In what may be an unsubtle overcorrection after its recent turmoil with a now-former curator, the Dallas Museum of Art is currently sporting all-woman contemporary shows in three of its four quadrant galleries. And as of this last Sunday, the fourth quadrant gallery was hosting Laura Owens’ work, as part of that artist’s larger retrospective down the hall (that retrospective closed at the end of that day, after a four-month run). These four quadrant galleries flank the museum’s barrel vault space, which right now hosts a show of Impressionist and Modern paintings by the usual suspects: Renior, Degas, Picasso, et al. So for six weeks over this summer, the long barrel vault has speared, like a giant historical phallus, through four all-women shows.

This juxtaposition isn’t as interesting as it sounds, nor does it feel intentional. More on that in a minute, because I wasn’t there to see the Impressionism, though I was happy to see some of those paintings along the way. I was there for the other, woman-only shows, which it turns out are a mixed bag.

When I mention the museum’s possible stab at over-correction, I mean that the DMA late last year parted ways with its Senior Curator, Gavin Delahunty, over sexual misconduct allegations. During his four-year tenure at the DMA, Delahunty made a name for himself with a much-lauded Jackson Pollock show, but in the meantime he had been filling the barrel vault with interesting group shows taken from works in the museum’s storage. He was pulling out unlikely selections, having them polished up and restored, and grouping them in clever and unexpected ways. I’d like to think that the DMA understands that, curatorially, it has every right (if not incentive) to continue some version of this tactic, because for those of us who’ve been going to the DMA for decades, it was eye-opening and pretty terrific exposure of the museum’s pre- and post-War art collection.

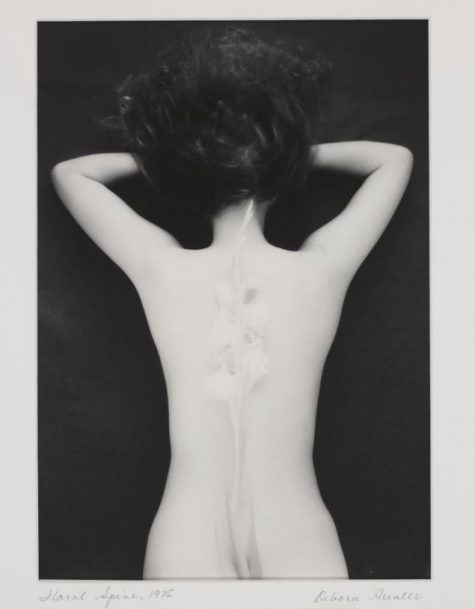

Back to the women. Two of the current quadrant gallery shows, titled Soft Focus and Body Ego, are presented as fraternal twins, and are indeed taken from the museum’s permanent collection. Most of the artists included are international, but in a nice touch, the museum has included some work by solid regional artists: Frances Bagley, Debora Hunter, Annette Lawrence, and Linda Ridgway. Soft Focus is photography, and Body Ego is sculpture, and while both showcase some really nice work by some excellent artists, including Lynda Benglis, Diane Arbus, Catherine Opie, and Eva Hesse, the latter sculpture show is by far the more convincing one.

The photography show’s press materials mention that these 20 or so woman photographers “express softened and dreamlike aspects in their pieces,” but this feels like a curatorial stretch. (There’s nothing soft about Arbus’ portraits, for example). Frankly, it feels like a dated excuse to provide a “ladies’ night” exposure to a lot of strong artists who have nothing in common — formally, technically, intellectually — other than that they all have vaginas. I really don’t mean to be crass. But I’m well aware of (and deadened by) some of the responses by institutions to this #MeToo moment, and their scrambles to get as much work by as many women out there as possible, under outmoded and half-baked pretenses. Instead of feeling celebratory or defiant, this selection feels cynical, in a kind of quota-meeting 1990s way. I didn’t like hyper-isolation of women artists back then, when I first started covering art, and I don’t like it now. When the curation feels this arbitrary, it’s insulting to the artists, which is the opposite of what should be happening to the artwork of women right now.

Yet just across the walkway, the Body Ego show of sculptures feels remarkably coherent and robust. All of the works directly or indirectly allude to the human body (though very abstracted) and the range of artists’ methods in getting there is compelling. Taken together, we have a show that’s practically building a Frankenstein’s monster of a whole human, with an emphasis on options for orifaces: Hannah Wilke’s chewing gum (mouth, genitalia); Hesse’s brick of ominous stacked latex (flayed skin) and Benglis’ floor piece (body fluids); Ridgways’s bronze spine of connected orbs; Isa Genzken’s cracked-open brick room (again, oriface); Bagley’s unsettlingly outsized fist/mouth/pussy atop atrophied “legs.” I’m taken with Heide Fasnacht’s rubber laminate and steel Witness (1990). I don’t recall seeing it before. It never surprises me when any artist makes work around the subject of the corporeal, and in fact I think that in terms of contemporary abstraction, many of the artists doing it the best over the last 40+ years just happen to be women. (Lee Bontecou and Louise Bourgeois aren’t in this show — they don’t need to be — but their spirits are.) This particular snug selection at the DMA proves my point. If you go to the museum to see anything in the next few months, make a point to see this one.

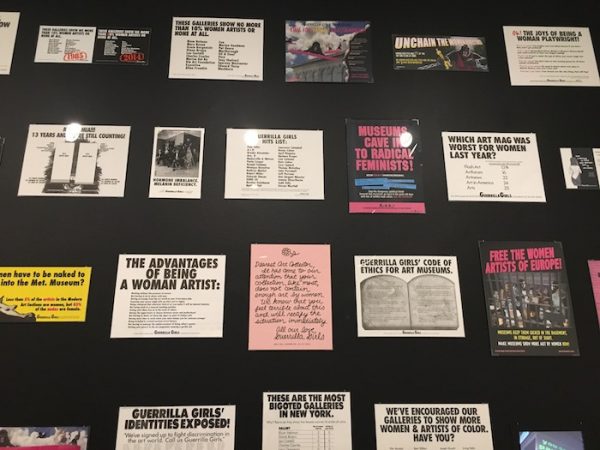

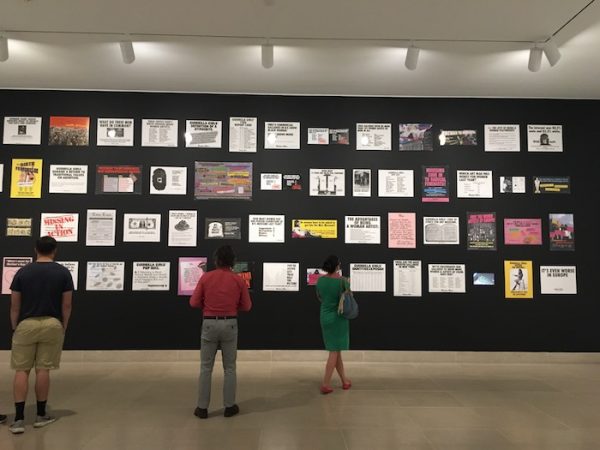

Across the vault space are the other two quadrants. In one of them, a Guerrilla Girls’ show opened last month. It’s a salon-style hang of the posters and ad campaigns by the feminist-activist group created between 1985 and 2016 to call out the art establishment on its lousy record of representing women artists in institutions and galleries. I grew up with the GG’s iconic protest art, and it’s always nice to see the anonymous group’s output, but I’ll note that it wasn’t that long ago that the Modern in Fort Worth had a very similar room (albeit more complete in its historic GG ephemera) as recently as 2015, for its Urban Theater show.

You have to traverse the barrel vault and its Impressionism show to reach any of these four quadrant galleries. Together, the five spaces make up a kind of distinct central hub in the museum, and feel inextricable to me. So the current layout is jarring, because the quadrants are in their usual austere white-box mode, but the barrel vault has been given a dissonant National Gallery treatment — dark and dramatic walls, a lot of ornate gold framing, a lot of corners to turn, a lot of furniture to sit on — for this painting show, which is all works from a collection of Dallas philanthropist Margaret McDermott. (McDermott died in May, and this show of her collection opened about a month afterward.) Not only does it not “pair” well with what’s happening in the quadrants, but it’s a pretty middling collection of paintings by some of the true greats, with a few standout works. And yet it still manages to make Owens’ paintings, which unconvincingly “fill the space” of the final quadrant gallery, look particularly slight.

Nonetheless, I like the quadrant galleries. Some people complain about the quadrants, and especially about what feels too terminal or boxed-in about them, but I think they’re well-proportioned, and unplagued by too many entrances and exits, windows and other visual interruptions. They’re intimately scaled for thoughtful, smaller group shows, like Body Ego, and just about large enough for early-to-mid-career solo exhibitions. Delahunty may be gone, but the show must go on, and the DMA would do well to proceed with checking any guilt-by-association at the door and taking a some unexpected risks or interesting off-roads with new shows, borrowed shows, and especially with its own collection. In the case of the current quadrant shows (or at least as of last Sunday), the score was, I suppose, roughly 2 out of 4.

‘Body Ego,’ ‘Soft Focus’, and ‘The Guerrilla Girls’ are on view through Sept. 9, 2018 at the Dallas Museum of Art.

1 comment

As usual, Christina offers a valuable analysis.

Because the DMA neglected collecting photography for so long their holdings lacks depth, focus, and of course gender and ethnic diversity. Curating Soft Focus was an exercise in paucity.

I can’t help but compare the world-class photography collection created by Anne Tucker at the Houston Museum of Art beginning in 1974 with the poverty of the DMA’s holdings.

In preparing for my Saturday afternoon talk at the DMA I researched just how few photographic works were in the DMA collection. Here is a more or less accurate history of photography collecting at the DMA. Robert Murdock, the DMA’s first contemporary art curator (around 1974-1980) acquired 107 photographs using funds from a Polaroid Foundation Grant. 14% of the photographs were made by women. My 1975 photograph in Soft Focus entered the collection then. Around 1998 a Friends of Photography group was formed at the DMA. I found ten photographs, all done by men, were acquired through their funds in 1998. That group existed less than five years, dying mostly due to lack of institutional support by the DMA. Over the years a small hodgepodge of photographic prints entered the collection, donated by individuals, not through concerted museum initiatives. While a few are of high quality, many of lesser quality suggest a backstory of the museum’s development courting bigger fish donations by accepting less significant ones. Most recently, the DMA finally got smart and had Gabriel Ritter go on a buying spree from 2010-2014, adding fifty “contemporary art” works, many of which incorporate photography. Maybe a third or half of the work in Soft Focus is from these recent acquisitions.

I was delighted to be included in show, but the real problem is it is near impossible to curate a tightly focused show when there was so little to choose from.