DP92, the newest performance by Dead White Zombies at The Icehouse in Dallas purports to be homage to those beloved, under-financed, overly paranoid sci-fi thrillers out of the 1950s. But the plot has more in common with trippy, psychological concepts in Pink Floyd albums and rock operas by The Who. Heavy Metal magazine is probably more of an influence on the costumes and set design than those relatively chaste matinee pictures. I’m grateful that rock ’n’ roll wins out over geekdom in this case. Let’s revel in few of the show’s details: Lots of skin showing through ripped or open clothing; tight body suits; youthful vigor in combat boots; contact and writhing; the upsetting of authority; backup singers; and one hell of an improvised guitar, the body of which is an amplifier. The show is high-concept and high-energy, a kind of stadium rock for the thinking person, carried out with poetry, gesture, a Franken-guitar, and a theremin.

Dead White Zombies was founded in 2011 by Thomas Ricccio, Lori McCarty and Brad Hennigan. Their work draws from Riccio’s extensive research in the area of indigenous ritual. He has developed performances in Africa, Siberia, Korea, China, Vietnam, and Alaska. In a previous article about his work I wrote that, as shot-caller for the Zombies, “Riccio puts the pedagogy of mythology and anthropology right on the line of Dallas culture, blending the politics, pastimes and social structures of the city with the cosmology of classical paganism (Homer, Virgil, Ovid) and a variety of shamanistic traditions, both ancient and contemporary.”

DP92 draws more from shamanism than it does from pedagogy. Press materials call this performance a work of “immersive theater,” which is a trendy term for ritual. The Zombies are specifically interested in bodily rituals, which are a more free-wheeling form of spiritualism that the text-based meditations and consecrated liturgies of the major religions. Bodily rituals treat sensory, motor, and affective capacities as a unified field; the constant interaction and modification on the part of all the senses articulates the world into an intelligible and renewable concept of life and its meaning. DP92 is not a religious work in the sense that it presents a specific testimony to the origin of life (and not to mention, rock ‘n’ roll and sci-fi are its chief sensuous aspects!). But it is a bodily engagement, in the form of a walking tour, with unusual objects and myriad associations that invite an altered or spiritual state of perception.

The performance begins with a form of triage. The audience has been milling around in a lobby/holding area when all at once we’re invaded by a risibly self-important group of doctors in lab coats. They fan out and question audience members with an expediency that borders on aggression. People who arrived as couples or in groups are quickly separated. It’s interesting to watch people lie, to deny knowing one another so that they can stay together. The doctors are onto them, though, and everybody goes into groups with strangers. (When I was questioned, I said, truthfully, that I’d come alone. That drew more suspicion from my inquisitor than if I’d lied about being part of a group.) Once inside the performance space, all the groups split off to observe different chambers in the space.

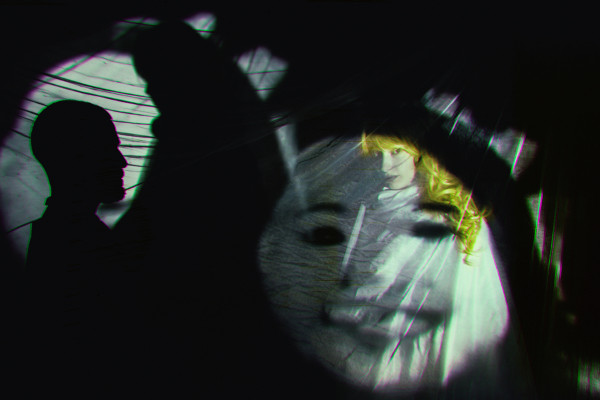

Moving through the different areas is how one picks up pieces of the plot. I wasn’t treated as an audience member but as a kind of refugee being shown the ropes at this industrial space, which was to be my new home. Some vague but horrible tragedy had occurred outside and I was told how lucky I was to have made it there. My given name would be useless under these dire circumstances and so I had been given a number to wear around my neck. In addition to being a refugee, I was something of a test subject, because in this world, all the performers wearing numbers exhibited signs of distress or mental differences. These problems may have started with the bad conditions outside, but they were exacerbated by the studies and monitoring within. I learned that no one is trusted inside the center; daily life is pretty tense. The one grace note for the inmates is DP92, a heroic young woman who managed to escape monitoring and is now running around somewhere within the center, gumming up the works when she can.

Looming powerfully and inscrutably over the chaos going on outside is the Mollusk Mind. It’s a god that no one is quite sure whether to propitiate to or flee from. But one thing is certain: the god is drawing closer to the center. Its arrival could be the end times or a new beginning. The tension surrounding its arrival quashes the bullying certainty of the doctors. They stop barking orders and start asking themselves serious questions about selfhood, lifespan, and legacy. Presently, the doctors surrender the notion of authority. The phrase “Come with me” loses its sharpness and becomes a request, almost a plea. It’s as though the doctors want a witness to their struggles—someone who, just by being present, will dignify their endeavors in a crumbling situation. As for the inmates, their speeches evolve from lamentations to thoughtful searches for renewal and connection, ways in which to live a good life in bad times.

This leveling experience between the doctors and the inmates is the focus of the performance. Tragedy or a sublime experience can draw people closer together. Over the course of the show, as boundaries deteriorated, I found myself touring the performance with different groups: all the old arrangements had been discarded. This loosening of structures wasn’t chaos; it was, rather, the performance building toward unity.

When we meet the Mollusk Mind, it has fused with the rogue hero DP92. The result is a striking female form in silver body suit with outrageous growths of viscous mollusk skin on her head and vagina-like valves on her back. She’s a poetic creature, lyrical and blind. Pious inmates glory at her spiritual non-sequiturs while helping her not trip over anything. She’s an otherworldly presence in an innocent, inchoate form, kind of like the baby Jesus or Leeloo, the cosmic wonder that Milla Jovovich played in the movie “The Fifth Element.” Her helplessness is a vital part of the awe she inspires in the other players.

Dialogue in DP92 is, as it is in every Zombies show, more of an artful construction than it is a delivery device for information. Language is explored for its rhythms and its mysteries. Characters speak a mix of poetry, academic construction, and private epiphany. Somehow ideas come across and necessary plot points are expressed. But most of all the language, no matter how many currents of philosophy a character might be chasing, is presented as a chant to invite a robust meditation.

The Zombies don’t truck with quietness and nothingness. Their focus is an energetic maximizing of eternal “somethingness.” The language compliments the dynamic sensuousness of the stage design and makes moving through it seem like a vital ritual. The words spoken at the end by players and audience members alike put a crown on a beautiful, well-crafted ceremony that closes the performance. In a unifying, liturgical act, our identifying numbers are lifted away and each of us rediscovers our own name. The Age of the Mollusk has ascended and we are all part of its evolution. What a trip!

DP92 is written and directed by Thomas Riccio and features Alia Tavakolian, Bailee Rayle, Ilknur Ozgur, Hillary Holsenback, Abel Flores, Hannah Weir, Joshua Kumler, Brad Hennigan, Adnan Nassem Khan, Stephanie Oustalet, Rebecca McDonald, Shelby Hibbs, and Alexandra Werle as DP92. Performances run through November 22 at The Icehouse, 2516 N. Beckley Avenue, Dallas, 75208. Info and tickets: www.deadwhitezombies.com.

2 comments

Thanks, Richard, for this excellent review of a complex experience. This was my first Zombies show. I was impressed by the actors’ physical commitment and ability to create characters within a context that could have become abstract sludge. That said, I did think that after an hour or so the work was being done in by the onslaught of language. I found myself tuning out. I wish Riccio and company would explore silence in an upcoming production. I also wonder why so much of the experimental theater I have seen since the 1960’s has to involve writhing? Can dialog delivered while writhing ever not come off as unintentionally silly?

Law I would like to see: anyone who indulges in zombie mania/ buys zombie-themed gear/ etc. who hasn’t read Max “Son of Mel” Brooks’ “Zombie Survival Guide” and “WWZ” (the movie sucked, the book is an incredible tribute to Terkel’s “The Good War”) should be flogged. If you haven’t read Brooks’ books – which are about being unprepared for predictable disasters like AIDS, Ebola, and Hurricane Katrina – you just don’t get it.