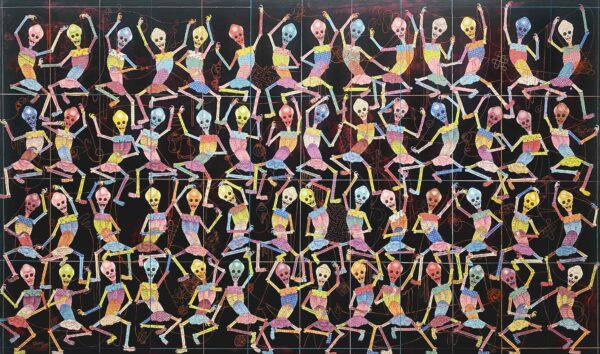

Installation view of Nomin Bold’s exhibition at Liliana Bloch Gallery in Dallas. Image: © Evan Sheldon

If humans had gone to the trouble of heeding the warnings implied by Nomin Bold’s otherworldly spirits our behavior might’ve be better, but the loss of her works’ visual impact would’ve left the world a grimmer place. As a small example of how the Mongolian artist’s goddesses and fairies could wreak havoc if they weren’t confined to her multidisciplinary works, examine the gas masks and ghouls on the walls of Lilana Bloch Gallery. Bold’s fine work is the story of what happens when a nomadic culture begins to disappear while waiting in line for modernity to strike.

Bold’s background and forte is Mongol Zurag, a regional painting style that helped preserve Mongolian cultural identity during a period of Socialism in the 20th century, and whose lineage can be traced to prehistoric cave painting. It is rooted in Buddhist pictorial tradition and characterized by bright colors and long brushstrokes. Although gods in art are usually associated with austerity, in Bold’s hands they have the vibe of satirical pranksters, or acerbic modern art critics who are in love with their own inside jokes. In a collage piece called 2020, only a grid of individual boxes remains of what was once a city. Signifiers of malls, cafes, and coffee shops sit alone on separate boxes that together form a grid, with each symbol confined to a single, isolating cube (find the brain and the Campbell’s soup can!). Gamine blue-haired spirits wear gas masks identical to the sculptural versions lining the gallery’s entry. Art, mental health, and air that can kill you — all works in this show were made in 2020, and it hits hard.

Observed up close, every single piece mixes dark themes with comforting materiality, but the star of this exhibition is Transporter, a pillowy, ten-foot-long ship of souls suspended from the ceiling. This piece demands deep study. You see the tip of the boat as soon as you enter the gallery; the size of it is startling. As the only piece floating in space, freed from gallery walls, it fools you into seeing a levitation. From a distance or in photos, it resembles a large toy boat, but most of us humans could fit easily into it as cargo. And that’s where it gets really interesting — the cargo hold looks cozy and inviting, and its skeleton crew, made of stuffed and sewed fabric, wears a collective ghoulish smile and seems to be having a great time. At once modest and rich, the material comfort of Transporter doesn’t immediately connect to death or fear of death. You want to crawl inside the cargo hold to nap, but you wouldn’t be able to close your eyes for fear of waking up in Hell. It’s one of the most extraordinary works I’ve encountered that was born of this global pandemic.

Like the happy skeletons aboard Transporter, Bold’s hand-beaded demon Rainbow Soul grimaces down at us, this time from the wall. The demon’s eyes are at the viewer’s eye level, with the fabric stuffed more densely near the top of its head, creating a forward tilt as if it could flip forward. It’s not bearing down, it’s bearing straight at, like a religious icon feigning humility among us little people. Yet it has an undeniable vibrancy, a gift for provoking mixed messages. Pointy teeth sit inside its fabric grimace, but the rest is huggable, overwhelmingly cuddly. The mouth is black and white; every other part is a rainbow, a vessel of contradiction.

Installation view of Nomin Bold’s exhibition at Liliana Bloch Gallery in Dallas. Image: © Evan Sheldon

There’s a second Transporter, a wall-hung tapestry that is cousin to the skeleton ship. Bold uses either pink, silver, or black hand-sized pillows — of the same enticingly soft fabric bewitching the ship — arranged in carefully measured rows to form a rectangle, like a screen. Though mounted on the wall, there’s nothing rigid about the piece that would prevent it from nesting on the floor or even the ceiling. The skulls are pixels; I imagined their random placement of colors might spell something with an exotic vocabulary, or that they render a graveyard, or some other remarkable thing. The shifts in color are almost hypnotic; you want to touch them, but they’re scary all the same.

Installation view of Nomin Bold’s exhibition at Liliana Bloch Gallery in Dallas. Image: © Evan Sheldon

Bold still lives and works in Mongolia, a landlocked country bordered by Russia on one side and China on the other. Her goal is lofty: integrating the comfortable attachments of the physical world to a spiritual realm that is neither Good nor Evil, but nonetheless creates influence. Balancing the emotional overstimulation of our weird global predicament and the playfulness of eternal spirits isn’t an easy harmony for a contemporary Eastern artist to achieve. Bold is taking a risk in asking her audience to welcome work that looks traditional when it is always marching forward, like the nomadic culture it honors and grieves. The effort and the ornament pay off.

Nomin Bold is on view through December 30, 2021 at Liliana Bloch Gallery in Dallas.