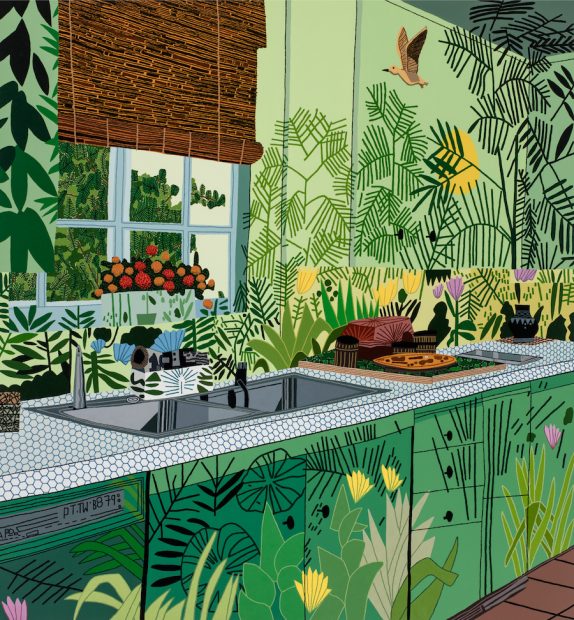

Jonas Wood, Jungle Kitchen, 2017, oil and acrylic on canvas, 100 x 93 in., The Broad Art Foundation, courtesy the artist and David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles, photographer credit: Brian Forrest

Jonas Wood makes big, cheery, funky pictures that wear their love of the historical avant-garde of more than a century ago on their sleeve. Nevertheless, their aesthetic may owe as much to a childhood spent enraptured by Hanna-Barbera as it does to an adulthood in awe of Matisse and Picasso. In other words, the 42-year-old Wood paints like a lot of other artists right now — artists in his hometown of L.A., in New York, and presumably elsewhere. While these artists do not form a group or a movement, their work does cohere visually, identifiably of the present moment — a period style, if you will.

Like several of his peers, Wood has met with great success. Collectors snap up his work at auction for prices in the low seven figures. Consequently, museums have had to pay attention. Thus the Dallas Museum of Art’s current mid-career survey of some 33 works spanning 13 years.

The exhibition centers on an impressively vast gallery hung with suitably sizeable landscapes and domestic interiors — Intimism writ large. The interiors’ thriving houseplants compete with the landscapes’ lush gardens to suggest the indoor-outdoor porousness of comfortable middle-class lifestyles in clement seasons or parts of the world, such as Southern California. In Jungle Kitchen (2017), the exterior has surreally invaded the interior; both flowers on a windowsill and the foliage seen through a window pale in comparison to the preternaturally vibrant flora and fauna on wallpaper and cabinet doors. The comforts depicted extend to luxuries in the wood-paneled room filled with books and art in Ovitz’s Library (2013), ostensibly documenting the house of the Hollywood agent (and major collector), Michael Ovitz.

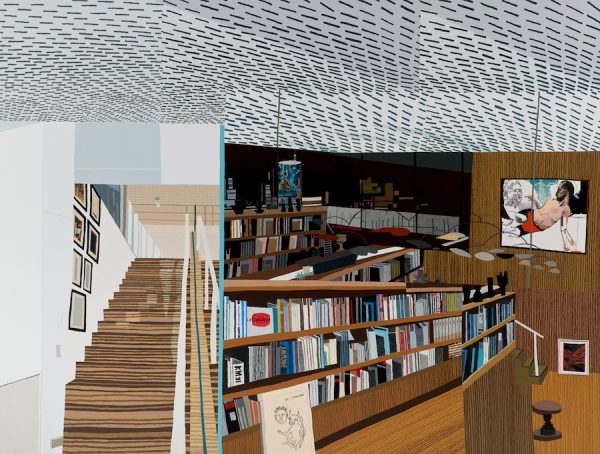

Jonas Wood, Ovitz’s Library, 2013, oil and acrylic on canvas, 100 x 132 in., Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Gift, Anton Kern Gallery, New York, and the artist, 2013, 2013.55, courtesy the artist and Anton Kern Gallery, New York, photographer credit: Brian Forrest

Rendered in blocky areas of flat color, the image also includes anomalous spatial dichotomies — a nod to Cubism, no doubt — and possibly to some notion of a critical-theory-driven problematizing of naturalistic and holistic representation. But instead of Cubism’s fracturing and reassembling of the world into a new pictorial whole of complex kaleidoscopic facets, Wood gives us a simpler, more straightforward cutting and pasting. In Ovitz’s Library, he vertically crops a staircase hung with pictures and abuts it against the room with bookshelves, which has its own spatial jump cuts.

Jonas Wood, Snowscape with Barn, 2017, oil and acrylic on canvas, 106 x 120 in., Dallas Museum of Art, TWO x TWO for AIDS and Art Fund, 2018.22, courtesy the artist and David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles, photographer credit: Brian Forrest

Snowscape with Barn (2017), the only scene in which the outdoors seems even somewhat harsh, harks back to the artist’s New England childhood and features a horizontal line, about two-thirds of the way up the canvas, that neatly slices the bare trees with their snow-covered boughs so that the trunks above the line seldom meet up with those below. Wood’s idea of dicing and splicing space, while derived from analogue modes such as the photography and collage that he reportedly uses in his studio process, arguably relates just as much to Photoshop, or even that corollary of the digital image, the glitch. As a visual metaphor for contemporary ways of seeing and of experiencing reality, Wood’s spatial montage feels understated, or possibly even slight, but as the only disjunctive element in otherwise pleasantly unremarkable images painted in a friendly, cartoony manner, it assumes outsize importance.

Jonas Wood, Clipping A2, 2013, oil and acrylic on canvas, 118 x 93 in., private collection, courtesy the artist and Anton Kern Gallery, New York, photographer credit: Brian Forrest

Other galleries in the exhibition hold similarly likable works: self-portraits and portraits of friends and relatives, some based on vintage family photos; studio still lifes; and a room of “Clippings,” oversized childlike depictions of individual stems of the houseplants Wood portrays so prolifically, inexplicably hung on the artist’s wallpaper printed with an allover grid of wonky green tennis balls. Given the almost aggressive blandness of so much of the artist’s subject matter coupled with the relatively generic facture of the paintings, we might find ourselves a bit hard-pressed to know exactly what to make of this show or why the museum has chosen to anoint Wood with its institutional imprimatur (save for that part about auction prices and collectors). Wood lacks the flash and urgency of some of his peers, the virtuosic brilliance of Dana Schutz’s fantastical allegories of society and the psyche, for instance, or the social consciousness of Nina Chanel Abney’s filtering of the Black Lives Matter moment through the jazzy syncopations of Stuart Davis. Even younger artists — say, Louis Fratino and his deployment of Marc Chagall to channel a kind of oppositional queer tenderness — might appear more compelling choices for the full museum treatment.

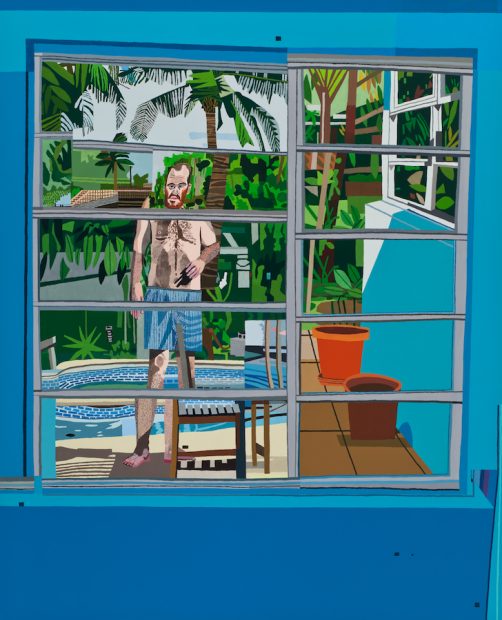

Jonas Wood, Calais Drive, 2012, oil and acrylic on canvas, 104 x 84 in., Yusaku Maezawa Collection, Chiba, Japan, courtesy the artist and David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles, photographer credit: Brian Forrest

The exhibition’s introductory wall text declares that Wood’s art “speaks to universal preoccupations: our relationship to family, to our heroes, to our past and future, as well as to how we see the world and how the world sees us.” So we may well ask how universal Wood’s preoccupations really are? Since at least the 1990s, we have regarded the subject position of the artist as a key factor in the interpretation of the work, and, as the examples of Wood’s colleagues I have chosen above suggest, gender, sexuality, and ethnic identity figure heavily in our assessment of contemporary figurative painting — except, of course, when it comes to the “universal preoccupations” of straight white men. (The impact of Schutz’s identity as a straight white woman upon the reception of certain of her works is a story for another time.) If we look at the exhibition with this in mind, however, we can see Wood’s paintings as expressions of his own identity, as much as those of any other artist. Middle-class comforts and heteronormative nuclear families abound, as does a certain self-regard, as seen in the self-portraits, such as the enormous, Hockneyesque canvas The Hypnotist (2011), which shows, across its nine-by-fourteen-foot expanse, the artist indulging in a therapy session. Confessional at this scale can come across as smugness.

Jonas Wood, Night Bloom Still Life, 2015, oil and acrylic on canvas, 90 x 80 in., Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; gift of Linda Macklowe, 2016.124, courtesy the artist and Gagosian, photographer credit: Brian Forrest

As for heroes, Wood’s are other artists. He pictured Philip Guston in a smallish portrait from 2006, and in Spiritual Warrior, a larger canvas from ten years later, limned his hunky shirtless bestie Mark Grotjahn, a painter whose own straight white maleness became an issue last year when he chose to publicly decline being honored at a gala at MOCA in Los Angeles because of the lack of diversity of the previous honorees. To be fair, the exhibition also includes portraits of artists of color, but, oddly, the artist to whom we imagine Wood should feel closest — his wife, the Japanese American ceramist Shio Kusaka — never appears in the paintings on view. Her ceramics do, though, and, in a curious circumstance, the Freudian implications of which I will leave to others, Wood seems to represent his partner and mother of his child only by a series of empty vessels.

Jonas Wood, Sears Family Portrait, 2011, oil and acrylic on linen, 44 x 32 in., private collection, courtesy the artist and Anton Kern Gallery, New York, photographer credit: Thomas Müller

Some evidence suggests that Wood may possess an inkling of awareness of at least his own thematization of whiteness. The Bat/Bar Mitzvah Weekend (2016) enlarges a 1990 family photo of the artist at thirteen with his family, the Jewishness invoked by the title the only signifier of an ethnicity once seen as “other,” but that in America has long since assimilated with white. Yet this and the adjacent Sears Family Portrait (2011) portray Wood’s parents and siblings — and the artist himself — with such ungainly, unattractive, nearly cretinous miens that they manage to evoke Goya’s devastatingly unflattering portraits of the Spanish royal family.

Viewing Wood’s work through the lens of straight white male identity certainly seems to reveal unexpected, cringeworthy, and possibly less triumphal aspects of his practice, which probably explains why such a thing so seldom occurs. But the exhibition acknowledges none of these. Our public museums have an obligation to strip away the veils of various sorts of obscurantist hegemonies in order to assess art for what it is. Or they should. Institutions like the DMA need to be able to move beyond untenable claims of universality and give us honest answers. Why straight white men? Why now?

Through July 14, 2019 at the Dallas Museum of Art

6 comments

I’m thinking of Christina Rees’s recent defense of Louie Anderson as Christine Baskets. I guess I’m okay with straight white guys if they are doing something remarkable. Woods really isn’t.

This piece is a must read for any painter delving into autobiography.

A lot of big words and heady criticisms it seems to me that Billy Shakes quote, much ado about nada. Too bad a lot of the pivotal pain-tings that this author describes aren’t even shown. Though some are, I don’t get it, why white why now? What does that color have to do with this artist I’ve never even heard of?

souless

Wow your “insight” into Shio only being represented via her “empty vessels” is a desperate reach while also managing to totally dismiss her work. Must we be so literal as to demand a physical profile as a source of representation? Are we really so literal that metaphor is considered a dismissal? Pretend for a moment that you could just slap her face everywhere a vessel she’s made is reproduced by Wood in a painting. How insignificant is her place in his world, now?

Being straight, white, and middle class is clearly a misunderstood identity.

I don’t understand trashing an artist’s work, good for him he had a show at the Dallas museum. Wouldn’t we all artists like that. I’m 70 years old I have spent my life creating art that maybe no one will ever get. I do it because I have no choice like many artists I know. I am old enough to know so what, let him make his own art and you make yours, F—-k the critics and no sayers do it for yourself. If you can do better then do it.