpture, and that night, we were all in the sculpture. It was truly immersive, in the way most selfie-driven installations can only dream of being.

Topchy somehow got the funeral home to pull out all the stops, just as they would for a real death. As we visitors arrived, these mortuary people in their somber clothes and somber voices invited us to explore the whole building, and would we care for a glass of wine? I wonder: did these people know who they were dealing with? Did they know that Topchy has an alter ego The Brown Klown, who traffics in absurdity and pathos and shit, or that he used to perform in a costume covered with spurting penises? If they had seen that, would they have let him in their cut-glass door?

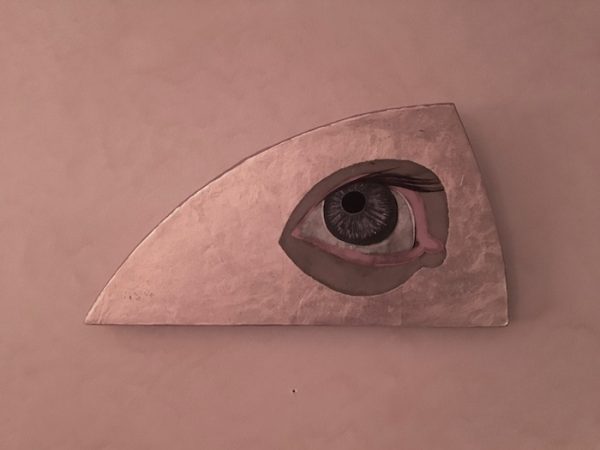

No matter. Topchy used the setting and the people in it not as an ironical backdrop for art tchotchkes, like so many shows we’ve seen in non-art settings — gas stations, convenience stores, mansions for sale, hotels — but as an integral part of the work itself. And in that context, Topchy’s own art tchotchkes (found or otherwise) came to life. He had placed his paintings and sculptures (the latter of which were painted Yves Klein blue) throughout the building, as well as fake plastic food, which like the funeral home’s tissue boxes, were discreetly placed on surfaces everywhere. And did I mention the performer dressed as a mermaid cheerfully waving at visitors in front of the funeral home’s massive aquarium?

Presented in a museum or a gallery, these things would have fallen flat. But somehow in this grand house of death, the works were alive, rich with layers of meaning, dense with Topchy’s amiable little jokes. The venue was not an empty gallery space — an empty vessel — but was decidedly full, of stodgy furniture and pre-determined symbolism and meaning.

And Topchy managed to thread the needle where Eternal Now didn’t come off as a critique of the ritzy funeral home, but rather a kind of sincere appreciation of the humanity of the whole thing. The event telegraphed a generosity of spirit even though — perhaps because — Topchy’s work is infused with his history of having always made the wrong art-career choices: by making supremely unfashionable work (egg tempera icon paintings and traditional Ukrainian decorated eggs); and by working at the fringes of the art world, or outside of it altogether, as a longtime performer in places that would now be considered established arts venues, but which would not have even been close to being on the radar of patrons or cognoscenti in their origin years.

A 2012 performance by Topchy at Lone Star Explosion. Photo by Vasyl Dijak.

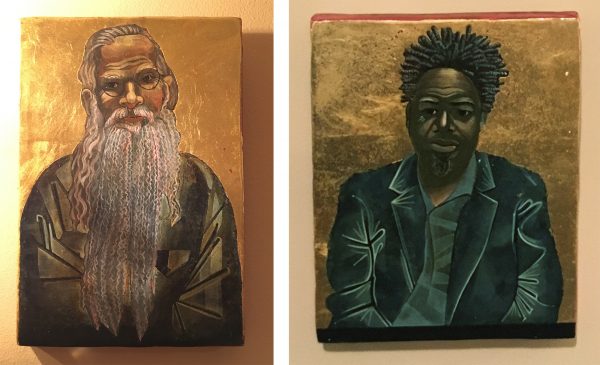

It is no accident that this most unorthodox artist makes almost ludicrously traditional work. His wax resist-dyed pysanka eggs are made according to that ancient, pre-Christian tradition, and the materials in his paintings are exactly those you would find in a Byzantine icon: wood with cloth and hide glue covered with gesso made from marble dust and chalk, followed by a painstaking process of applying egg tempera and gold leaf. Topchy often alludes to his childhood, decorating eggs with his grandmother and attending an Orthodox Ukranian school in Bound Brook, New Jersey, where there were icons in the church. In the past, he said of his icons, “I thought, why not just look back into familiarity? I’ve been through the same experiences as just about every artist. There’s a materialism that justifies just about every absurd and worthless notion for making art. I didn’t know how to step out of it, so I stepped out of it intuitively. I think embracing mystery is an honest and forward-thinking way to get something done.”

Icons are not true portraits. Their goal is not to capture the likeness of the person, but their spirit: if you worship this little flat, golden, idealized Jesus or Mary, perhaps your wish will come true. Likewise, Topchy’s series of artists, curators, directors, and various hangers-on are not particularly flattering or even sometimes recognizable, but they capture the spirit of the Houston art world, if the Houston art world were something ancient that we were looking back on through the lens of centuries.

In the gnostic book Acts of John, the apostle chides a follower who is worshiping his portrait, saying “you have drawn a dead likeness of the dead.” Of course, many of the people in Topchy’s icons (myself included) are still alive and were there at the funeral home that evening trying and pick themselves out of the proverbial lineup. But he paints us flat and implacable, an abstracted idea of people long since gone.

Like everything else Topchy does, these icons don’t feel like someone trying to be clever, yet they still have the whiff of the jester about them. They’re frankly weird. Topchy is a trickster and a clown, daring us to like his fusty icons, and to recognize how we worship in the church of the Houston art world.

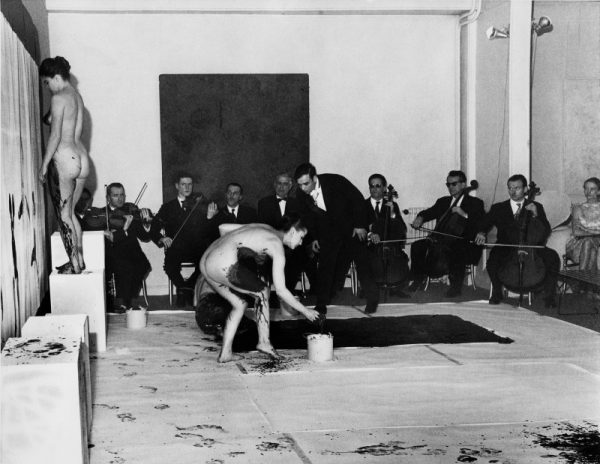

Elsewhere, the spirit of Yves Klein was evident in the proceedings, as it has been throughout Tophcy’s career. In his 1961 Chelsea Hotel Manifesto, Klein wrote, “I am particularly excited by ‘bad taste.’ I have the deep feeling that there exists in the very essence of bad taste a power capable of creating those things situated far beyond what is traditionally termed ‘The Work of Art.’”

Topchy has always tapped into this idea, which is all about wanting out of the art world, rather than in. It’s also about the death of art as we know it, and that night in the main chapel of the funeral home, Topchy’s rough spherical sculpture on the altar was painted with International Klein Blue (IKB). To further drive the point home, the huge video screens on either side were turned on, but left in their default glowing blue state, a close facsimile of IKB.

IKB is eternity. The Void. Just a little something Topchy, via Klein, whipped up for you to sit in a pew and contemplate. And Topchy got us there without sourcing very much fussy, difficult-to-obtain paint or making overwrought, morbid Rothkoian gestures about the infinite and the sublime. He just turned on the video screens and didn’t show a video. I love the lightness and the humor of that simple gesture, loaded with art historical baggage as it was.

Even the formal wear of the mortuary staff itself echoed the formal wear during Klein’s performances, as did the chamber orchestra:

But hands down, the coup de grâce was the plastic food. Topchy was inspired to use the kind of realistic fake food that is used to stage houses for sale or furniture showrooms, and place the stuff around the funeral home.

A still life of fake salad: transubstantiation.

A fake T-bone next to a tissue box and “mourning couch”: nature morte.

A trinity of fake bacon: the body of Christ.

A plate of fake Whataburger: put it in a box to go, just like Grandpa.

What is the difference (Topchy asks us to question) between a styrofoam steak and the embalmed bodies that normally inhabit this space? The Brown Klown has gotten away with murder, and it’s shrink wrapped right before our eyes. Of course, in Topchy’s life-and-death totality you can’t have nature morte without a corresponding tableau vivante, which (I am guessing) is where the mermaid came in.

The Jester is the one who speaks the unspeakable, and he can get away with it in front of the king, meaning in front of the orthodoxy. Topchy adheres to the rules, but he also gets away from them, which is a very delicate balance. That night he plumbed the depths of art history, from the ancient (painted eggs) and the Renaissance (icons) all the way through recent Modernism, anti-art performance, and video. There was the found art thing (the plastic food), the context thing (the funeral home), and the death of art thing (Yves Klein). It was all in there. Tapping into religious iconography, design, death rituals and contemporary merchandising is not something an artist can crank out overnight, or for a student exhibit. This kind of an event — less an event than a profound statement of what it means to be human — takes years of study and practice for an artist to pull off.

It was only after the fact that I wondered how many of us visitors seriously considered the inevitability of our own cold and meaty vessels being left behind for… something, most likely some kind of service for the living to remember us. How will you connect to the living once you’re gone? Because clearly that’s what Topchy’s project is about: not life-or-death, but life and death, the two states circling each other literally, through repetitions of spheres and circles in his artworks, and figuratively, through his icon paintings and his fake food.

Topchy has been one of the relatively unsung conceptual artists of the Texas art scene for a long time. To recognize the great art in your midst that swims against the stream is not easy — there’s a reason so few patrons collect with the iconoclastic eye of a Dominique de Menil, and so few curators are esteemed for having the prescience of a Walter Hopps — and Topchy is one of the people in Texas who has been swimming against the stream, right here in our midst, for a long time. Eternal Now offered the rare pleasure of a fully-formed, all-in effort by an artist presenting art like an onion to be peeled, layer after layer, meaning after meaning.

‘Nestor Topchy: Eternal Now’ took place on April 7, 2018 from 6–8 pm at George H. Lewis and Sons Funeral Directors, Houston.

3 comments

I really appreciate this look at my work

I hope nothing comes back to haunt me.

That said, I came up with the name Brown Klown in complete ignorance of cultural associations – I was thinking of a character from Dr. Seuss, a Mr Brown and borrowed for my Klown who shook hands loaded with chocolate cake icing at a fundraiser for Infernal Bridegroom in the early 90’s.

This is probably related to the Sculpture/Art Car class I taught at Houston Community College one year where we built a dysfunctional family home on a stripped Cadillac chassis replete with flushing toilet, sink and bed all soaked with clay slip, a very brown and runny staple of ceramics. The students hugged spectators all along the parade route, leaving hundreds of muddy prints on folks white shirts.

In the late 80’s I did confer with Joe Davis up at MIT/ Harvard when using fecal matter as paint for a wall mounted manadala /rondo because I wanted it to be archival and sterile. Unfortunately the artwork caught a gust and blew out of my art car one day on Allen Parkway while I was transporting it , and I kept going.

The one thing I find extremely out there is the direct experience of space felt in Judo when one is thrown. Klein was a Judoka. In order to fully understand Yves Klein it isn’t enough to use blue, and incidentally his blues were not exact each time, but it is nessesary to take a fall.

Best, Nestor.

Oh, and the folks at George H Lewis and Sons are really something else too.

Not only do they “get it” but are consumate hosts.

thanks GT for presenting this. it was the show i really wish i had not missed this year. our brown klein (< i swear to god spell check did that) friend can't but help make turbulence running down the byways backward against the current, stirring up eddies as renegade performer, spreader of brown frosting and blue paint using a judo brush and then back up the other aisle as traditional craftsman-anal-perfectionist and architect. Im always inspired, simultaneously annoyed and constantly endeared by/to this nutty fellow. No one works this hard as a dedicated artist. Im not sure why he doesn't have arthritis. and man! those icon paintings are ffff'n amazing. hiram why aren't you selling the dickens out of those?… go get em nestor.