Coatlicue Statue, Aztec, c. 1487-1521

The Exploring Latino Identities series examines issues in Latino/Latin American contemporary art through interviews with artists, art historians, and others. In this installment, Dr. Rex Koontz discusses the evolution of Latin American art from its pre-Columbian origins to today. Dr. Koontz is the Director of the University of Houston’s School of Art, and a professor of Ancient, Colonial, and Modern Latin American Art.

LMF: How has Mesoamerican identity changed through time?

RK: Linguistically and in the arts, pre-Columbian peoples would often map the world as inhabited by different classes: macehual is (Nahuatl for) working class; pilli is the noble, professional class, often warriors and priests. But when the Spanish came, that became mixed up with ideas of race: European versus indigenous. Mexicans tend to identify with the Central Highland Peoples, the Mexica/Aztecs, but the Spanish had a much harder time subduing the Maya. In fact, there were Maya cities until 1697 AD, and the Maya themselves have remained. The problem is that people don’t always wrestle with the complexity of race and ethnicity in Latin America itself. You have people who are genetically European, people who have mixed with Native Americans and/or Africans, and people who have remained largely indigenous in culture, language, ethnicity and self-identification.

Anonymous 18th century Mexican casta painting

LMF: What are some of the most important pre-Hispanic developments that shaped the artistic trajectory of the territory that we now call Mexico?

RK: China, India, Mesopotamia and Mexico are the places where cities and the act of writing were invented, so in Mexico you can draw the history of the rise of the city and the artistic complexity that grows out of that. You would start on the Gulf Coast with the first cities in the Americas, San Lorenzo and La Venta, and then Teotihuacán. For example, at Teotihuacán, by 300 AD there was an intensive mural tradition that much later Diego Rivera would cite.

LMF: How has the art-making impulse, process, ritual, and aesthetic changed from pre-Hispanic to modern times?

RK: Anita Brenner’s Idols Behind Altars: Modern Mexican Art and its Cultural Roots (1929) argued that everything in Mexico is somehow pre-Hispanic. That was during the Revolutionary reconstruction, and a lot of tourists bought into it and it became a way of thinking in the United States. It makes the indigenous people out to be superstitious, mindless in their adherence to past traditions, but the way that the indigenous world embraced Christianity and transformed it is much more interesting than that. The Colonial period is actually really interesting in terms of modern Mexico, because that’s when a lot of things were transformed recognizably into what they are now. As opposed to just being the evil Spanish destruction of the indigenous culture, it was the indigenous people appropriating and transforming Spanish culture into something that would work for them. Paz led that transformation with El laberinto de la soledad (1950), which was the first major book to say all of us Mexicans hate ourselves because we can’t be indigenous as part of the modern world, but ethnically everyone tells us we should be indigenous. One of the big reasons we are not is because of the Colonial period. Why can’t we come to terms with that?

LMF: What are the differences/similarities in how people thought about art objects then versus now?

LMF: What are the differences/similarities in how people thought about art objects then versus now?

RK: The sacred environment in which much art was experienced by the indigenous people continues, but the narrative context, the religious symbolism instantiated in that sacred context has changed. When I was living in Choquiac Cantel (near Quetzaltenango, Guatemala), the village had a mesa, a place where the whole community burns to the ancient gods in this big open area that was ringed with pre-Columbian Late Post-Classic stelae that divided the sacred space from the profane. Back in the Dirty War (1978-82), General Efraín Ríos Montt killed a bunch of people in my village. The guy I was living with in the village lived in the subway of Mexico City for 18 months because he was scared of being killed. When he came back, the Guatemalan military was still saying they were eradicating Communists. They wanted to build a helicopter landing pad on the mesa, because it was on the top of the mountain. They wanted a panopticon where they could see all of the surrounding valleys and they wanted a place where they could put down troops. Everybody on the mountain got together. It didn’t matter if you were evangélico (evangelical), or Catholic, or costumbrista, because there were still a lot of people who practiced indigenous religion. They all got together and said you cannot put a helipad on the mesa, because that’s sacred to all of us. Actually, the big evangelical preacher put a pulpit right beside the mesa, which is ironic because this is exactly what he’s preaching against, so that he could show the Guatemalan military that in fact it was sacred to him and his flock. The Guatemalan military stood down. When I got there, three of the village mesa’s stelae were stolen; they ended up in Brussels on the art market, and I recognized them. So, what the Guatemalan military couldn’t do, the art market finally did, which was to break up the mesa. That was a horrible event; it broke the sacrality of the space that was the direct relationship space to their ancestors. Most people in my village did not understand doing this for the money; that was too high a price to pay.

View out Dr. Koontz’s window, Choquiac Cantel, Guatemala, c. 1991

LMF: Does the extreme cultural shock of the conquest still resonate today? Is the phenomenon of increasing globalization a kind of mirror to this original experience?

RK: The conquest does resonate in the sense that Mexicans feel the need culturally to continually recreate their relationship to it. And that’s everyone except maybe the highest elite. And you get revitalization movements like Aztec dance and New Age religiosity that is rampant in Mexico, especially among the middle and upper class youth. I can’t see that as anything but an attempt to recalibrate their relationship with Spanish identity and the conquest. In my village, the conquest story explains the loss by the indigenous people to the Spanish in ways that are totally sacred, that have to do with supernatural powers that were not placated in the right way. That’s the way they understand the conquest, and they’ve kept that story alive for over 400 years.

Another story: my wife and I trekked 6 hours into the mountains to a little village called Cruz la Laguna. People would look at us and get scared and run away because they hadn’t seen many people who weren’t Maya. But the young people were becoming evangelical Christians left and right. If you became evangelical Christian, you could sell the santos figures on the art market. They had this beautiful church from the 16th century, and they sold everything. Because of their relationship to Catholicism, those images were then desacralized; they were biting into the evangelical thought that art objects are not right for worship. On the other hand, Polanco in Mexico City is as sophisticated and vibrant a contemporary art market as any place in the world.

LMF: Latinos in Southern California appropriated Aztec-aligned imagery during the Chicano movement, though it is uncertain whether the participating members actually had Nahua roots. Given all the changes that have occurred over time, how should/can contemporary Latin American artists relate to Latin American art history?

RK: Southern California is a great example because we know that Tlaxcaltecas, the Tlaxcalans, were the Nahuatl speakers that often moved up north because they accompanied the Spanish; the Tlaxcaltecas were their allies. So, you could do a history of who actually settled Southern California, and it could create problems for people who wanted to relate directly to the Aztecs, because they very well may be related to the indigenous group who brought the Aztecs down. And for good reason, because the Aztecs were going to bring them down. I see this recurring theme of history in Mesoamerica as a cradle of civilization: it’s very thick; it’s very complicated. What we see in the later 20th century is the desire to reach into this richness, often times by people who are distinctly marginalized and oppressed, but to use it in terms of the affirmation of a particular contemporary group. That always does violence to history, but maybe it creates a better present and future. One can point to all kinds of social goods that have come out of the Chicano Movement.

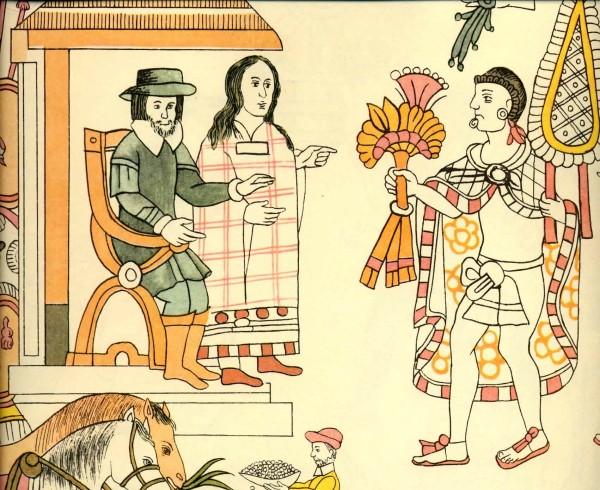

Lienzo de Tlaxcala, 1560: Meeting of Cortés, Malintzin, and Tlaxcalan noble

LMF: Is Latin American art nameable?

RK: For so long, muralism, the coherent, politically engaged, stylistically restricted movement, was what you were supposed to do as a Latin American artist, just like what you’re supposed to do as a Parisian artist is to be avant-garde and a little bohemian. There are these categories in which others view you and it’s easy for you to then, because you want success, bend yourself to their preconceptions. With the rise of Gabriel Orozco, and even for the last 20 or 30 years, we’ve seen that identity of Latin American art come apart. It took a long time, because Latin American artists have been talking about how this wasn’t how they wanted to be defined since the 1950s.

Gabriel Orozco, Cats and Watermelons, 1992

LMF: So, for the contemporary artist, is there a disconnect from history?

RK: I think there is less of a necessity to position yourself in a particular historical way. That doesn’t mean that you’re not thinking about history, but you—as a human being, as a creative artist—do not need to be x, y, and z as a Latin American artist. I think the idea of a Latin American artist has grown much wider to the benefit of the entire world’s art community. But you’ve lost something there: you’ve lost that engagement with a sometimes tragic, always complicated, very rich past that Latin Americans positioned themselves with from the Mexican Revolution through the Argentine dictatorship.

LMF: What is the function of UH as an institution in relation to the Latino community?

RK: We have an enormous Latino population both inside the university and out, we have the most aggressive collecting institution of Latin American visual culture in the world outside of Latin America itself (the MFAH), important commercial galleries, and some of the most important collectors in North America. Outside of the stratospheric economic context of the art world, we also have a lot of people in our community with relationships to art traditions that are perhaps not that tied to contemporary art world traditions. For all of those things, UH can serve as a node, not so much to drive thinking one way or the other; I’m a little wary of creating a think tank in which a dogma is projected of the way you should be thinking about yourself if you’re a Latin American who creates, but I do think we can be a house of experience where you can get together with everybody else. You can have that part of you taken very seriously. Even if this is something not directly related to you, this is something as a Houstonian you need to know about. This is something that can be that part of your artistic sensibility that a lot of people are not going to get in other cities, and that’s a good thing. There’s no reason to limit that to ethnic identities.

Dr. Koontz’s recent books include Lightning Gods and Feathered Serpents: The Public Sculpture of El Tajin and Blood and Beauty: Organized Violence in the Art and Archaeology of Mesoamerica and Central America. He has done fieldwork in Mexico, Guatemala, and Honduras under the aegis of the Tinker Foundation, the University Research Council of the University of Texas, and the National Endowment for the Humanities, among others.

6 comments

I’m digging this series.

I loved this article. Dr. Koontz very knowledgeable and eloquent. It reminded me of my MFA days.

Oh dear,

I clicked before I could correct the spelling!

Fixed it, Loli!

I always enjoyed listening to Dr. Koontz lectures on Latin American Art. This article on Exploring Latino Identities reminds me of those days, as a student in his classes. He was and is very knowledgeable.

Great education article for me.

Thanks.

Marijane Stomberg