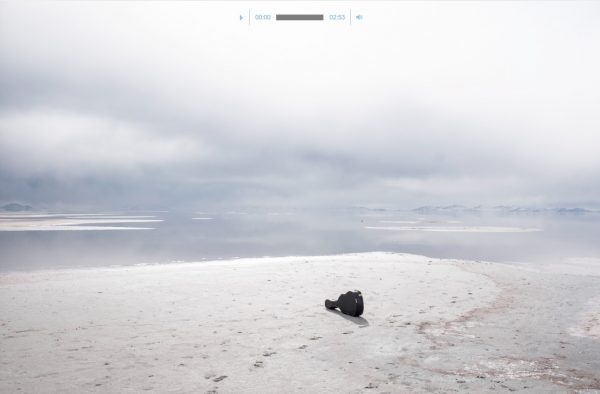

Porch Swing Orchestra is a project by Austin-based artist Barry Stone. Simply put, it is a webpage with one image and an embedded audio track play button. Another crucial component is an email from Stone when the next installment is up. The single website images are typical of Stone’s pictures — landscapes, sometimes with a figure — that are often modified by way of manipulating the digital image’s file code. You can hear a short audio clip of (most likely) Stone playing guitar, and the atmosphere of his surroundings. It sounds something like an accidental field recording, or something you’d find in your Voice Memo recordings. It’s not amateurish or casual — it has the feel of a personal experience, a recording you would make for yourself and not something to be shared for “likes.” Stone’s project is rooted in a critique of the production of “likes” as part of the larger commodification of digital content — both personal and as fine art. Although I’ve known of Stone’s Porch Swing Orchestra project for years now, it was clear to me a couple of months ago that my reaction to, or relationship with, this work has changed. I talked to Stone on June 5th.

Chad Dawkins: I know Porch Swing Orchestra because I get an email from you every week with a brief description and a link to the project website to see that week’s installment. When did it start and how does it work?

Barry Stone: It started Spring 2018, and what you said is pretty much how it works. I began by sending an email to people in my contacts asking them if they wanted to see my new project.

I make a recording, usually on my porch, playing guitar, and it includes the sounds of any birds, cars, or people around. I combine this with a picture taken onsite, usually of the yard or something I am immediately drawn to. It has been intentionally domestic, but if I travel, it has travelled with me. I made one from Spiral Jetty, and Del Rio, and some in Maine. But the vast majority of them are made on my porch — literally on my porch swing.

CD: But every week, if you visit the website, there is only one entry — the one made for that week. Explain that presentation.

BS: Yes, each new entry displaces the last. There is no archive, and there is no way that you could listen to previous iterations again. The link I send in email directs to the homepage that changes every time. It’s confusing if you click on an old email and see that the description doesn’t match what is currently up.

CD: It interests me that it is almost anti-archival; it doesn’t add to the feed. Given that you could theoretically scroll through Instagram all the way back to its beginning… .

BS: Exactly, one of the reasons why I wanted to do it on a website instead of through something like Instagram is [social media platforms’] inherent constraints. On Instagram, with all the information being put out, there are no links — except for the one available in your bio. Of course it would be possible to make linkable posts, like in the comments, but they don’t want that — they want to keep you on the platform, in that scroll. So it was partially out of frustration with that, and the fact that, at the time, you could only post videos up to one minute long, that I did it this way. Porch Swing audio is usually only a minute too long, so when I started I could only post a snippet.

I also wanted to make something online that is free and interesting to look at that doesn’t try to sell you something, or doesn’t mine your data in return. The internet has, of course, lost most of its utopian promise and has largely become the dystopian black mirror that we’d hoped it wouldn’t, but I still think that there is a lot of potential there and a lot of amazing content that is also so ephemeral.

CD: This project is designed to change weekly, so it is exponentially slower than the content change on IG, but that pace is still relatively timely, and must present a challenge to keep up with.

BS: Yes, it is. But that’s why it is come-and-go. You can come by and see the site, but it’s not pushed like a constant. I also don’t want to make you feel guilty about catching up through a pile-up of emails like so many unread New Yorkers on the nightstand, or the newsletters we get with actionable items that we all miss out on, and all of that. For me, I wanted to do it weekly just because it gives me a schedule to keep for making, which is something I really needed. I was looking for something new, or was losing interest in traditional exhibitions, and I wanted some form of practice that could sustain itself, but that needed some kind of an outlet — some kind of communication, because I think that is a big part of what exhibition is. Early on, in the early 2000s, before Flickr and these things, I had a weekly picture that I did and put on my website. Just like this, I sent out the picture with a little description about where it was taken, and this started building into something like a slow-motion movie of sorts. I did that for a number of years, and then when Flickr came out I felt kind of dumb. Here I was with my “picture of the week” like an old man carting something around in his wheelbarrow. It seemed ancient to send an email when Facebook and everything started up and everyone could share so easily. But now, in the face of billions of pictures being uploaded every week, with Porch Swing Orchestra, I send that email out and people will write back. We will have an actual conversation because of it — more than a “like”.

CD: How do you think of the Porch Swing Orchestra project in form? Do you think of it as an artwork, as an exhibition, or something auxiliary to your practice?

BS: It feels like it is its own thing. It’s art because there are pictures involved, I guess. Really, before I got into art, I played music. I toured and played a lot in the 1990s, so that was sort of my first life in creativity. When I starting doing visual art and went to grad school for it, I always wanted to get music back into it, but it never fit right. It always felt forced — that I was writing a soundtrack to something else. I just couldn’t get those worlds to come back together. Certainly artists use music, like a lot of Christian Marclay’s work, but that wasn’t what I had in mind for my work.

So I found this as a way to explore that. I don’t have space or time to really pursue music anymore, but I found that this was something that I could just do. I have tons of recordings of my musical material and I love field recordings. I thought “that’s it,” it just goes together as a way to capture an ephemeral moment, a chance recording, and makes it possible to present that in a way that makes sense to me. It stays simple and enjoyable, and this has become important to me — thinking about things in a material way and about gifts. That’s what I am trying to aim for — something that resembles a gift in the way that Lewis Hyde describes when he talks about gifts. It’s not something I make in hopes of any kind of return.

CD: Knowing you started the project over two years ago, it makes me think about the project in light of its existence before, and now within, the pandemic. There has been a move to emphasize collaboration in recent years which seems to have really accelerated recently. It seems that you’ve started collaborating on this project recently. Collaboration involves a certain level of risk — right now the risk of contact — but more so the risk of losing control and opening up a situation to chance. Do you feel like your collaborations on this project have anything to do with self-isolation or being stuck at home? And do you see that faith in risk related to these ideas?

BS: In the beginning this project came to me out of nowhere — like while I was folding socks. There wasn’t any plan for it and I didn’t think about it too hard. Same with the collaboration; I just thought I would reach out to somebody and we could both play from our porches. I’m sure I absorbed something from watching videos and seeing how others were collaborating during the pandemic, for sure, but I realized what I was already doing was just made for it. Of course, you also get tired of hearing yourself, seeing your own pictures, listening to your own ramblings on a fretboard, so I made a list of people I thought might be up for playing along. Then I asked others if they knew of other people that would be interested, and people were really responsive.

It has been really surprising to see what people can do and what they will send you. I have been completely surprised and challenged by it. The latest have been with Tamara Gonzalez, an artist in upstate NY, who sent me a song she sings in Portuguese. I love it. I worked to play guitar over it and it took me a long time to figure out what to do, how to add to it, but it was fun figuring it out. I’ve also collaborated with Rainey Knudson humming — she’s been so responsive, and I hope we can do another one together. I did one with Katy Chrisler, a poet and writer based in Austin, who wrote an incredible poem for the times — the music was recorded in a storm with thunder in the background. It’s epic, really. Bob Warner, who I used to play with in New York — he’s an amazing guitarist who can play anything. Emily Scarlet Kramer, a writer based in LA — she’s recited a poem and plays violin.

CD: Do you feel like your work overall, or your working method, has changed since we were mandated to stay at home?

BS: I feel like things have certainly changed. Of course it’s hard to tell, if the ground is still shifting all the time. I’ve kind of worked the same way for a long time in terms of taking pictures around where I live and who I live with — so my family has always shown up. Sometimes the best pictures are the ones that happen when I go with them someplace, if the place is more interesting. So in some ways things haven’t really shifted for me; maybe the thinking has come around that it is more interesting to look at your neighborhood again, or what have you, but I’m sure this general thinking won’t last long. So I feel like those kinds of things have to do with me doing what I have been doing, and the rest of the world, so to speak, has changed. Maybe this mode of working is more suited to our current situation. I feel like I am working more than ever; I’ve been lucky to be really busy.

CD: Do you feel like your subject matter is changing?

BS: It’s interesting to think about that; I may have a myopic perception of my own work. But I’ve always made pictures of family and things around me, so to me, that is a constant. But I’ve always wrestled with it, wondering if it’s “too diaristic” or “too saccharine” or just boring. But I know early on in shows I would want to include photos that were more conceptually-based or formal. I think that in many ways that approach is safer because you can hide behind some sort of material investigation or some theoretical argument. You know it’s going to be smart and look good, so you don’t have to worry, to get defensive. But then here is something personal and that is different.

CD: But can’t we say the same of the opposite? Let’s say there is a picture of your family — does that in some way present itself in the same way? We can critique it formally, but is it fair to critique it terms of the subject matter?

BS: So I can win in both approaches! Yes, I see. I think if we critique the subject, or content, of the more conceptual work, then I don’t get personally injured. And I think you can critique the subject matter of these pictures, for sure, but the relationship is different. Sometimes these become issues of etiquette, too. And we must recognize the position of privilege that contemplating a shift in our subject matter represents.

The boundaries of art, life, and politics — which are fuzzy in the best of times — become indistinguishable in a time of crisis. We as artists need to look at what we are doing and assess it. We need to ask of our own work: “Is this saying what I need to say or doing what I need to do in the world?” Artwork needs to come from an authentic voice. If it’s not, or if you pivot to some subject or idea that isn’t fully formed, then the chance of it falling short, of even your own expectations, is high. But that is why art is interesting, because we are always failing to a certain degree — those objects we make can never quite meet the experience we are trying to articulate. We can’t solve art, and never will, because we haven’t solved experience and perception.

Porch Swing Orchestra’s website is here, and its Instagram is here. To join Porch Swing Orchestra’s mailing list, email [email protected].

1 comment

I love how contemporary artists explorer experience and existentialism. I just wonder if it’s still in the same vein of the Postmodern mode of “self-awareness”.