Note: The following is the prizewinning entry of the inaugural Glasstire Art Writing Prize, which was open to college students in the North Texas region. Melanie Shi is a philosophy major at the University of North Texas in Denton.

(All photos by Melanie Shi)

It is a cloudy, gray, and serious September evening when I visit James Turrell’s The Color Inside (2013), in Austin. It has been rainier than usual as of late — the first day of autumn, two days until the full moon. I have recently relocated to North Texas from New York, where the landscape heralds the arrival of the season with rapidly metamorphosing foliage, a breeze on the Hudson, and crisp air. I do not yet know what fall in Texas will bring, besides tornadoes. But on my drive south along I-35 there are long country roads, rows of telephone poles, gas stations, oak, sycamore.

When I arrive, the light sequence — Turrell coordinates changes in light within darkened, minimalistic spaces like this rooftop aperture — begins, soundlessly, sometime between 7:00 and 7:03 pm. My watch, with its optimistic second hand, seems to miss the point: Eternity passes between the moment the attendant shuts the door, and the moment I whisper to my friend sitting to my right (I’ve made one friend since I’ve moved, and we’ve taken a road trip to see the sky): “Is it me, or did that pink just change color?”

The Color Inside, one of Turrell’s more than 80 ‘Skyspaces’ located all over the world, is a kind of giant, inhabitable plaster eye at the center of UT’s Austin campus. Situated atop the third floor of the Student Activity Center, it consists of an ovoid space with black basalt benches that wrap around a center of tile flooring, directing viewers to look up to an open oculus — oval, with no glass — that lets in light from the sky. The sharp-edged oculus is the focal point of the light-filled cove, which is reduced to its simplest architectural elements to encourage seeing in its purest form. Inside this “sensing space” — what Turrell terms his chamber — hidden computer-controlled LED lights circling the aperture cycle through color effects. Interactions between the LED and natural light outside generate dynamic changes in color, in hour-long periods, at dawn and dusk every day.

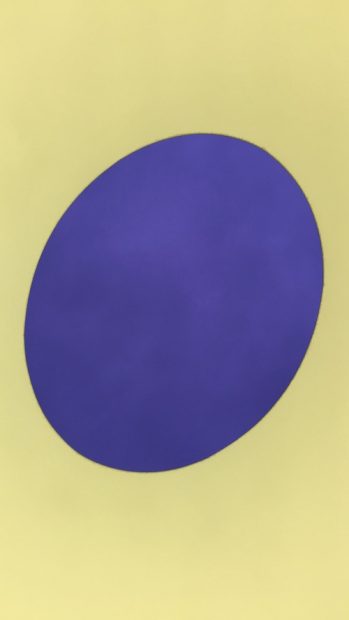

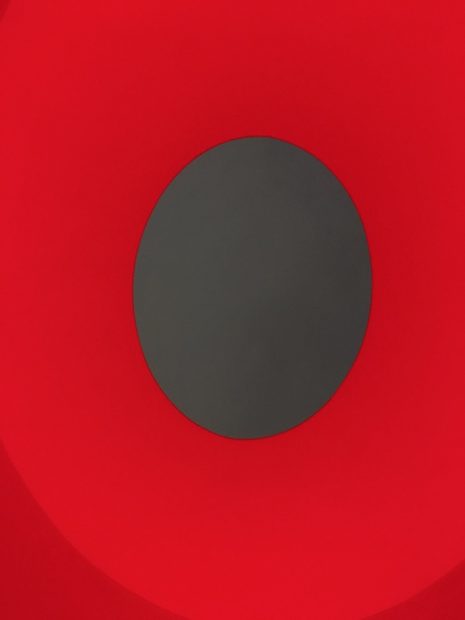

During these sunrise and sunset sequences, the oculus makes visible the act of seeing itself, breaking the light of the changing sky into waves of transmutating hues that each viewer perceives differently. As the sun shifts its angle, and clouds drift in and out of the horizon, the eye and the space itself cycle through brilliant combinations of color — of slate-gray sky, and a chamber lit in salmon, indigo and amber; sea-foam green paired with a translucent, almost white sky overhead. For awhile the colors seem to segue at an even pace, but toward the end of an hour, they move faster, and feel like they’re speeding up time itself. In certain combinations, the oval sky appears to wriggle, expand, and even spring forward toward the viewers in the space.

The exact nature of the optical effect depends on the day’s weather conditions and on the position of the person seeing. For me, the sky seemed to emanate out from itself; the chamber was red while the sky surged toward me in psychedelic blue. For my friend, the sky looked gray (so goes the sunset on a cloudy evening) and the surrounding cavity walls a bright, stripy, tiger orange.

The experience of the work is at once communal — the room can house around 25 people at a time, and we all bask in the same light sequence — and intensely private: No one person sees the same light, and no one sunset produces the same combinations of color. Such is the nature of seeing, Turrell suggests: We live in a reality of our own creation, caught in a space somewhere between the eye and the mind. Our vision is always subject to sensory limitations and to our personal biases of seeing. It is impossible to see the same thing twice, or for two people to see exactly eye-to-eye.

****

As I watched Turrell’s light sequence unfold in a silent rhapsody of color, I could not help but notice the sounds of deafening cheers coming from the nearby Darrell K Royal-Texas Memorial Stadium. It was the night of a TCU vs. Longhorn football game — UT-area streets were jammed with cars bleeding school spirit and saccharine, beat-heavy electronic music. On the way to the Skyspace, we had walked past the stadium, with its seating capacity of 100,119 people. The school had recently announced $175 million projected cost for a future expansion of the south end zone. On the way to see the Turrell, I remember thinking how eerily similar the stadium and his installation are — that the stadium is another kind of opening to the sky, a crater in the earth. From our vantage point, the spectators in the stands appeared more like abstractions than people, their bodies blurred indistinctly into a pointillist series of burnt orange, white, and purple dots. Pure noise emanated from the stadium’s center, rendering everything around mute in comparison. But in the Skyspace, I could hear every breath, murmur, scratch, and sneeze of the people around me. Nobody told us we couldn’t, but nobody spoke.

As I gazed upward at Turrell’s oculus, my back on a blanket, I tried to recall the last time I’d laid down to observe and watch the sky. How long had it been since I concentrated on one thing for several hours with no interruptions, or simply sat with nothing on my mind? While I watched the eye, I started to remember what my consciousness felt like before I ever owned a smartphone, amusing myself on 17-hour flights to China; I remembered lying in the aggressive Bermuda grass in my childhood backyard, and the first times I ever lost my sense of time from energized focus (what is termed, in positive psychology, as ‘flow’) — searching intently for books at the public library, practicing the piano, writing. “What is important to me is to create an experience of wordless thought,” Turrell has said. “I was thinking about what you see inside, and inside the sky, and what the sky holds within it that we don’t see the possibility of in our regular life.”

In our modern way of living that values productivity and forward advancement via technology, it’s sometimes difficult to justify taking out an hour in an evening just to watch the sun set. Turrell’s The Color Inside offers this experience, and reminds us of why it is important. It encourages the viewer to reflect — to reflect on reflection, and to notice the very essence of how she is seeing. It does so using only the play of light and the viewer’s vision, yet suggests that an artwork can be an event instead just a material thing. In fact, it can only be experienced in person.

There were at least five parties of people in the Skyspace together that night. Some, like my friend and I, had come in pairs; one was a party of four; and one particularly blue-eyed boy appeared alone. He left sometime in the middle of the sequence, and shortly after returned wearing headphones. By the time we exited that night, the oculus and chamber had turned indisputably black and white, yet the boy remained on the ground. I wondered if I should speak to him, but decided to leave him be, looking at the stars.

1 comment

Excellent. Well-deserved award!