In honor of our conversation between Catherine Opie and Eileen Myles in Houston this Saturday, April 29th, 2017, we present this two-part series on the landmark works of Opie, a photographer, and Myles, a poet and author. Part One features some of Opie’s iconic works. Part Two, here, is an introduction to Myles. (Click here for tickets to the talk!)

The thing about not being historically a mainstream writer is that everyone feels like you’re theirs: you’re their friend.

-Eileen Myles

Glasstire wanted and secured Catherine Opie for its next Off Road artist conversation, and when it came up that Opie’s Houston talk could be with her longtime friend, the author Eileen Myles, the anticipation for the event immediately doubled, like a small explosion happened at the office. These two talking. How cool would that be?

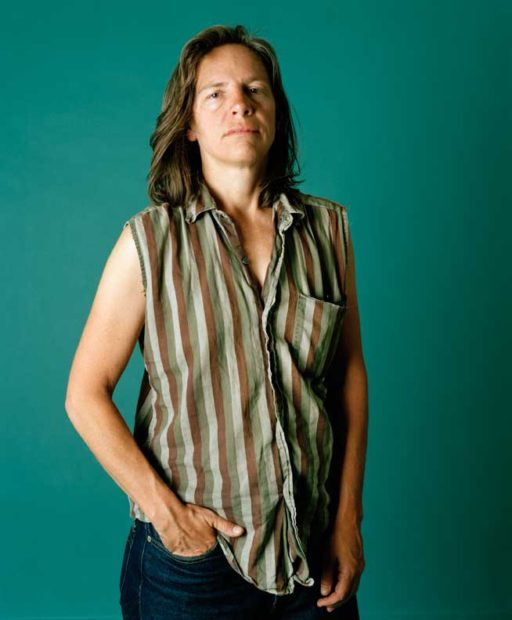

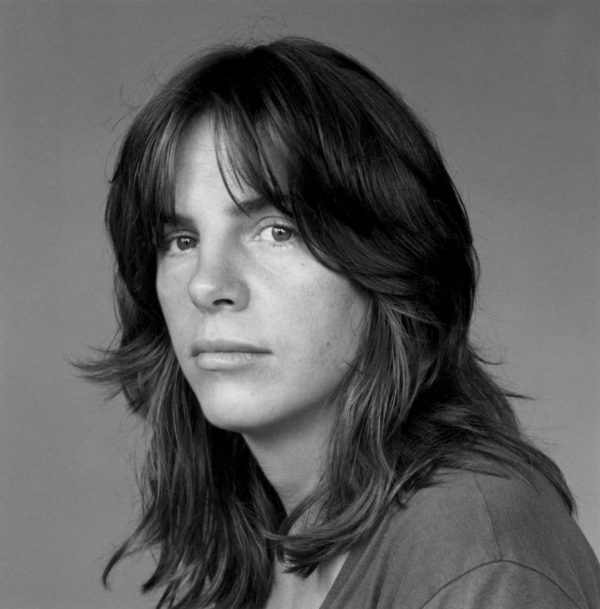

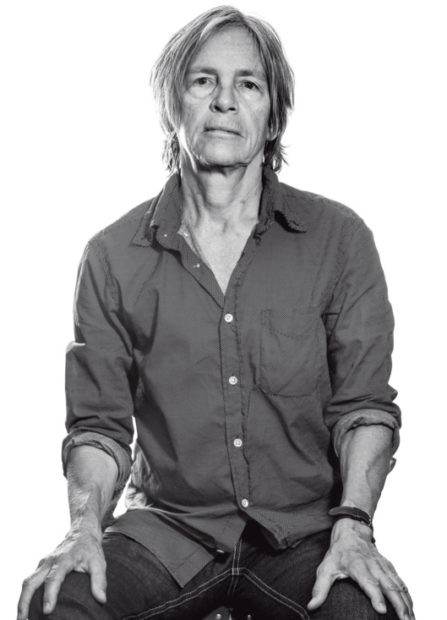

Myles does write about art, sometimes (and brilliantly and unconventionally), but Myles is best known as a poet, storyteller and novelist, a sharp and rangey dyke with a fanatical following and an almost mythological living presence in the world that most of us think of as “literature” (a word Myles has dismissed as a bit archaic). Written about with almost alarming frequency in pages like the New York Times, the New Yorker, the Paris Review, and the New York Review of Books, Myles is a cult figure whose cult is so big now that, among literary types and pop-culture hounds, you can just say “Eileen Myles” and people of several generations nod appreciatively.

There are a number of reasons Myles has taken up a spot on the front lines of recognizability in recent years. One is that they (Myles prefers non-gendered pronouns for themselves) are active and working constantly and the work is so accessible now via the Internet; one is that the brilliant streaming series Transparent based a particularly seductive and charismatic character on Myles in 2015 (the critic Ken Tucker tweeted: “The best thing @transparent_tv has done is made more people aware of @EileenMyles”); one is that if a gifted writer works long and hard enough and stays the course, the work becomes canon.

This was helped along by the 2016 reissue of Myles’ 1994 collection of autobiographical stories Chelsea Girls, which knocked Patti Smith’s book Just Kids off of the throne of downtown New York cool storytelling, as a new generation of readers dug in. And Chelsea Girls is a fantastic distillation of Myles’ strength as a storyteller. In the writing, Myles notices the small things and describes intimate or humiliating or erotic or harrowing moments with a kind of casual truth that can stun. Myles’ language feels informal and even conversational yet, they’re putting down something completely new—a completely new way of describing a familiar thing. When you read the prose or poetry you are hearing Myles’ voice so distinctly that it’s as though Myles is sitting next to you on the bench and telling you something. The manner can seem tossed-off but it’s actually incredibly precise, and the content is fascinating and sticky. Drugs, sex, poverty, hope, death, much of it in the 1970s and ‘80s. (The New York Times: “She seems to have done an impossibly enormous amount of living.”) The timelessness and power of these stories is especially poignant right now, as the past—the way we lived and were more present in the past—is looking more irresistible and romantic in the face of our current realities and disconnections.

Last year, in the New York Review of Books, Dan Chiasson wrote of Myles:

“…Myles’s poems set a bar for openness, frankness, and variability few lives could ever match; and so in her work, the surprise second life is actually the one lived off the page, refracted through decades of Myles’s astonishingly vivid lines.

Her poems are chronicles of barriers first feared, then crossed, and of the physical and sensual pleasures and pains that followed.

Myles’s work has always been uncompromisingly frontal, a face-forward presentation of herself, simultaneously vulnerable and scrutinizing. If you look at her, she looks back.”

Born in Cambridge, Myles attended UMass in Boston and then moved to New York in 1974. Myles has published more than 20 books of poetry and prose, is a recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship, was the artistic director of St. Mark’s Poetry Project for 20 years, was the director of the writing program at University of California, San Diego for five years, and now teaches writing at Bard, Columbia, NYU, Naropa University, and other institutions. Myles has been a fixture on the New York downtown avant-garde writing and art scene since the mid-‘70s, and seems to know (really know) every famous and infamous artist, writer and musician associated with that supernova era. Their name could be a synonym for “East Village,” though they’ve got a place in Marfa as well these days. Myles cuts the figure of a real Marlboro Man—impossibly cool and supremely rock-and-roll.

Myles’ connection the art world is direct, personal, and refreshingly non-academic. They’ve said that upon getting sober years ago, one surefire way to still get high was to go look at art, and Myles’ encounters with art has led to some of the most direct and intuitive art writing of any generation. Myles received the Clark Prize for Excellence in Arts Writing in 2015. It’s as though they can stroll through a show and their antennae picks up on the small but crucial details in and around the work itself—the kinds of things so often overlooked by insiders who are too invested in the correct way to respond to something. Here Myles is on Nicole Eisenman, reprinted in their collection of art essays The Importance of Being Iceland: Travel Essays in Art:

“When she did show up, moments before the opening’s end, she looked a little removed—saying hello to people but not entirely there. She wore a black shirt, her hair was kind of Wildean and awkwardly she was carrying a red rose. The rose was perfect. I don’t know if her girlfriend gave it to her, or what, but that rose was so like her arrival out of a cab in a black shirt, looking exceedingly pale—the flower was thin and dark and thorny. That rose was pure punk. I could go on but I won’t. Nights don’t end, they fall apart.”

But if you really want to get a quick, hard hit of Myles’ work and voice prior to Saturday’s conversation, a way to mainline their work is through the poetry. Published and acclaimed collections include Maxfield Parrish: Early and New Poems, and I Must Be Living Twice: New and Selected Poems 1975-2014.

Following are two of Myles’ best known poems, the first being On the Death of Robert Lowell (of which Chiasson in the New York Review of Books wrote: “Myles is sometimes misunderstood on the basis of a single poem, which depressingly keeps cropping up in reviews of these volumes—mine, alas, being no exception. On the Death of Robert Lowell is her blurted, blasphemous, punk, and utterly Bostonian elegy for Lowell.”)

O, I don’t give a shit.

He was an old white-haired man

Insensate beyond belief and

Filled with much anxiety about his imagined

Pain. Not that I’d know

I hate fucking wasps.

The guy was a loon.

Signed up for Spring Semester at MacLeans

A really lush retreat among pines and

Hippy attendants. Ray Charles also

once rested there.

So did James Taylor…

The famous, as we know, are nuts.

Take Robert Lowell.

The old white-haired coot.

Fucking dead.

And here is a understandable favorite of Myles’ loyal readers, titled Peanut Butter, from 1991.

I am always hungry

& wanting to have

sex. This is a fact.

If you get right

down to it the new

unprocessed peanut

butter is no damn

good & you should

buy it in a jar as

always in the

largest supermarket

you know. And

I am an enemy

of change, as

you know. All

the things I

embrace as new

are in

fact old things,

re-released: swimming,

the sensation of

being dirty in

body and mind

summer as a

time to do

nothing and make

no money. Prayer

as a last re-

sort. Pleasure

as a means,

and then a

means again

with no ends

in sight. I am

absolutely in opposition

to all kinds of

goals. I have

no desire to know

where this, anything

is getting me.

When the water

boils I get

a cup of tea.

Accidentally I

read all the

works of Proust.

It was summer

I was there

so was he. I

write because

I would like

to be used for

years after

my death. Not

only my body

will be compost

but the thoughts

I left during

my life. During

my life I was

a woman with

hazel eyes. Out

the window

is a crooked

silo. Parts

of your

body I think

of as stripes

which I have

learned to

love along. We

swim naked

in ponds &

I write be-

hind your

back. My thoughts

about you are

not exactly

forbidden, but

exalted because

they are useless,

not intended

to get you

because I have

you & you love

me. It’s more

like a playground

where I play

with my reflection

of you until

you come back

and into the

real you I

get to sink

my teeth. With

you I know how

to relax. &

so I work

behind your

back. Which

is lovely.

Nature

is out of control

you tell me &

that’s what’s so

good about

it. I’m immoderately

in love with you,

knocked out by

all your new

white hair

why shouldn’t

something

I have always

known be the

very best there

is. I love

you from my

childhood,

starting back

there when

one day was

just like the

rest, random

growth and

breezes, constant

love, a sand-

wich in the

middle of

day,

a tiny step

in the vastly

conventional

path of

the Sun. I

squint. I

wink. I

take the

ride.