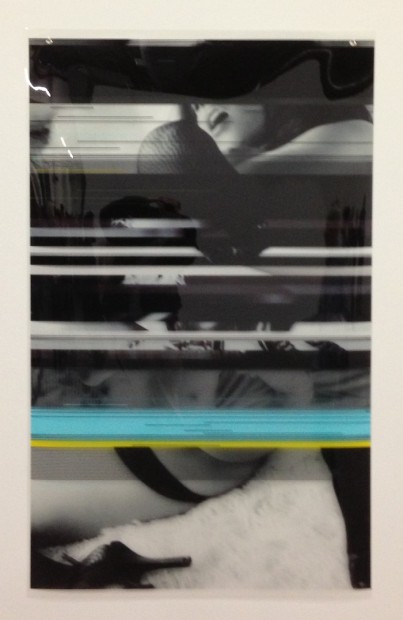

The Dallas Contemporary is a hangar and tends to dwarf anything smaller than a DC-10 that’s parked there. John Pomara’s transparent tapestries were no exception. Though they were six feet tall, looking at this row of glossy, dark images from thirty feet and more away was like squinting at a strip of photo negatives.

Or maybe more like a strip cut from a grainy 16mm stag film: Hidden behind layers of stripes and striations were softcore black-and-white porn pictures. The striations coyly obscure the mildly naughty pics like digital static or partially drawn window blinds, recapitulating the endless teasing hide-and-seek of commercial media.

About a mile from the entrance, on the back wall of the gallery, Pomara’s bid to fill the unfillable space forced him into a desperate expedient. A wall graphic of graded stripes adds little but wayfinding to the show, but gets the job done: leading viewers around the corner to see a video projection much like the still images, unfortunately washed out to the point of insignificance by ambient light spilling over from the gallery.

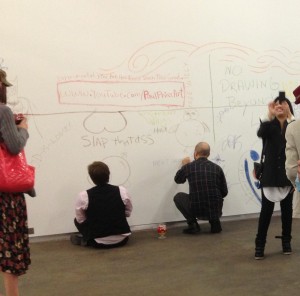

SONER, a Dallas graffiti artist, took the DC-10 approach, creating a single enormous mural in the Dallas Contemporary’s other cavernous space. Piled high with effects like a superbowl party nacho, SONER’s bubbling, neon, mutant-cyborg logotype was impossible to ignore for the six seconds it would have taken to drive by the piece were it painted on a freeway underpass; but after that, the piece, having shot its wad, was easy to ignore. Like Pomara, SONER was, despite his best efforts, faced with an enormous empty reach of white gallery wall, and, like Pomara, he fell back on a desperate expedient: Visitors were invited to write or draw on the big wall opposite his mega-tag with tiny pieces of colored chalk, producing a long wall of pathetically faint, disorganized scribblings. It was almost as if SONER was taunting viewers by providing inadequate tools. I wanted a ladder and a spray can.

Playtime, children! Today we’re going to be creative! We’re going to be drawing on the walls!

But the really big draw at the Dallas Contemporary was Caja Dallas, or SEVEN Dallas, or Caja Dallas by SEVEN, depending on which press release you got. A consortium of seven galleries, mostly from New York, rented a smaller (but still respectably sized) gallery at the Dallas Contemporary for a pop-up art fair.

The Dallas Art Fair, which co-sponsored the mini-fair, tended to talk about it as a unique project, Caja Dallas, curated by the SEVEN group. It was described as a “pioneering collective project,” a piece of avant-garde art marketing in conjunction with the main fair. After the event opened on Wednesday, the SEVEN tended to refer to the event as SEVEN Dallas, a semi-autonomous reprise of their successful SEVEN Miami event.

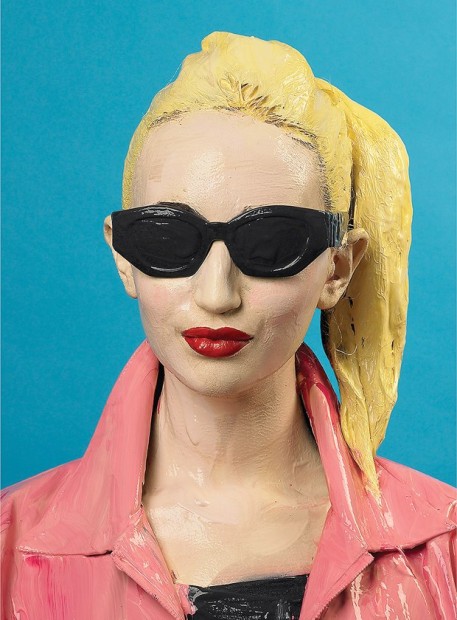

The mini-fair was hung as a single group show, mimicking just the sort of loosely curated, slightly hip, ambitious omnibus show of younger artists that a space like the Dallas Contemporary might actually mount, if they took the time to curate it, and spent the money to assemble the work from far-flung studios across the world. They might call it something noncommittal like “27 to Watch” or “Younger Than Jesus II.” Were it truly not-for-profit, it would likely include a lot more video and installation work; but with party conversations in trend-conscious collectors’ homes in mind, the show tended towards brash baubles like the above jewelled antlers by Marc Swanson, and Boo Ritson’s big photographs of stickily alluring models slathered in drippy paint. It probably contained work I ought to have found more interesting than the general run of the main art fair, but my art-viewing capacity had been reached earlier in the day, and I took no pictures. Sorry.

Boo Ritson’s Cindy-Rae (2007)

Strangely enough, the show I liked best, and thought most about, was Belgian designer Walter van Beirendonck‘s collection of men’s fashions, occupying the place of honor in the DC’s smallest and most manageable gallery. Two groupings of mannequins on motorized, cylindrical pedestals rotated slowly like well-dressed rotisserie chickens. The “fall” collection included tailored suits in parti-colored fabrics (reminiscent of Rene Magritte and Stanley Kubrick’s “Clockwork Orange”), hairy sweaters and a pair of dramatic green leather waders.

Ensembles on the “spring” side of the room included shorts-and jacket combos in traditionally spring-y pastels, marred by everpresent, printed black calf-length socks. Stripped of their arty accessories (spiked leather masks, distressed foam-rubber neck-ruffs, bondage harnesses and melting top hats, some of which were contributed by van Beirendonck’s visual artist collaborators), both collections were surprisingly practical. Where were these outfits when I was agonizing over dozens of thrift store sportcoats for my new “Glasstire Editor” persona?

5 comments

The masks reminded me of a cross between Hanibel Lecter and early slave bondage masks. I was completely creeped out and couldn’t focus on the clothing selection. I do think you would look great in a duo-color blocked suit. Minus the creepy mask

The John Pomara’s exhibition and new works looked amazing, this “review” is too snarky and 1990s jokey.

Bill in the van Beirendonck display:

https://glasstire.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/BillFashion.gif

Rainey, when will Glasstire get an editor for Bill?

I have never seen Bill in a nicer, crisper jacket.