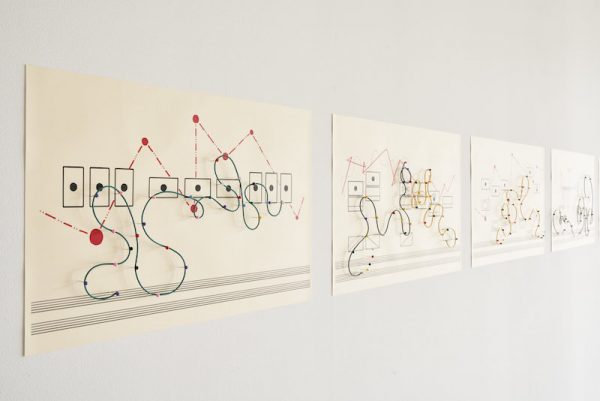

Installation shot from Steve Parker’s WAR TUBA RECITAL at Big Medium in Austin. All photography: Sarah Frankie Linder

In one archival photograph from the U.S. Naval Air Service, a man stands between two giant horns — their diaphragms are several feet in diameter — with a pair of long, skinny tubes snaking into his ears. He’s trying to hear what he knows he can’t see. This is a “war tuba,” a WWI-era acoustic detection and early-warning system. (The first practical radar systems weren’t perfected until the mid-1930s).

Steve Parker’s solo exhibition WAR TUBA RECITAL, open through November 18 at Big Medium’s Austin gallery, takes the idea of the militarization of sound as its starting point, and in just six artworks explodes it outward into an impressive variety of gestures and influences, from Dr. Seuss and John Cage to the psychoacoustics of stereo separation.

The titular war tuba appears feet from the gallery door in the form of two sousaphones; PVC tubing snakes from their mouthpieces toward a minimalist headpiece. Like a pair of comically large ear trumpets, the bells amplify every sonic detail from the gallery and the street outside: traffic; speech; footsteps; even the ambience of the A/C is (re)claimed as alien resonance, or even music. WAR TUBA is part instrument, part conduit, part sculpture. It sets the tone (so to speak) for the balancing act achieved by every part of Parker’s rigorously-researched show, which simultaneously positions sound as threat (marching-band crowd frenzy; sound cannons; enemy aircraft triangulation), and therapy (deep-listening; meditation; sound baths). What endangers can also entice. The same sirens that warn citizens to go into hiding also spread the announcement that it’s safe to come out.

Parker’s playful gestures don’t undermine the show’s emotional impact. This is most evident in the many-headed piece Sirens, which occupies the middle of the gallery. Every 15 minutes, a dandelion’s head of busted trumpets —“BAD BELL” is scrawled across one’s mouth — plays “songs of distress,” adding an additional layered song at each interval. The songs include more than one rendition of You Are My Sunshine, the song children sang in the ’50s and ’60s during tornado drills. To hear it in this setting strikes a horror-movie chord (It’s Raining, It’s Pouring recently played on a real-life siren, to similar effect), but it’s also immensely pleasurable to hear a rogue burst of song in a gallery space.

The delightful Ghost Radio is a touch-activated sculpture that uses skin conductance to trigger sound samples of Morse code, signal-jamming Chinese opera, and “coded songs from the Underground Railroad.” It also strikes a balance between profundity and levity, and manages (as do all of Parker’s pieces) to combine disparate referents without feeling like an arbitrary collage. Ghost Radio, like WAR TUBA, is undeniably fun to play with and fun to look at — a Cornelius Cardew-inspired graphical score of colorful wires zigzags to a tidy suitcase, housing a micro-controller — and anyone who cares to delve beneath its surface will find a wealth of deeply considered ideas about communication, vulnerability, violence, power, and authority.

Another of my favorite pieces, ASMR Étude, presents another set of bizarre ear trumpets, this time anchored with construction-grade isolation headphones, which invite visitors to walk along a series of small black speaker drivers that span the entire back wall of the gallery. Each driver plays a different set of ASMR samples — soft, gentle, human sounds that trigger “brain-tingling” sensations of relaxation in some people — which shift depending on the listener’s distance, orientation, and movement. There are fingernail-taps, mouth clicks, whispers, rustles. (ASMR stands for “autonomous sensory meridian response” and such sounds have been found to have therapeutic effects, even for the treatment of PTSD, which afflicts more than 10% of war veterans.)

But beyond its thematic appropriateness, Parker’s ASMR Étude is a study of what it means to be an artist in the first place. An étude is usually focused on training or demonstrating a single technique — more an exercise than a fully fleshed-out composition — but here the singular visual impact of the drivers carries synecdochic weight. Walking me around the gallery hours before the opening, Parker repeatedly referred to the people who produced his Étude samples as “ASMR artists” — performance artists and musicians in their own right, even if they haven’t been accepted as artists in mainstream culture. Further: the passive, static recordings only come to life when the listener approaches, and each listener will interact with the wall in a different way, by chance (how tall are you?) and by choice (where will you stand, and for how long?). It’s as much a choreographic score performed by the listener as it is a “sound art” installation.

This participatory element is characteristic of Parker’s oeuvre; many of his previous works are orchestrated in public. It’s a joy to see him take these ideas to the often hyper-controlled realm of the gallery. Anyone who sets foot in this exhibition contributes to it. And Parker’s respect for less-conventional art forms is evident in every piece in this show. Parker shows the same tongue-in-cheek solemnity and deep respect for all of his sources — whether it’s someone tapping their fingernails on a niche YouTube channel, or Dr. Seuss, or the distress-song singers, or the historical giants of experimental music like Pauline Oliveros, John Cage, and Cardew.

WAR TUBA RECITAL is a commanding, absorbing show. For me, it wobbles only in its title, which suggests a kind of set program or a systematic cataloguing, or a Homeric litany. Instead, Parker offers us something much greater: a sense of how our own attentiveness conducts and transforms the world around us. The generosity and respect with which Parker forms his connections — sonic, sculptural, conceptual — always includes his audience, and always invites them to create their own.

Through Nov. 18, 2018 at Big Medium in Austin.

Photography by Sarah Frankie Linder