It’s hard to not get caught up in the chaotic turmoil of battle scenes depicted in medieval and Renaissance tapestries.

The Battle with Sagittary and the Conference at Achilles’ Tent (ca. 1470-90, Tournai, South Netherlands). Via The Met. Public domain.

The Battle with Sagittary and the Conference at Achilles’ Tent (ca. 1470-90, Tournai, South Netherlands), for example, is a fifteenth century tapestry that is so busy and full of movement that it’s hard to find a place to rest one’s eyes. A spear here, a horse there; trumpets point upward, soldiers brandish their swords, blows are exchanged, and a centaur shoots his bow with a quiver of arrows still on his back. It’s an interpretation of a scene from The Illiad, with all of the trappings of European medieval pageantry. The battle is a frenzy.

It’s scenes like this that contemporary artist Bo Joseph draws from in his current exhibition, Feeding the Beast, on view at McClain Gallery, Houston. The exhibition is comprised of two parallel bodies of work – Joseph’s well-known works on paper and his newer exploration of sculptural wall reliefs. Together, the works create a melange of history, Classical mythology, and religious iconography. In every piece, layers of meaning inspired from these other, earlier works form a 21st -century cultural stratigraphy as classic themes and stories are re-told through Joseph’s media.

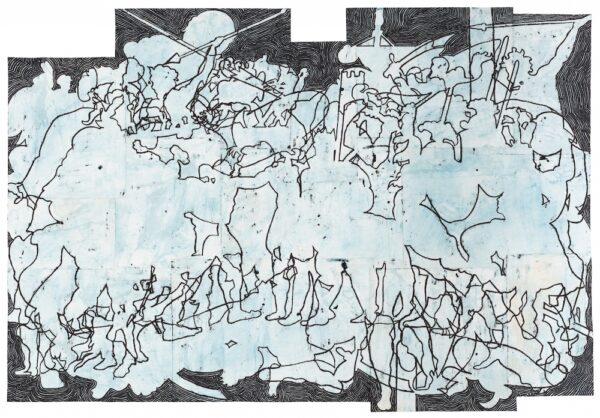

Bo Joseph, Colony Collapse, 2019. Oil pastel, acrylic and tempera on joined paper. 55 3/4 x 86 5/8 inches

Feeding the Beast is Bo Joseph’s third solo exhibition at the McClain. The name of the exhibition, Joseph explains on an artist’s Zoom talk hosted by the gallery, carries a double meaning. On a personal level, it refers to nourishing his own artistic passion; on a larger scale, it connotes how society pursues its insatiable obsession with profit and progress.

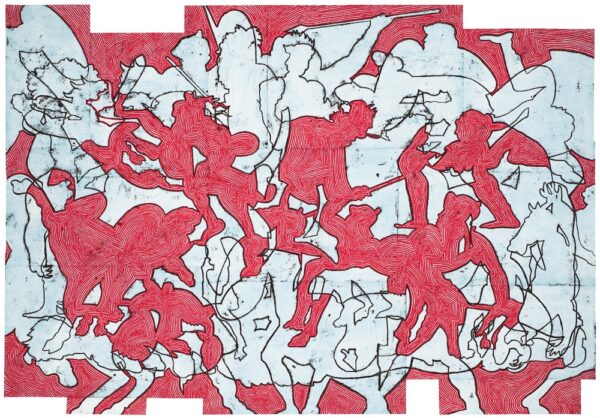

Bo Joseph, Beneficiaries of Destruction, 2020. Oil pastel, acrylic and tempera on joined paper. 55 3/8 x 80 1/4 inches

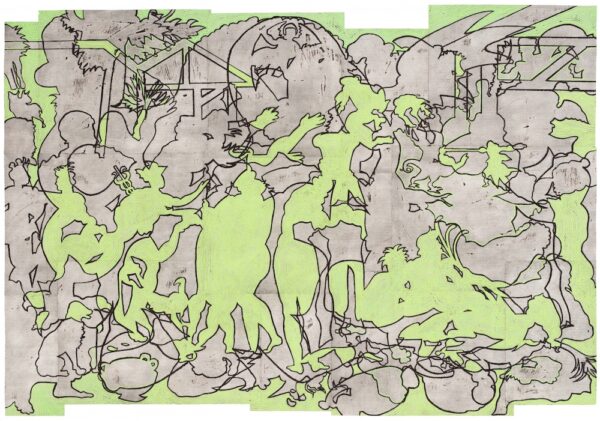

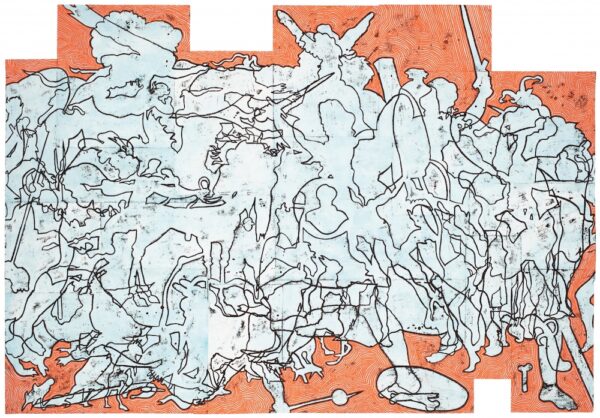

The large-scale works on paper most closely resemble the medieval and Renaissance tapestries that inspired them, in both size and in the frantic tension of conflict that they capture. These pieces, made in 2019 and 2020, are all oil pastel, acrylic, and tempera on joined paper. The figures, buildings, and objects in each of Joseph’s scenes are outlined in black, and the “empty” space in and around the figures is filled in with monochromatic radiating lines. It is as though Joseph outlined the figures in The Battle with Sagittary and the Conference at Achilles’ Tent, added in classical and iconic symbols, and then re-animated the wild battle scene with the motion of the colored lines. The colored space frames the figures in some of the works; in others, color fills interior spaces, emphasizing the silhouetted scenes.

Bo Joseph, Chasing Ghosts, 2019. Oil pastel, acrylic and tempera on joined paper. 55 3/4 x 80 3/8 inches

“The means of war have changed, but the rules have stayed the same… . Battle leads to the ideological catharsis that comes with war,” the gallery’s website quotes Joseph. In the artist’s discussion, Joseph mentioned that the pieces do not refer to a specific historical tapestry or scene; rather, they’re inspired by the genre. Look at each piece long enough, though, and familiar elements stand out — a medieval-esque trumpet in Feeding the Beast, the Rod of Asclepius in Chasing Ghosts, weapons like swords and spears held aloft in Colony Collapse. The tension between the silhouetted figures and the space around them is palpable.

Bo Joseph, Catching Ghosts: Anima/Animus, 2020. Casein and acrylic on resin, fiberglass and foam. 60 x 37 1/2 x 1 1/2 inches

The wall reliefs sculptures in the exhibition are portmanteaus of various global mythos and cosmologies. These works, all from 2020, are casein and acrylic on resin, fiberglass, and foam. As symbolic composites, it’s easy to find the non-Western inspirations and iconography that underscores Joseph’s work, like West African masks or Persian mythical creatures. Simorgh, for example, takes its inspiration from Farid ud-Din Attar’s 12th-century poem A Conference of the Birds. Joseph’s interpretation of the poem and simorgh legend vertically juxtaposes four different birds from four different cultural traditions.

Bo Joseph, Catching Ghosts: Shadow Aspects, 2020. Casein and acrylic on resin, fiberglass and foam. 48 x 33 1/8 x 1 1/2 inches

One of the themes that underscores the exhibition is appropriation, reinterpretation, and how stories are told and retold over time. The Battle with Sagittary and the Conference at Achilles’ Tent, for example, is the ancient Greek myth told through the experiences of 15th-century artists; shadows of those same stories appear in Joseph’s work more than five and a half centuries later. These oft-told stories form tropes (like The Illiad, or the myth of the simorgh) that in turn become cultural palimpsests — social texts where each telling is superimposed on its previous iteration.

Bo Joseph, Catching Ghosts: Shadow Aspects, 2020. Casein and acrylic on resin, fiberglass and foam. 48 x 33 1/8 x 1 1/2 inches

In Feeding the Beast, Joseph’s nuanced retellings show up in bits and pieces as allusions and fragments. The works are full of shadows of a bigger, older, global set of stories.

On view at McClain Gallery in Houston through Dec. 30, 2020.