Installation view of Bryan Wheeler’s solo exhibition Slinger, at Louise Hopkins Underwood Center for the Arts.

In the short time I’ve lived in Lubbock, there have been three major exhibitions here featuring the work of Bryan Wheeler: a retrospective along with his brother Jeff’s work at the Buddy Holly Center when I first arrived in 2017; another retrospective of the brothers’ work, currently showing at Contemporary Art Museum Plainview; and a solo exhibition at LHUCA. Everyone knows the Wheeler brothers around here; they’re local legends. At the gallery talk for Bryan Wheeler’s exhibition Slinger at LHUCA, which I figured I should attend to learn more about the guy, he was given no introduction, such is his status as a local art celebrity. I couldn’t help rolling my eyes.

My dismay ended there, however, as Wheeler began to talk, describing his work and relationship to the subject matter of his latest series of large-scale paintings — the epic poem Gunslinger by Ed Dorn. Written between 1969 and 1975 over four volumes, Gunslinger is an anti-heroic, postmodern journey from El Paso to Cortez, Colorado, using the tropes of the Western to navigate the rise and decline of the counterculture and chart a retreat into the self as a site of change. I confess I’ve never read it, so Wheeler’s primer on the book’s characters and themes was welcome. Trying to glean the whole story from Wheeler’s four epic-sized paintings (one for each book), the sketches and studies, and the wall text seemed like an impossible task. I felt like if I hadn’t read the book, I just couldn’t understand the paintings in the “right” way.

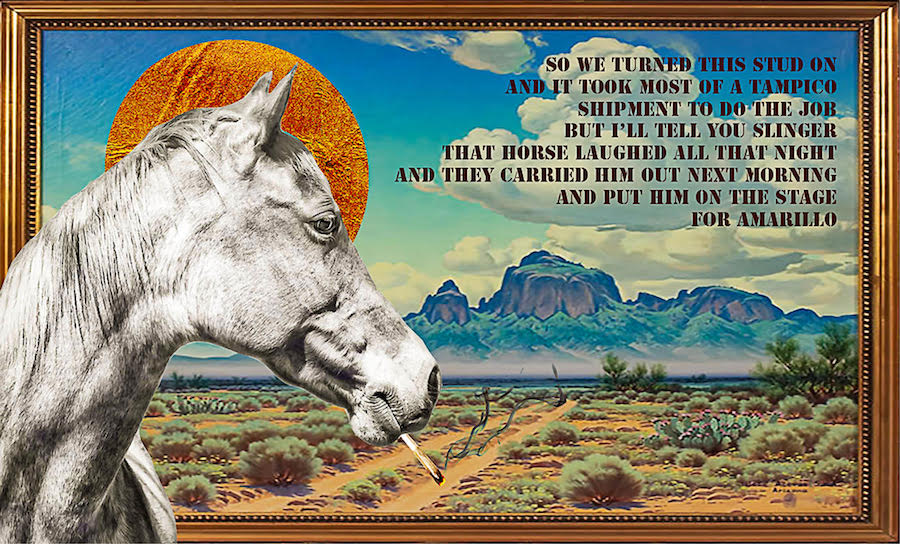

Bryan Wheeler, Universe City and Other Natural Centers of Doubletalk, archival digital drawing and collage, Book 2 Prototypes, Outtakes, and Ephemera

After the gallery talk, I still feel that way. Only someone with an intimate knowledge of Dorn’s masterwork will be able to decode the thick and layered references in Wheeler’s series. A cigarette-smoking horse; Howard Hughes; ojos calientes; a five-gallon can of LSD: all appear seemingly random in Wheeler’s paintings but point directly to characters and events in the text. I suspect that if you know the book, you would understand these paintings on a deeper level and it would probably enhance your appreciation of the artwork.

![Bryan Wheeler, Book I (1968 [THC]): The Theater of Impatience acrylic, charcoal, gold leaf, and beaver-made wood chips on panel](https://glasstire.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/unnamed-1.jpg?x88956)

Bryan Wheeler, Book I (1968 [THC]): The Theater of Impatience

acrylic, charcoal, gold leaf, and beaver-made wood chips on panel

![Bryan Wheeler, Book III (1972 [COC]): Sublime, Starring the Man acrylic, charcoal, gold leaf, and beaver-made wood chips on panel](https://glasstire.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/unnamed-1-1.jpg?x88956)

Bryan Wheeler, Book III (1972 [COC]): Sublime, Starring the Man

acrylic, charcoal, gold leaf, and beaver-made wood chips on panel

Some elements are less successful. Wheeler refers to himself in all but the last painting (where it probably didn’t fit in with the symmetrical composition), in the form of a pint of beer and a smoking cigar fitted into the grooves of an ashtray on a bar top next to a copy of Gunslinger. It comes off as a gratuitous self-indulgence, but maybe it’s in keeping with the book and the character known simply as “I”. Wheeler has also embedded wood chips in sections of each panel, but their relationship to the text and the other elements of the paintings isn’t very clear. At the gallery talk Wheeler related a story about lugging these beaver-made wood chips back from a hike to his studio, and said he included them to relate to environmental resources — but in context it doesn’t seem like more than an eye-catching gimmick.

Bryan Wheeler, Universe City and Other Natural Centers, of Doubletalk, archival digital drawing and collage, Book 2 Prototypes, Outtakes, and Ephemera

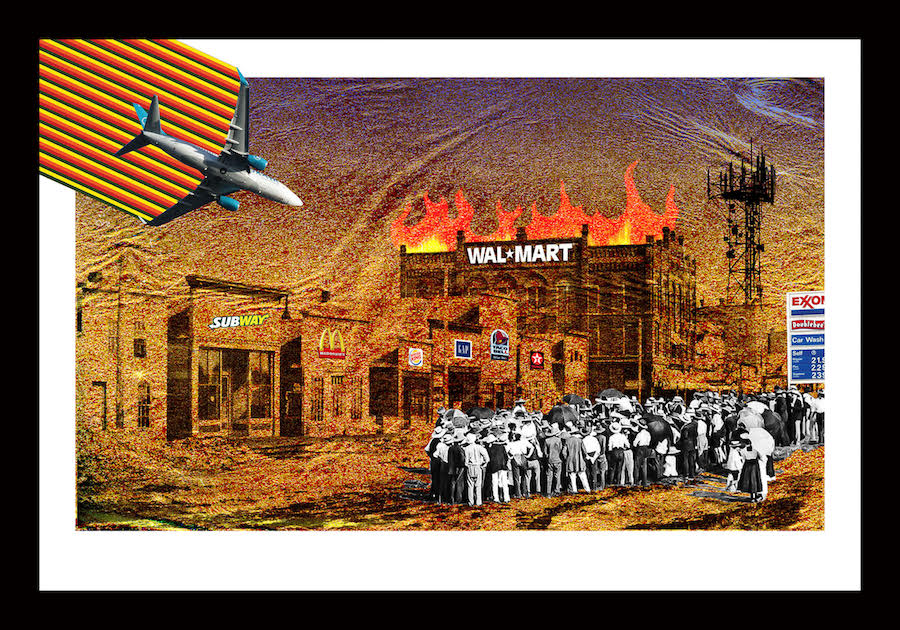

Minor quibbles aside, this series is remarkable for its ambition, rigor and depth. It’s an impressive feat of painting and poetic interpretation, and it makes sense that an artist with a PhD in art history has attempted this adaptation. The last painting, Book IIII, which was still wet when Wheeler hung it in the gallery in time for May’s First Friday Art Trail, brings the series to a close with a satisfying symmetry, centered by a man in cowboy boots sitting in a meditative pose with the sun flaring in his sunglasses. Gunslinger ends without the culminating showdown between the intellectuals and the industrialists, implying that the conflict is ever impending, with each party gaining advances and retreating in turn. A digital collage conflating Trump and Howard Hughes brings this series right into the current era.

Wheeler said that on his first reading, one line from Ed Dorn’s poem immediately stuck out and resonated with him: “The souls of old Texans / are in jeopardy in a way not common / to other men.” One of Wheeler’s goals with this series is to complicate the narrative of the Texas mythology, which extends to the mythology of America herself, the “lie of John Wayne bootstraps,” as he put it. Dorn’s poetry was undoubtedly political, and so are these paintings.

Wheeler might be a Lubbock legend, but legends are simply stories that are taken for granted. With Gunslinger, Dorn excavated the construction of a modern mythology taken for granted as mass culture. Dorn’s Gunslinger has been compared in that way with Pop Art, and that makes it a natural fit with Wheeler’s style. But while Pop’s call-outs of clichés have largely become clichéd themselves, in adopting Dorn’s poem as a subject matter, Wheeler has found a new way forward in his own work. In this passionate undertaking Wheeler has created his own epic that far exceeds the local, looking through literature, history, geography, and the imagination to the long horizons of our past and our future.

Through June 1, 2019 at LHUCA, Lubbock