Jem Cohen comes from a particularly creative household. His mother was writer Miriam Grossman, the author of more than 20 children’s books, and his father, Monroe D. Cohen, was a painter and academic. Before Cohen was born, his mother had been in a relationship with photographer Sid Grossman; subsequently, during his childhood, Cohen was steeped in the traditions of New York street photography. Consider also that Cohen is a close childhood friend of Ian Mackaye, guitarist and singer for Fugazi and Minor Threat and founder of the legendary Dischord Records label, and you begin to get a sense of how one of cinema’s most distinctive voices was formed.

Cohen’s filmography of more than 70 works blurs the line between the “fine art” of galleries and museums and the accessibility of a punk rock concert. His films are collected by the Museum of Modern Art and have been distributed theatrically in more than 100 cities across the world.

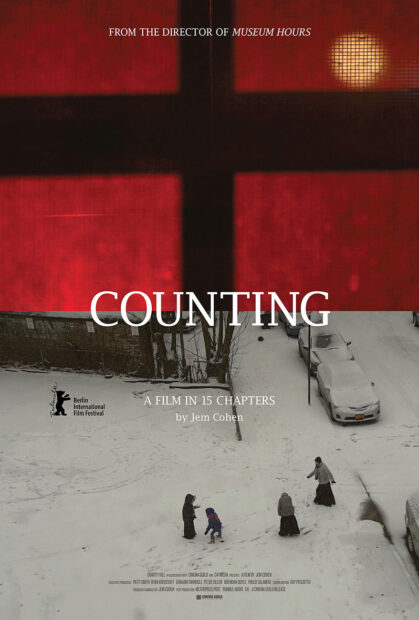

On April 7, the Texas Theatre in Dallas will host Cohen for a 25th anniversary screening of Instrument (1999), the filmmaker’s debut feature film on seminal Washington, D.C. band Fugazi. The theatre will also host an April 6 screening of Museum Hours (2012), the award-winning fictionalized meditation on the life of a museum guard in Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum. Cohen will be in attendance for a Q&A after each screening.

I spoke with Cohen ahead of the screenings to discuss topics ranging from early 20th century Dada collage to his Texas connections and the relationship between Willie Nelson and Phillip Guston.

Michael Flanagan (MF): The Messthetics, a band featuring Joe Lally and Brendan Canty of Fugazi, recently released a new record on the Impulse! Records label, which has also released music by the likes of Ray Charles and John Coltrane. I was struck by the fact that there is now a throughline from the early days of Washington, D.C. punk rock to one of the most prestigious jazz record labels of all time. You grew up documenting that Washington, D.C. scene and, similarly, your films are now in the collections of major institutions. Why do you think the work has connected with people in such a significant way?

Jem Cohen (JC): I wasn’t thinking of my high school buddies as people who are going to be famous. I was going to see them in garages when somebody’s parents were away for a weekend — 35 people would show up and they’d just be thrilled with it.

I didn’t play an instrument, so I was just starting to take photographs and occasionally make a flyer. The beauty of that whole time was the sense of discovery and excitement — a total commitment that you felt that was bubbling up in many different places.

One day at my high school, a station wagon pulls up with [Washington, D.C. band] the Bad Brains in it and they’re handing out their single. That’s how I got that amazing “Pay to Cum” Bad Brains single — It was handed out for free from the back of the station wagon. At the time, you’re not thinking that this is a legendary moment. You’re just running after the station wagon.

I also had my early awkward feelings of being an outsider. I was not one of the diehard kids who would get in the van and roadie for Black Flag. That’s what some of my friends were doing when I went off to college. I was heading towards filmmaking.

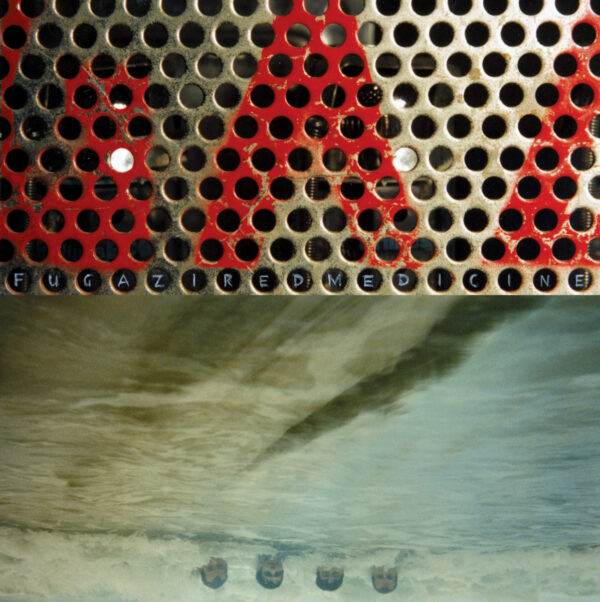

MF: While you are well-known for directing Instrument, your 1999 film documenting Fugazi, you also collaborated with the band to design album artwork for several records. How did you come into that role?

JC: The band was so focused on making the music that they didn’t really have time to perfect a visual realm that correlated in a fair way to their music. I saw that as something that I could attend to and redress. I ended up doing four sleeve designs for the band. Those were certainly collaborative projects to a degree. They were often done when I was visiting the band in the studio while they were working on a record, and maybe documenting that for Instrument at the same time. I’m very proud of my visual work with Fugazi. A lot of people don’t know that side of me.

MF: In addition to those record covers, the designs for your films also have a distinct look.

JC: It’s all collage work, really. I recognized from early on a way in which I could approach any media — whether it was a record cover or a movie — through bringing together disparate elements in some kind of odd conjunction.

That has been a constant in terms of aesthetics for me, and that goes back a long way. I grew up knowing the work of John Heartfield, for example, who was a radical German collage artist in the 1920s, ‘30s and ‘40s.

You had to make stuff without money and resources and one of the ways to do that was to gather a bunch of scraps together. And that’s what Instrument certainly is. It’s what all the movies are, including Museum Hours. Half of the movie is me wandering in a city and gathering shots in a very unscripted way, and then I’m dropping actors into unpermitted situations where the world is not necessarily aware that a movie is being made.

I love the fact that the Texas Theatre is showing Instrument and Museum Hours. It’s very enriching that the same people will be able to see both movies and search out commonalities, because they’re actually there.

MF: What is your relationship with Texas?

JC: When it came to Texas early on, it was such a thrill to hear these rumors about groups like the Butthole Surfers, Big Boys, and the Dicks. The unlikeliness of it was mind boggling. How could that be happening in Texas? Because we had a certain romantic notion of what the state was like.

The other thing is that my father trained at Rice University. So I grew up hearing about Texas with my father listening to country western music. Later, Willie Nelson became tremendously important to me. He’s kind of a hippie singing about karma — very poetic and smoking his weed — in a way that correlated with a punk spirit. I also became more familiar with the Lubbock scene and started listening to records by Terry Allen. Once again, they were breaking the mold of whatever one might think of as a stereotype of country music or of Texas.

MF: In addition to your connections to Texas through your father, you’ve had the occasion to work on several of your own projects here over the years. You shot a portion of your 2004 film Chain in Dallas, and collaborated with minimalist composer Terry Riley in Austin. Can you talk about those experiences?

JC: Another throughline for me is Bart Weiss and the Dallas Video Festival. You look back at the very early days and here’s this guy in Dallas who really cares about the fringy, weird, and independent stuff. He’s one of those people who consistently supported and shared my work. I was in Dallas attending the festival and ended up shooting some parts of Chain while there.

I also did a gig with Terry Riley that’s very precious to me. We did this show together with Cinematexas in Austin, where I projected 16mm films inside of a church. Terry had no interest in playing to the screen — he came from a much more Cageian universe where these things would coincide and collide in mysterious ways. I wanted to be able to alter what I was doing organically with what Terry was playing, so I asked for modified projectors that would allow me to change the speeds. We were both very freaked out about the Gulf War, so I incorporated a reading that I had recorded of the names of U.S. soldiers and Iraqi civilians killed in that useless, stupid war.

MF: You have produced several artist portraits, including Anne Truit, Working (2009) and the recently completed Ballad of Phillip Guston (2022). How does the throughline of your creative influence move from Bad Brains and Willie Nelson to Anne Truit and Phillip Guston?

JC: It seems chaotic or disjointed to hear the list, but to me it isn’t because they’re all renegades who absolutely prioritized art making as a non-commercial enterprise. There’s a commonality to me in responding to work done by people who are clearly doing it out of some deep necessity that is not about getting famous or making money.

That’s very important to me, and it’s increasingly seen as old fashioned or out of time because we live in such a different moment in which everything is about monetizing side hustles, self-promotion, and social media, which in a lot of ways is inherently antithetical to a certain other kind of creative endeavor.

MF: What do you see as some of the most significant challenges facing artists in 2024?

JC: It’s harder to make a living and it’s harder for the unusual movies to find their way in the world. None of us could ever have envisioned the degree to which a very few, very wealthy entities are really controlling what we see, read, and experience. If we get Trump as the president, then we will see a diminishment of arts, independent media, and actual news gathering and dissemination. We will see a decimation of that, which we can barely even conceive of.

MF: It brings to mind the idea of degenerate art that was formed in Germany during the 1930’s.

JC: Yeah, well that’s a very important history to reflect on. We have to realize that it absolutely can happen again. There’s already terrible censorship of books and ideas going on. We are heading towards some very serious reckoning about what matters to us as a country.

MF: What themes are you exploring in your current work?

JC: I’m just wrapping up what I consider to be the sister film to Museum Hours. It’s about an older astronomer whose wife is a physicist and how scientists are navigating the landscape of the world that we live in now.

Let me bring it back one more time to Texas — I had a gig in Marfa where I wanted to go shoot at the McDonald Observatory. That was a very beautiful experience, but there are concerns there about losing the dark skies the observatory depends on to the oil facilities that shine very bright lights.

You think you can get away from politics, but if you want to look at the night sky, you’ve got to realize that there are politics involved with whether or not you’re going to be able to see stars anymore. I don’t like to make movies that are propagandistic, but I can’t do work that doesn’t somehow try to engage with these issues. The movie’s called Little, Big, and Far.

MF: The Entre Film Center in Harlingen will host a screening of Chain on May 23. Can you expand on the themes of cultural homogenization that are present in that film?

JC: I was thinking primarily about the homogenization of landscape. I was exploring the world in which regional character was erased and replaced by a corporate homogeneity, which has powerful repercussions beyond just the fact that airports, highways, and fast food restaurants have increasingly made it so that every city looks largely the same.

I decided to take that on in some way and ended up making a narrative documentary hybrid with two women characters. A Japanese businesswoman, and then a kind of drifter who, as a matter of survival, moves into a shopping mall for much of her time.

It’s funny, because it brings me back around to Hank Williams. I love that song, “Ramblin’ Man.” It’s probably my favorite Hank Williams song. It got stuck in my mind — how does a ramblin’ man deal with a geography where everything starts to look exactly the same? You can’t really ramble when you’re just moving from one Walmart to another.

Visit the Texas Theatre online for tickets to the April 6 and April 7 screenings of Museum Hours and Instrument. Follow ENTRE Film Center for more details on the May 23rd screening of Chain. More information on Jem Cohen is available at jemcohenfilms.com.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MqctCwhunjE