Absolute Texan Larry McMurtry’s 1999 pseudo-memoir Walter Benjamin at the Dairy Queen: Reflections at Sixty and Beyond is a compact and wonderful book that ruminates on, among a plethora of other topics, the complex state of storytelling and its relationship to Texan spaciousness. At one point, McMurtry makes the (subtextually self-deprecating) argument that the American West “has not, as yet, yielded a great book.” He goes on to argue that this might be photography’s fault, as European colonization of the Western United States moved more or less in lockstep with the development of the camera:

Writers weren’t needed, in quite the same way, once the camera came. They didn’t need to explain and describe the West to Easterners because the Easterners could, very soon, look at those pictures and see it for themselves. And what they saw was a West with the inconveniences — the dust, the heat, the distances — removed.

As straightforward as they might appear to be, early photographs of Western landscapes are now understood to harbor a great deal of myth. Rephotographic surveys by Mark Klett and others have shed light on just how much a fundamental aspect of the medium — the frame — might manipulate viewers’ impressions of these scenes. But the photographic literature of the North American West chugs on, ever complicating itself in reference to, or subversion of, its own colonial past. McMurtry’s comment that “anyone who spends much time with the photography of the American West will receive a vivid lesson in how quickly world succeeded world” still rings true when looking at newer generations of work.

Now, to my mind, contemporary Texas photographers (I might consider myself one of these) continue to embrace vastness because it’s still really like that out there. McMurtry refers to the “relief” and “exhilaration” of the “Western sky, with Western horizons beneath it.” A former North Texas ranch child, he claims he didn’t notice the crowdedness of cities when he went to college at Rice University because he was overcome by the availability of books. A desire for space, “sky deprivation,” didn’t hit him until he moved to Virginia. But I don’t think he is giving Houston enough credit. It is likely that I exude a little bit of longing here, seeing as I am writing this some 1,700 miles removed from those horizons, but I’ve found that the sensation of space has a powerful presence even within Texan cities. It’s a weird quirk of the landscape that, once experienced, may be impossible for a photographer to shed. We might have little choice but to seek it out wherever we go.

Right now, for instance, I’m at a Whole Foods in Gowanus. Brooklyn. I like to come here and write. They have a great parking lot and nobody bothers you. You can really spread out. Anyhow, here’s a little of what’s been going on back in Texas:

Field Work by Jason Reed. Published by Victory In the Wilderness Museum, 2022. Find the book here.

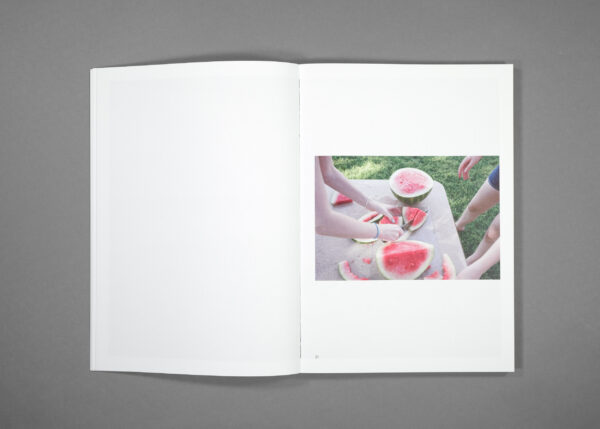

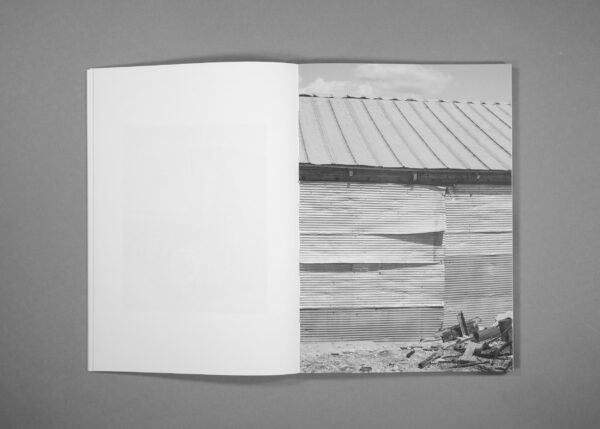

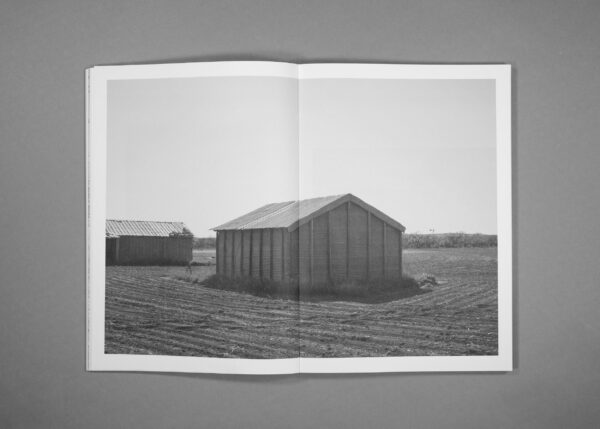

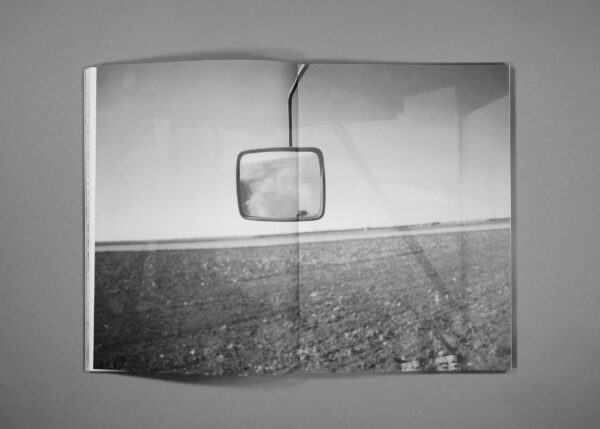

Like McMurtry’s folks, Jason Reed’s family has been in the Texas plains for generations. Field Work charts the slow, steady advance of work over twenty years on his wife’s family’s farm outside a town called Wall. The book paces along through eighty-odd photos with the sturdy efficiency of the cotton farm it depicts, but the labors are punctuated by consistent glimpses of genuine intimacy. Young girls are seen in one frame eating watermelon, then later being taught to drive a massive machine which I cannot name because I am from a city. It can be assumed the girls are Reed’s daughters. But the adults, and even the tractors, the fields, the barns, they are family too.

In the photographs, everything is treated with the same level of loving, albeit slightly removed, attention. Perhaps the bit of distance in the pictures comes from the fact that Reed married into the endeavor, or maybe it is just the nature of the photographer to let things be as they are. Either way, twenty years on he still seems fascinated by what’s happening out there.

Some of the pictures, which depict massive blocks of raw cotton isolated in a potentially endless expanse, recall earlier generations of “Western” “landscape photography.” Specifically there is Lewis Baltz, whose intentionally anonymous photographs of California industrial parks are formally similar to Reed’s cotton work. There are even tonal similarities in the monochromes — flatness is favored over visual drama. But where Baltz’s pictures emphasize sterility to a cynical degree, Reed is able to instill his minimalist frames with the exact opposite attitude. Here there is specificity, familiarity, and care. Turns out, the incremental progress of agriculture produces plenty of notable views.

At the back of the book is an index of photographs that is not organized by page number. Instead, Reed has arranged the thumbnails according to when the photos were shot, with detailed, metadata-like timestamps for many of the frames. This reveals the sequence in the book to be entirely shuffled, which is not apparent at first glance, and actually counterintuitive. Photography messes with time, it’s cool: I’m actually thumbing through a harvest of harvests, fragments pieced together over decades into one complete picture of rural consistency.

****

Beautiful, Still by Colby Deal. Published by MACK, 2022. Find the book here.

Colby Deal’s immense record of Houston’s Third Ward is a long visual poem. It will hopefully be taken up by educators looking for updated examples of how photography in its most straightforward form, despite all its quirks and inefficiencies, can articulate ideas that go far beyond language.

The Third Ward is a historically, predominantly, Black neighborhood near Houston’s core. Like so many similar places around the country, it is imminently threatened by gentrification. But Deal turns his camera away from invasive development and dedicates time to more deeply rooted people and locales. Figures drift loosely and without hierarchy between formal portraiture and something much more like a snapshot, though to label any of the pictures as belonging to a “type” would be reductive. The core strength of Beautiful, Still is its ability to define photographic terms for itself in a way that feels at once fluid, open, and complete. These generous terms help Deal express sincere affection for his subject.

Some of the photographs drift gently out of focus. These pictures may or may not result from technical mistakes, but their presence in the edit is quite intentional. The same goes for underexposures and other misfires. Deal seems to possess a philosophy that pictures succeed not on the “correctness” of their technique, but on what resonates from the frame.

Some of the blurrier pictures have the feeling of half-remembered moments among moments, like scenes observed from a speeding car. One of these shows a large print of Deal’s own picture from earlier in the book, wheat-pasted onto the side of the building. It’s a wild and commendable move; a dreamlike recollection of an excellent portrait that sneaks into the sequence and muddles the reader’s understanding of authorship and time. It also declares Deal’s lasting presence within the community he photographs.

That photo may encourage a reader to flip back to the initial appearance of the portrait, to double check their memory. If they do, they are liable to reencounter, in another picture, handwritten signs affixed to a fence post that say, “THIS IS GRANDMA’S HOUSE. WHERE AS A KID I PLAYED VIDEO GAMES AND RAN AROUND OUTSIDE WHILE/AT THE SAME TIME I WATCHED JUNKIES AND PROSTITUTES WALK AROUND.” With the wheatpaste in mind, one may be left questioning whether this is an autobiographical statement.

It’s true that there is a sense of precarity in this book. There are boarded up buildings, and one that burns; a fence that is missing its fence bits becomes a picture frame for a distant ruined sofa. This is a working-class Black neighborhood, a stark contrast to the sleek half-billion dollar cultural institutions I’ve visited three miles to the west. But the precarity is undermined by a consistent radiance of communal strength. Deal relays, with his pictures, a complex web of human interaction that is not exclusively cheery, but continually marked by moments of joy. Children inflate balloons twice the size of their heads and goof around on porches. A classic, posed, “group photo” near the center of the book is an outlier that helps solidify the bond between the photographer and his collaborators in the rest of the pictures. Then there are the three men smoking cigars in their white tuxedo jackets outside a strip mall, their faces slightly obscured by the limitations of the medium—it’s photography! It’s really doing a photography!

****

Lost Pines by Barry Stone. Published by Sunset Commission. Find the book here.

This book is haunted.

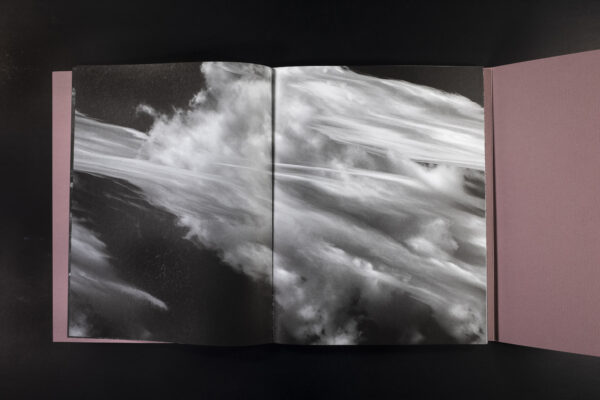

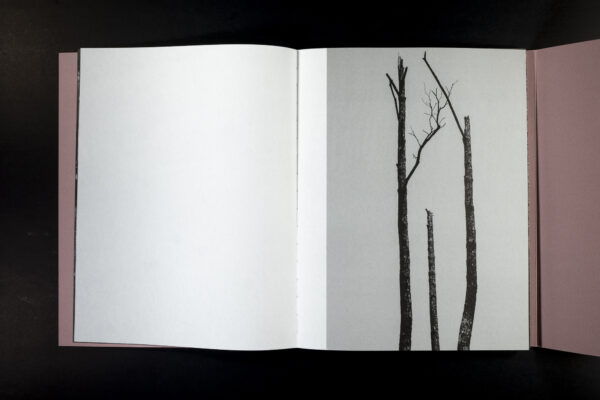

Barry Stone decided to photograph the aftermath of the 2011 wildfire in Bastrop, Texas, which engulfed 32,000 acres of forest, destroyed more than 1,600 homes, and killed two people. These photographs form the main text of Lost Pines. They are dark, monochromatic, and slightly surreal pictures that depict a natural world returning from ruin. Charred remains of old trees are intertwined with new growth. There is some optimism in this budding rebirth, but hope is quickly disrupted by a barrage of unshakable, post-traumatic thoughts. It gets personal: Stone’s tripod mimics a burt tree in one of the pictures. There is even something wrong with the sky; the clouds seem broken. The artist, who has a record of making conscious digital tweaks to his pictures, is up to something here.

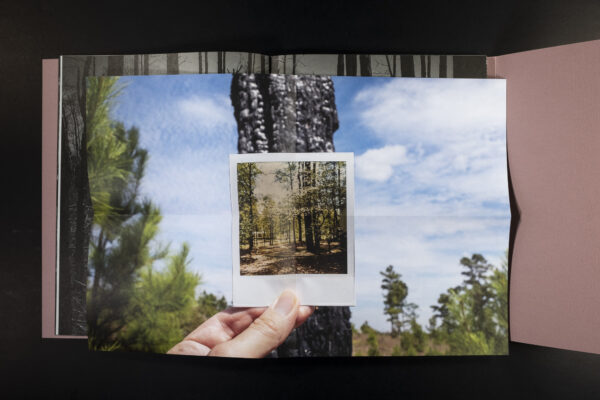

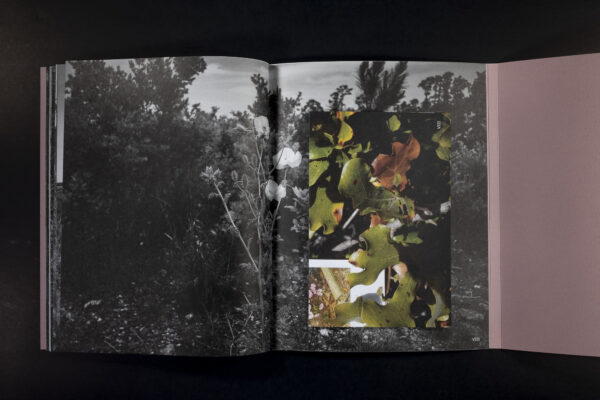

There are nine unmissable color inserts shuffled into the black-and-white pages. Eight of these are fold-out photographs that suggest a much more personal tragedy. Stone carried a stack of Polaroids depicting cats, gardens, and elderly people out into the burned woods. He photographed these photographs out there — old memories like new shoots from the ash. The physical act of removing, unfolding, and experiencing these small posters is disturbing. It reminded me of when my grandmother died and every drawer in her house had to be examined bit by bit. The final insert is a small zine. This one makes Stone’s motives, and his state of mind, as explicit as they’re going to get.

Lost Pines is a surprisingly somber meditation on some variants of loss, on how one tragedy can recall another. It is a book that wants readers to physically dig. As layers are peeled back, ghosts are revealed. I am curious if Stone wound up here by accident, through digging of his own. The most difficult memories don’t just go away.

2 comments

The McMurtry book sounds fascinating. Ordered! Thanks for the tip!

Always nice to read other’s musings on photo books. I really enjoyed digging into my copy of Lost Pines, now I need to seek out the others. Thanks Bucky!