Barry Stone “Stand Scape, 9064,” 2022, archival inkjet print, 34 x 51 inches (paper).

In 2011, a massive wildfire in Bastrop County, Texas — the largest in state history — all but destroyed the area’s Lost Pines Forest. Photographer Barry Stone began documenting its profound aftermath the following year, poignantly capturing the environmental destruction and its slow regeneration. Stone’s photos are now on view in an exhibition at Lora Reynolds Gallery in Austin, along with a special edition book, both titled Lost Pines.

Known as a “disjunct population,” the Lost Pines earned their poetic name through geologic estrangement, cut off from the rest of the loblolly pines 100 miles to the east, at the end of the Ice Age. Stone, who now lives in Austin, grew up in East Texas, where those other pines towered over his childhood. Lost Pines tells a story about places in time that are separate but connected — and about not one fire but two.

Barry Stone, “Cloud Smear 9093_3_1,” 2022, archival inkjet print, 34 x 51 inches (paper).

“There had been an accident,” Stone writes in the book’s epilogue. “On September 12, 2002, my granddad died alone in a fire that engulfed his trailer.”

In both the exhibition and its companion piece, Stone tenderly sifts through these two events, nearly 10 years apart, and now 10 years on. Part photo album and part art book, the 80-page volume consists of black-and-white images that transform a desiccated landscape into a formalist revelation. A white smear of cloud moves like smoke in one image; a single dark pine rises up to the sky in another. In every photo, a sense of something still to come. Tucked in these pages are neatly folded color posters, capturing new (and old) life amongst the scorched remains. Polaroids that were taken by Stone’s grandparents in Magnolia, Texas years ago appear in some of these color inserts; pictures of their old property placed on patches of regrowth as a way to collage different lifetimes into a single moment.

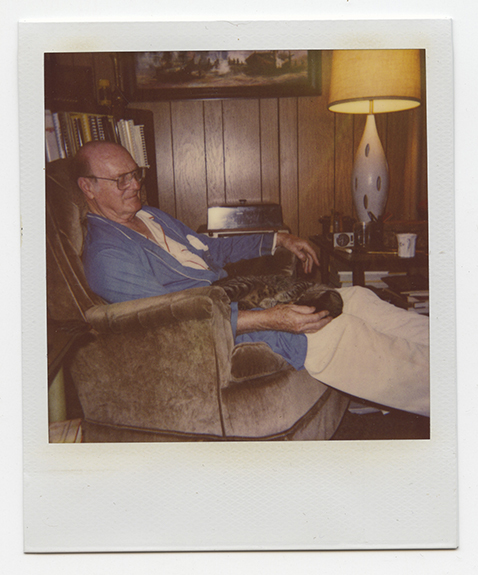

Original Polaroid (Fred in Recliner with Cat), Magnolia, Texas, taken by Jean Stone, year unknown. 3-1/2 x 4-1/4 inches.

Other inserts reveal haunting scenes of the photographer’s grandfather’s home after the fire that claimed his life. These images are a wrenching glimpse into someone else’s tragedy: melted glass that hangs like taffy, a king-size bed covered in soot, empty frames on a burned-out wall that Stone has solemnly titled Black Canvas. An undated Polaroid of his granddad Fred, taken by his wife Jean, shows him sitting in his recliner with a pet cat, happy and content. It is a difficult before-and-after account, but what begins to come through, like a tree sprouting up from the forest floor, is this prevailing sense of motion and life — that it goes on.

A few years ago, Stone was emptying out a drawer when he found an undeveloped roll of film; photos, it turns out, of his children’s births as well as his grandfather’s trailer after the accident. “I didn’t remember taking the pictures and it was shocking, honestly,” he recalled at the show’s opening in early September. “So the pictures sort of complement each other, they are bound by trees, nature’s cycles, and just coming back.”

Installation view of “Lost Pines” at Lora Reynolds Gallery, 2022. Photo by Colin Doyle.

Stone was living in New York at the time of the Magnolia fire, but returned to Texas to help salvage what he could, including his grandparents’ old Polaroids. These tiny pictures stand out from the enlarged black and whites on the walls, as if peering through the keyhole of Fred and Jean’s own eyes. A pink-blossomed Polaroid, framed just above Stone’s book — and flanked by two large images of a mending Bastrop — quietly centers the story being told. Directly across the way, the only two photos from the trailer fire on view in the exhibition hang on a carbon black wall.

Stone, who is also a musician, says the book reads a bit like a score, with a sequence and tempo that moves faster in some parts and slower in others. Even the works on the gallery’s walls possess a sort of musical syntax. Using a “data bending” technique for certain digital shots, Stone intentionally, arbitrarily scrambles the image file code so that the picture begins to “talk back.” So that, as he puts it, everything comes from itself. Bent Forest is a good example of this data bending, the way its dead trees uniformly wobble in an altered state. But then another photo from that same burnt forest seems to bend without any provocation — a testament, says Stone, to the intense effects of fire and heat.

Barry Stone, “Bent Forest, 9264_1,” 2022. archival inkjet print, 51 x 34 inches (paper).

According to the Texas Parks and Wildlife website, it will take a generation or more for the Lost Pines Forest to recover, but it is slowly coming back. Lost Pines speaks to the catastrophic beauty and unpredictability of nature; to the ceaseless cycles of life, loss, and renewal. And to the photographer’s own memories. Stone grew up in Spring, Texas, not far from his grandparents’ place in Magnolia, where those loblolly pines were fully in their element. A connection that perhaps led him to the Lost Pines, and a reminder that nothing is ever fully cut off from the rest. Everything comes from itself.

Lost Pines is on view through December 3, 2022 at Lora Reynolds Gallery in Austin.