Para leer este artículo en español, por favor vaya aquí. To read this article in Spanish, please go here.

Title wall of the exhibition “Japan Form and Function: The Montgomery Collection,” on view at the Crow Museum of Asian Art

I have a confession: for a long time, I firmly believed that function was incompatible with, or counter to, the pursuit of “pure art.” In other words, that real meaning in art was hindered by secondary aims like functionality or practicality of any sort. This led me to underestimate disciplines I considered (I blush) second rate, like architecture, ceramics and textile work, as opposed to the purity of music, literature and painting. But through experience and a more ample knowledge of art history, I have been long disabused of that notion. Today I can say, as a recovering “purist,” that deep meaning and profound beauty can frequently be found in what I had previously dismissed as “folk art.” This is evidenced by the new exhibition, Japan, Form and Function: The Montgomery Collection, currently on view at the Crow Museum of Asian Art in Dallas.

For this compelling show, curated by young Swiss scholar Luigi Zeni, the entire museum’s gallery space has been devoted to showcasing more than 240 objects from different periods of Japan’s illustrious history of craftsmanship, spanning the Neolithic age all the way to the 20th century Mingei Movement. It includes stoneware, earthenware, and porcelain, but also woodwork, bronzes, and painted textiles. The show contains pieces from all regions of Japan, focusing on the six ancient kilns, or rokkoyo — a term coined by artist Fujio Koyama to characterize the most emblematic ceramic centers of the island. These objects represent a fraction of Jeffrey Montgomery’s art collection (the biggest collection of Japanese folk art outside of Japan), but more importantly, they are a testament to his long-lasting love of Japanese handiwork, which began back in the 1950’s.

Installation view of the exhibition “Japan Form and Function: The Montgomery Collection,” on view at the Crow Museum of Asian Art

In the first-floor galleries one can enjoy lacquered cabinets and katana holders, along with portable sake flasks with flower designs from Okinawa, and later on, plates, bowls, and jars from the Kyūshū region, dating from the 17th to the 19th century. As one moves around the galleries, distinctive patterns of decoration can be observed, like the pine branch, grass, and butterflies; or abstract ones like the combed brushstrokes achieved through the trailed glaze technique.

It is impossible to view this exhibit without thinking about Wabi-Sabi, a Japanese aesthetic centered on the acceptance of imperfection and transience in art. It is the idea that flaws in an object can be beautiful, and can even highlight the general beauty of a composition. The coat of many of these objects is both rustic and refined: irregularities and asymmetries are the signs of the human hand, and the uncertain nature of ceramic firing reveals itself on the surface of the object. One has to look closer to appreciate these peculiarities. Smoothness and perfection are not human; absolute symmetry is a platonic concept never really found in nature.

Mannequins have no skin, mechanically reproduced utensils have no heart. But here, despite the limits set by functionality and the collective workshops that produced these pieces, no object is the same. Just as a minor imperfection in a beautiful human face (thus called a beauty mark) underscores harmony, a slight crookedness or a barely perceptible asymmetry or an irregular stain in the glazing makes these bottles, bowls, and plates that much more sublime.

Beauty is Not in the Eyes of the Beholder

On my first visit to the exhibition, I had the good fortune to attend a tour lead by the show´s curator, Luigi P. Zeni, for which Jeffrey Montgomery was also present. Zeni spoke eloquently about key concepts relative to the philosophy and history behind Japanese handicrafts and described some objects from the exhibition, most of which were created in collaboration by anonymous masters many centuries ago.

Jars by Murata-Gen, 1904-1988, Shōwa period, ca.1960. On view in “Japan Form and Function: The Montgomery Collection” at the Crow Museum of Asian Art.

In a wonderfully decorated gallery on the second floor, we found ourselves contemplating a massive storage jar (stubo) of quite irregular shape from the 12th century CE. While Zeni was explaining some technical aspects regarding the firing process and glazing techniques known at the time, I asked, “As a person educated in western art history, I can’t help thinking about European medieval painting and sculpture when I look at this piece. Is it fair to say that at this point the artists were still trying to learn a new technique and that explains the irregularities and awkward shape of this jar?” Standing in the back, leaning on his cane, Montgomery chimed in: “Well, for the Japanese, there is no concept of ‘better’ or ‘worse’ in art, good or bad technique, or the idea of progress as we understand it.”

Although abstruse, the answer coincided with what I had found in Sōetsu Yanagi´s The Unknown Crafstman, a classic text on the tenets of the Mingei Movement. Duality between perfection and imperfection belongs to a Greek concept of aesthetics, Yanagi says; a platonic distinction we take for granted in western traditions. In the Zen Buddhist approach, true eternal beauty resides in a plane previous to these dichotomies and categories which — to the Eastern sensibility — simply feel too intellectual. We then must renounce thinking in terms of “good” and “bad” art, perfection and imperfection, beauty or ugliness. For the Zen Buddhist, the key to fulfillment in art (and life) is not technical superiority or creative genius, but lack of attachment.

This can be uncomfortable for a western mind. Questions follow: how, then, to select an object to exhibit? How do you go about collecting and appreciating something without making the distinction between good and not as good? What are the criteria of selection? Isn’t the contradiction too great? Well, contradiction, as you may know, is the hallmark of mystical Eastern thought. As written in the Tao Te Ching:

If you want to become whole, let yourself be partial. If you want to become straight, let yourself be crooked. If you want to become full, let yourself be empty. If you want to be reborn, let yourself die.

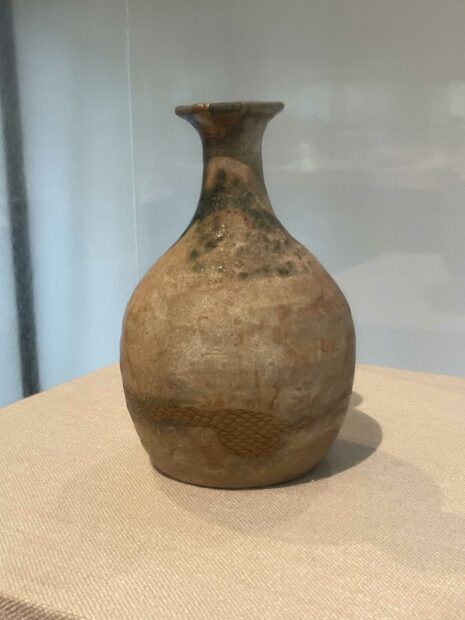

Sake-Bottle (tokkuri) with golden repair (kintsugi), Muromachi period, 16th century Seto ware, glazed stoneware and golden lacquer, on view in “Japan Form and Function: The Montgomery Collection” at the Crow Museum of Asian Art.

This exhibit pushes us to embrace the contradictory. But it doesn’t stop there, as “good” and “bad” are not the only ideas eschewed by the Japanese artistic tradition. Concepts such as “substance” and “originality” are central to western art history. We think of artists’ lives and art movements as heroic narratives, with a beginning, an apotheosis, and a period of decadence. First there was the archaic, then the classical, and finally the Hellenistic period of Greek sculpture. We speak in terms of early and high Renaissance, lamenting the excesses of the Baroque and the Rococo.

This vision does not fit the Eastern way of thinking about art making. According to Sōetsu Yanagi, the beauty of Japanese craft is not a transcendental accomplishment. Instead, it is based in the very abandonment of the aspiration of transcendence. The unknown craftsman is not trying to tap into the substance of things, because instead he is subsumed by the here and now. In the east, real creative freedom is not understood as free expression and the affirmation of one’s individuality. Real freedom consists in liberating oneself from individuality altogether.

The reason craftworks in the Japanese tradition have a claim to such accomplishment, paradoxically, is that they rely heavily on tradition and rules, allowing the hand of the artisan to be free of any affectation of transcendence, thus liberating it from the hindrance of the heroic impulse. The artists created objects of a beauty that is not the opposite of ugliness, but a manifestation of the independence from desire.

Despite the rejection of individuality, the hand and the heart of the unknown artisan can still be noticed in pieces like a sake container (funadokkuri) from the Momoyama period, or a sake bottle (tokkuri) with a golden repair (kintsugi) of the Muromachi period — works that somehow evoke both innocence and maturity.

Installation view of the exhibition “Japan Form and Function: The Montgomery Collection,” on view at the Crow Museum of Asian Art

Mingei

Mingei means “art of the people,” but is also the name of a revival movement, as well as a fluid style of ceramic making. It is additionally a way of thinking about art. It was born as a reaction to Japan’s opening to the west in the 19th century and the wave of cheap industrial goods that had flooded the country by the first half of the 20th century.

Yanagi and other artist-collectors set out to define Mingei, but not in an analytical manner; instead they tried to capture the spirit of handmade objects made for everyday rituals by anonymous masters. They opposed the conformity of mechanically-reproduced objects and tried to recapture the “aura” of the selfless craftsmen and women from the old Japanese workshops and kilns.

Installation view of the exhibition “Japan Form and Function: The Montgomery Collection,” on view at the Crow Museum of Asian Art

Herein lies another paradox: Mingei artists like Yanagi, Rosanjin, Shimaoka or Leach, started to produce magnificent ceramic works that aimed to achieve timelessness and traditional beauty, yet, at the same time are modern, specific and individual.

Being here at the Crow and enjoying the calm ecstasy that this show can provide, I cannot help but admire the contrast between Eastern and Western ways of being. On one side thusness (being in the moment), and on the other, metaphysics (transcending the moment). But at the end of the day, regardless of our origin, we cannot help our love for beautiful objects, not just in a materialistic sense, but because of the meaning imbued in them by the human hand of our global ancestors. I look at the buddhas, flower depictions, cats, and other carved animals on the second floor. I admire the beautiful banner with scenes of the battle of Imjin River, and they move me. So too do the robes and little statues of birds, rabbits, and bears placed at the end of the show. The duality between East and West is, in the end, as superficial as the duality between intellect and instinct, or between left and right.

Storage jar (tsubo), Heian period, 12th century Tokoname ware clay with green glaze with fragments of ash, on view in “Japan Form and Function: The Montgomery Collection” at the Crow Museum of Asian Art.

I’ll end with a second confession: as I leave the exhibit, the problem of beauty haunts me. If you ask me why these objects are beautiful, I have to answer like Saint Augustine when he was asked about the problem of time: “I know what it is, but when you ask me, I don’t.” For instance, is Giotto’s Arena Chapel beautiful? Or the Neolithic rock paintings of the Chauvet Cave, or Beethoven’s 5th, or even Michelangelo’s David — are they really beautiful? Or could it be that the aura of greatness of those artworks has preceded, and unduly influenced, my love of them? Or are these questions altogether inconsequential? Can it be that here, in this exhibition, the allure of an unassuming plate, bottle, or a kettle that has given me goosebumps had more to do with the solemn presentation and the philosophical theory surrounding the Mingei movement than an instinctual reaction to an object of beauty?

Although I cannot answer these questions, I tell myself that for the time being my visual pleasure is real, and more importantly, that I should relish the opportunity to ask the questions in the first place. In the heart of Dallas there is a vivid opportunity to enjoy this kind of mystery, at least until the spring of 2024. Don’t miss it if you’re in town.

Japan, Form and Function: The Montgomery Collection is on view at the Crow Museum of Asian Art at the University of Texas at Dallas until April 14, 2024.