When I walked into the Ed Atkins screening room at Ballroom Marfa during Chinati Weekend recently, within seconds of the in-progress video I was asking myself: How did he make that decision? And that one? And that one? I felt myself watching, on the big screen, the brain matter of someone who’s wired completely differently from me in terms of output, and yet whose work drew me in immediately and made me want to learn his visual language as quickly as possible. It felt urgent. The video itself wasn’t demanding a rush job. My desire to go where Atkins was leading me was, though, and it was thrilling.

In those first minutes with the video, called Even Pricks and made in 2013, I understood that Atkins didn’t make that piece for me, or probably anyone in any sense of pandering, and yet he managed to make something that gets to a lot of people in an almost indescribable way. Atkins has been a go-to favorite of curators for a while now, and in his case, no one has reason to complain. For those of us susceptible to video, his work is undeniable. (Another somewhat recent example of a young artist forging a singular vision with an invented visual language is, of course, Ryan Trecartin, though these two approach the digital world so differently you can’t compare the artists directly, other than as wunderkinds of the medium who make unmarketable videos that resonate with a large swath of the art world.)

Atkins’ images, which unfurl and flicker in a kind of methodical, episodic rhythm, are 100% CGI. There isn’t a pixel in them Atkins hasn’t essentially created from scratch, and this dreamlike surrealism runs beyond the intentional into something else: I want to call his work post-verbal, but as narrative it might actually be pre-received, or pre-processed. I mean that because we live with images on screen all the time and have for years, our instinct for Atkins is already in our blood, even if our ability to describe his intention isn’t yet fully formed. We internet addicts of a specific vintage—I mean we who’ve straddled a world both with and without personal computers—can locate Atkins’ fake-real markers well enough. Here it’s rendered human hands, a chimpanzee, leaves, water, sky, a bed. The insistent, grabby text frames look hokey and familiar, too. Thus we automatically understand that something is happening here we might recognize. That’s what hooks us, and our hunger to realize his pattern of communication is engaged like a heat-seeking missile.

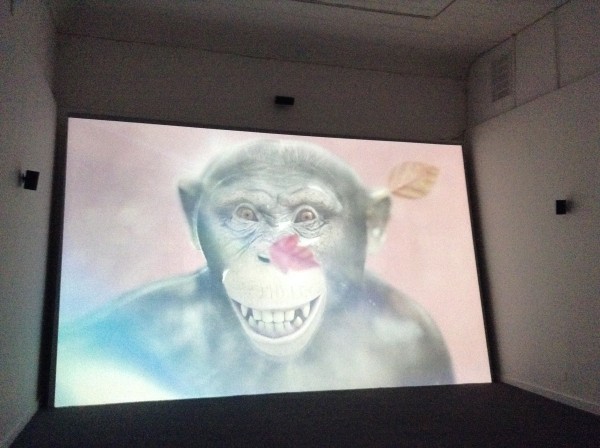

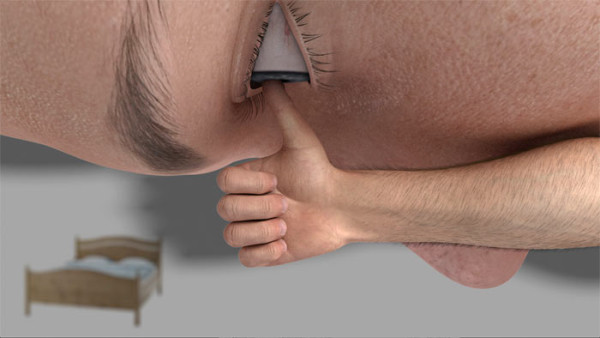

Even Pricks is sort of an homage to the repeating loss and gain of an erection—metaphorical or not—as mediated through all the stimuli we humans sort through and judge and despair of throughout the course of any quotidian day. The erection here is the (now nearly as familiar) thumbs up/thumbs down—sliding in and out of frame as a pale, disembodied man’s arm. It pokes up into a floating eye and nostril, and down into a human navel. It’s doused with fluids and submerged. The thumb inflates and deflates, over various backdrops of crumbling structures and hazy rooms. At one point, a very real-looking chimp delivers a string of spoken words in a crisp English accent. His assertive thumbs-up makes an appearance as well.

Web surfers also tend to talk about the creepiness and delights of the “uncanny valley”—the problem that comes with creating ‘realistic’ living creatures via impersonal technology—but Atkins plays on our perceptions of the human versus non-human with a knowing agility. What’s happening on screen is cold, funny, true, and grief-stricken, and this mix is something that doesn’t spring spontaneously from any silicon chip. When we watch Atkins’ work, we’re seeing a flat plane of artifice, but we’re feeling something like very real loss and longing.

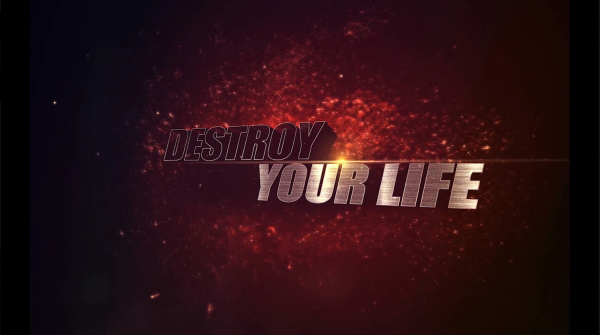

Shifts in lighting, speed, focus, depth of field: these camera tricks (which are digitally faked of course) morph and layer constantly, though in a relaxed way, and the whole is interspersed with the text interruptions (or promises) evoking straight-to-video action-movie trailers and late-night ‘90s infomercials. Some of Atkins’ visual vocabulary here is already dated, and that feels intentional. The deliberate clunkiness serves as a reminder that the ghost in this machine is a fallible, awkward, aspiring… human. Atkins has built in the dumb flaws. It makes his message around the kind of sterile, digital depravity we rinse and repeat every day all the more melancholy, so that his CGI feels weirdly if not amusingly mundane, even if his unspooling of images—and again, his decision around each decision—is completely exotic to us. Remarkably, as you watch it, his meaning clicks into place.

One of Atkins’ pieces, Warm, Warm, Warm Spring Mouths (2013), is up now at the Dallas Museum of Art for another few weeks, as part of the museum’s ongoing video series Mirror Stage. Like the Marfa presentation, it’s one giant screen on one wall dominating the dark room, along with a great sound system. I think this is the only way people should see and hear an Atkins work. I wouldn’t want to link to any of the clips online (bootlegs and trailers, et. al.) because the experience of them on a small screen is degraded and downright castrated. It’s just wrong.

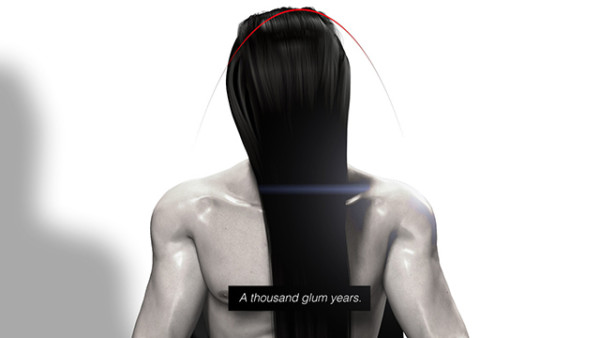

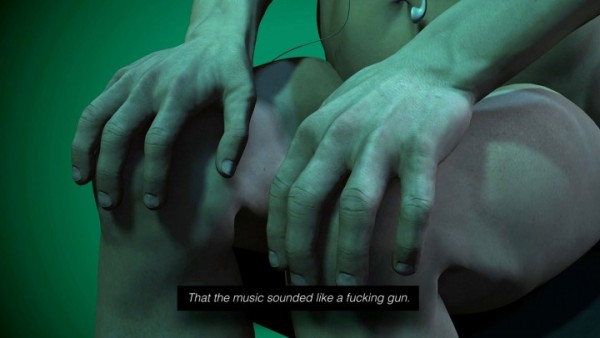

Spring Mouths is seductive and sometimes funny, too, though the onscreen human avatar/surrogate is more present and realized, and the power of the video’s spoken soundtrack is more pronounced and muscular: with this, you get the feeling right away that one of Atkins’ many strengths as an artists is his way with words—both his own and borrowed ones. Here he uses a brief spoken passage (describing a memory and a loss) as a the work’s refrain—the video’s chorus—and this makes the whole work rise and fall musically. (The bridge, then, is a quick and pointed verbal takedown of Christopher Nolan’s movie Inception, though the movie isn’t named.) He’s added a vinyl-record crackling to the audio for parts of it as well; another tease around his collapsing of the boundary between the digital and the real, or the poses we use to trick ourselves into thinking the digital can be a stand-in for the physical.

In Even Pricks, the most consistent part of the soundtrack—behind the ebb and flow of “emotionally charged,” i.e. recognizably manipulative music (which is often aborted mid-swell)—is the sound of skin slapping against skin. It’s almost constant, like a metronome. Some people probably hear it as a handclap.

I didn’t. And I loved that. Atkins knows that as he’s showing us consequences of the dehumanizing effects of technology, his own digital mitigation is re-grounding us in something like empathy. But he lets us find that in the work on our own time. Nothing about Atkins’ work is explicit. It’s one of the best examples of an artist being comfortable with the gray area that I’ve seen in a long time.

Ed Atkins is on at the DMA through Nov. 8, and Ballroom Marfa as part of its Äppärät group show through Feb. 14.

1 comment

They are amazing in their “simple” difference .