I first met Michael Galbreth sometime in 2013. I was fresh on the scene, but somehow (I honestly couldn’t tell you how; probably simply because I lived in Houston), I was hip to The Art Guys’ work. It struck me in a way that other art hadn’t yet, because it was so funny. Surprisingly and gut-bustingly funny.

I never knew art could be funny. Growing up, I was only familiar with art in the history books — Rubens, Monet, Dürer — and it was art that struck a blow, carried weight, and may, only occasionally, have a sly bit of wit peeking through. The Art Guys were different. They combined a deadpan delivery with conceptual and absurdist underpinnings, and so theirs was the first artwork that ever made me laugh out loud. I found solace in this, not only because I was beginning to realize I was an absurdist at heart, but also because it presented an inroad to other kinds of art. And even if I didn’t understand every nuance of an Art Guys piece, I got the joke. And the joke was good.

I know many others felt that way and continue to feel this way about The Art Guys and their work. A current of incisive humor ran through everything they did, even if the humor wasn’t foregrounded. One of my most memorable Art Guys experiences was their 2013 performance Never Not Funny, for which they each took turns telling “a guy walks into a bar” jokes for eight hours straight. As expected, the performance devolved into rambling nonsense, with Michael wearing a lampshade on his head. To this day, it is one of the most memorable and surreal artworks I have ever encountered. It wasn’t just humor in art. It was comedy in art.

I think a lot of artists shy away from humor and comedy for a couple of reasons. First, there’s a perception that if something is funny it can’t be serious (while gravity and humor are, in fact, natural partners); and second is that successful comedy, like successful art, requires a wholly unique view of the world. So to couple comedy and art together in a way that really works requires a very special type of person.

Cue Michael.

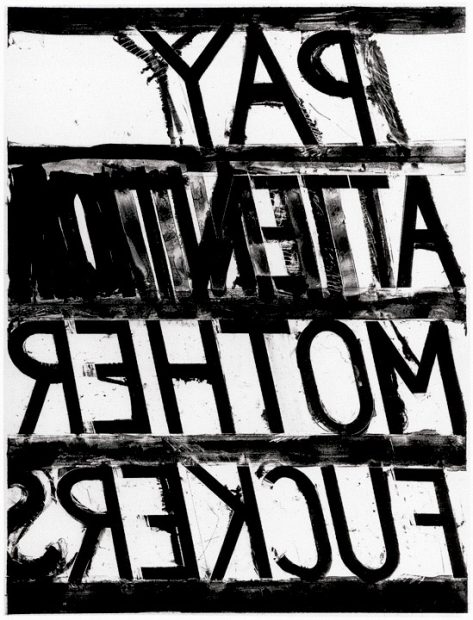

The reason Michael was such a remarkable artist (and beloved by a great many people in Texas and beyond), is because he had a way of looking at his surroundings with truly open eyes. He wasn’t simply observant or discriminating — though he was those things. But there’s a simpler way to describe how his mind worked: He paid attention. And if you ever heard him speak or conversed with him, he urged you to pay attention, too.

‘Nap,’ an image from Michael Galbreth’s Instagram. Source: @michaelgalbreth

There’s a lot you can learn about the world and yourself by simply observing (really focusing on) what you surround yourself with. I took a course Michael taught at the University of Houston in 2015; on the first day of class he lead us on a loose tour around campus, asking us if we knew the difference between whisky and bourbon; he held up the leaves of red and white oak trees to note their differences, and pointed out the oppressive beauty of the brutalist buildings that the students walked into every day but never thought to consider.

In the same course (and in future courses too) Michael began every class with an image of Bruce Nauman’s 1973 lithograph Pay Attention, which (not so politely) emphasizes what seemed to be Michael’s life’s motto. (Michael would occasionally also note that he wasn’t much of a teacher — a claim that was undermined anytime he opened his mouth, as he was always imparting wisdom, solicited or otherwise.)

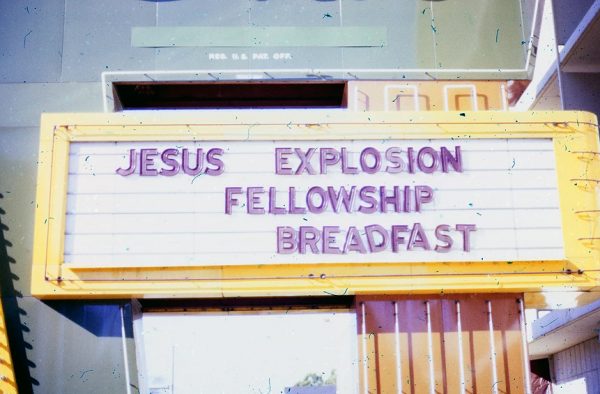

The concept of paying attention extended to every aspect of Michael’s life. He was an incessant driver of places, and would often just get in his truck and cruise the city for hours, looking for something, anything under-observed. Because of this, he (I think) knew Houston’s backstreets and roadside gems better than any of us.

‘Relativity,’ the last image from Michael Galbreth’s Instagram. Source: @michaelgalbreth

This hyper-awareness extended to his travels outside of Houston. When I was green, before I went to New York for the first time, I asked Michael for recommendations, thinking he would suggest an oddball activity that wasn’t on my list. Instead, he told me to just walk around, look, and listen — don’t take a cab, and God forbid don’t go underground and take the subway. Instead, he said, walk around the city with your eyes and ears open. (His other recommendation was to get a drink at Grand Central Station, because if you’re sipping a cocktail you have an excuse for an extended spying session over the vast hall of people coming and going.)

A photograph by Michael Galbreth, 1978-1980.

Importantly, Michael was a payer of attention to everything — nothing was too low or banal to pique his curiosity. Most of us keep our sights on the things we’re told are important — the news, politics, popular culture, sports — and these only change as our own interests shift. While Michael had a few blindspots, he paid attention to the kinds of details many of us block out: pipe storage yards, the patterns of hat displays in a truck stop, garbage and hidden things — countless situations up for an absurdist interpretation, but only if you’re paying attention.

An image from Michael Galbreth’s Instagram. Source: @michaelgalbreth

I feel that to fully pay attention is to appreciate life. I owe to Michael a lion’s share of this enhanced model for living; through his art and life, Michael encouraged me to revel in the contradictions, the humor, and the blunders that I encounter daily. And I know I’m not alone in learning this from Michael. Many of us, consciously or not, picked up this way of going about life from him, which is why his death sent shockwaves throughout our community.

What we can do now, collectively, to remember and honor him, is to pay attention. And laugh. It’s what he’d have done.

5 comments

Wonderful description of Michael and suggestion for us all.

Very perceptive observations and descriptions of Michaels gift to the world, not just art. Love the way you acknowledge him as a lifelong educator.

Brandon: Great piece of writing and a wonderful tribute.

Perfect. Not perfect. Perfect!

Art Guys seemed to be the only people there, in a city and environment where there should have been more. Art Beacons…