What’s in a word?

Give it to Kay Rosen, and a word speaks volumes.

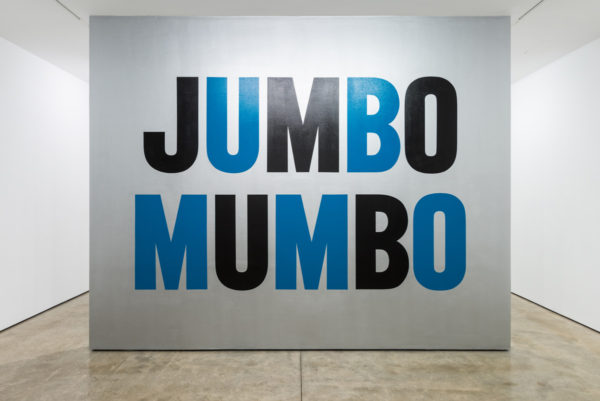

Walking into Kay Rosen’s solo show at Lora Reynolds in Austin, I was taken (of course) by the wall-size mural to the left reading “JUMBO MUMBO.” My immediate thoughts moved from the pleasure of seeing this funny saying reversed to the freaky circus our world has become. Still later, it made me think about how we’re all in this gumbo together, with the burner under the pot slowly getting hotter. What seems so simple and amusing at first is open to deeper responses and thoughts. That’s how Rosen’s art works, and even more so in person, where the hand-painted words and their flood of associations will make you feel like you’re having a conversation.

The Jumbo Mumbo mural is titled Big Talk, as is the show, and that seems custom-made for the current state of affairs in this country. Yet the work is dated 1985/2004. Rosen’s work seems to speak for the ages, and one’s response to it can shift and change over time as the context swirling around it settles into the present moment.

Rosen, a native of Corpus Christi, left Texas for college. While her career is based out of New York City, she has lived and worked in Gary, Indiana for more than four decades, making work that has ended up in museums and collections around the world. A linguist by training, Rosen is known for her word paintings, framed or mural scale. At first glance, they recall typography and the history of sign painting. But the sense of the hand-made is one of many subtle decisions that Rosen layers into the work. Highly inventive within a seemingly narrow construct, Rosen’s art — using one or two words — is philosophical in nature, and comments on the ever-shifting state of our culture, our history and our politics. The show on the whole is a dialogue about how we are human, how we communicate, the society we have created, and the possibilities of where we’re heading.

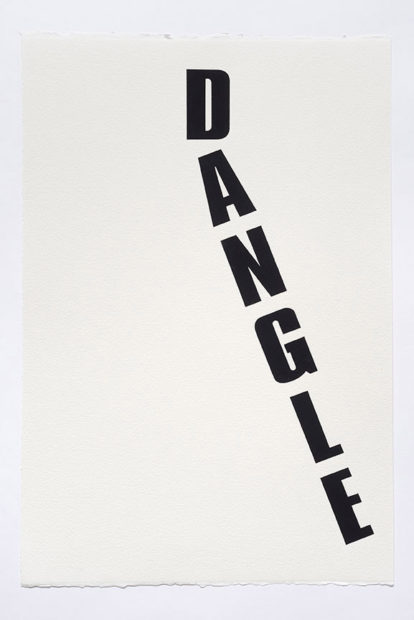

Rosen communicates with precision. The work engages our conscious minds as well as our subliminal senses and responses. Words do have parts — syllables are pronounced with more or less emphasis, bringing voice and sound into the conversation, and by breaking words out of a conventional lineup or display and playing with their layout, Rosen creates a new architecture full of meaning and resonance.

Barking Up the Wrong Tree, for example, creates a synesthesia of a dog barking and looking up at the canopy of a tree. But visually, the “bark” that grows on this tree is misplaced: it’s upside down. This simple reversal opens up new ways of looking at something familiar, and creates a new thought pattern in the viewer.

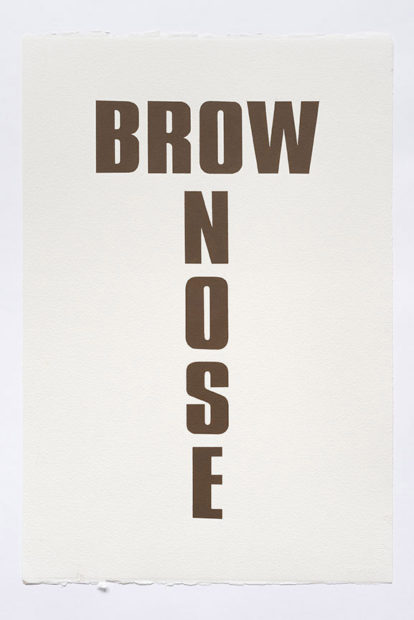

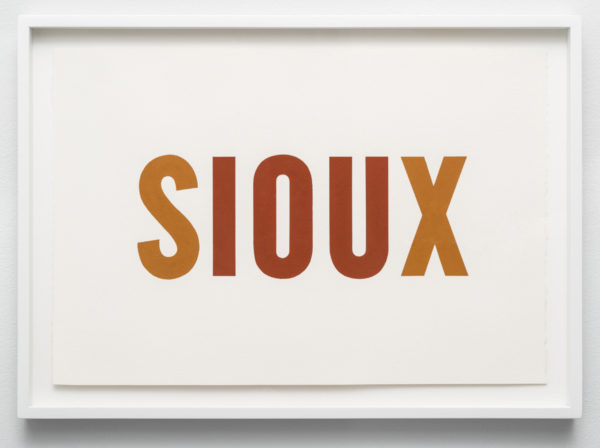

At the show’s opening reception, Rosen talked about the words as physical bodies. And looking around, I could see that everywhere in her work. The body may be a disembodied voice speaking in the mural Removal from Office (REMOVAL), or it may be an individual face in BrowNose. And it is a collective body in I Owe You (SIOUX).

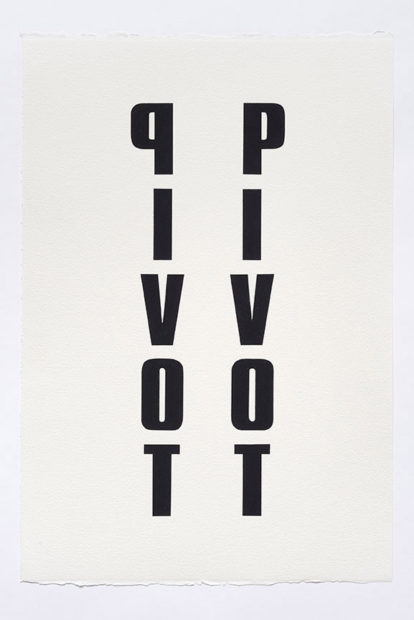

It was easy to see the word Pivot as a person. In it there are two hand-painted columns made of nearly identical letters. The ‘P’ at the top of the stack of mirror-image letters easily forms a head; there’s a chin and a neck. The heads are looking in opposite directions — one within the natural order, and one as unnatural for a word as the upside down bark of a tree or a Jumbo Mumbo world. And “pivot” is a word with complex meanings. Are these two bodies — or one conflicted pivoting body — protecting the other’s back, or are these bodies turning away from and opposing each other?

The dictionary gives more specific definitions for pivot, from which it is easy to extrapolate and play: to turn on a pin, or a central point. It describes movement. “A mechanism on which all else turns,” and, “A person or people about whom the body of troops wheels” describes the dynamic of leader and community, acting in concert. These meanings are all key to Rosen’s work; many of her words resonate with what we have done historically as a culture, and they call up how different communities coexist — at times uneasily — as a nation. Subliminally, we identify with Rosen’s bodies and their gestures.

That is especially disturbing in Dangle. It’s funny at first — an angle is literally created by separating the parts from the whole. But when one reads the word as having a head, the horrific history of lynching in our culture comes to my mind. This reading is my own, and everyone brings their own experience to this conversation, but: Just who is this person, twisting in the wind?

There are no easy answers, or answers at all. Rosen’s work communicates in complex ways. You don’t get it all in one take and move on. Her words take time, and then stay with you.

Through Nov. 25 at Lora Reynolds Gallery, Austin.