The Program Will Begin Shortly…

Silence is Toby Kamps’ first major exhibition at The Menil Collection since becoming curator of modern and contemporary art two years ago. You should not miss it. It’s been too long since you visited the Chapel anyway.

But silence can be hard to find. We arrive at the Rothko Chapel to hear Jacob Kirkegaard, Steve Roden and Stephen Vitiello perform As If They Were Not There, but there are two of us and with only one seat remaining, I choose solidarity and miss it. But I did hear a comment from a passerby afterwards: “It was just a lot of noise.” Could be ear of the beholder, but this is just a prelude: silence rarely is.

“Without silence the teeter-totter of success will tilt in the bad guy’s favor.”

So says combat veteran Jason Everman, who knows that it is his own breath, heartbeat and nervous system that prove the John Cage statement, “there is no such thing as silence.” Everman, also a musician who briefly played with Soundgarden and Nirvana, is discussed early on in George Prochnik’s book, “In Pursuit of Silence,” a primary text referred to in the Menil exhibition catalog for Silence. Cage experienced his own body as a source of sound in an experimental anechoic chamber at Harvard in 1951. Everman heard the highway inside his veins during moments of total silence in Iraq and Afghanistan, when his survival depended on listening.

And I am looking at Ad Reinhardt’s Abstract Painting (1954–60). It is not black, as people like to say—if anything, it’s purple, but its near-black intrigues. As I draw back for a wider-angle view, I am barely able to hear the tiny saws and hammers at work inside Robert Morris’ 1961 sculpture, Box With The Sound of Its Own Making. Eventually the sounds it contains becomes audible, but just in the nick of time before I walk into it backwards. It is well made from what I hear. But in the stutter-step I employ to avoid the inevitable moment in which painting is differentiated from sculpture, I am like the Cistercian monk described in the Prochnik book who says, “silence is for bumping into yourself.”

And so through the spaces of Silence I continue with the sound of my own continuing.

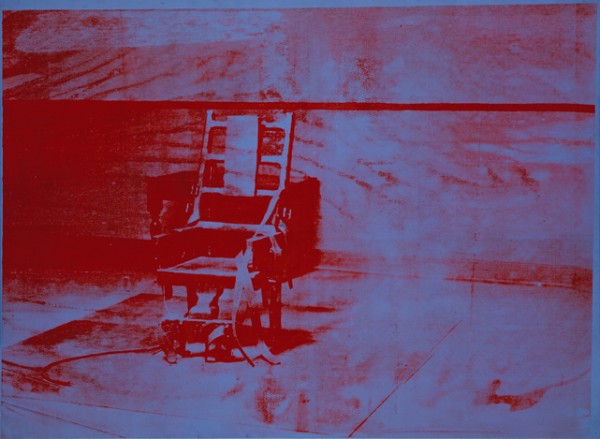

Andy Warhol, “Big Electric Chair,” 1967, © 2012 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. The Menil Collection, Houston, Gift of the artist. Photo: Hickey-Robertson, Houston [No press image available for “Little Electric Chair “(1965)]

There is the room entirely devoted to Christian Marclay’s treatment of Andy Warhol’s electric chair, in which he seizes upon the “SILENCE” sign in the execution room. Taking his cue for license, I’m saying that on the day I am in the museum, a gold lame caul hangs across the thruway, obscuring entrance to his piece, but Marclay’s license/silence plays a good duet with Bruce Nauman’s neon violence/violins/silence, which crackles and buzzes in another section of the show. Warhol’s black-on-black Little Electric Chair (1965), the best piece Andy ever made, is subtle and persistent and holds the room like the comma in “Paint It, Black.”

(center) Bruce Nauman, “Violins Violence Silence,” 1981-1982. Neon tubing with clear glass tubing suspension frame (exhibition copy) Tate and National Galleries of Scotland. Lent by Anthony d’Offay. The Menil Collection, Houston. Photo by Paul Hester.

In Tino Sehgal’s Instead of allowing something to rise up to your face dancing bruce and dan and other things, a dancer slowly shifts position in a large, empty room. For the most part, spectators give her lots of space—after all, she’s writhing on the floor. But this one guy wearing a Jackson Browne t-shirt walks very close to the dancer, admonishing her for making marks on the wall with her feet. I conclude that silent art can provoke unconsciously anxious behavior.

When I return to the museum a couple of weeks later, a male dancer is taking his turn on the floor. He, like the previous performer, wears ordinary clothes. His movements are supple with sudden shifts into stiff and uncomfortably angular relationships with the surface below him. For a time, he is flowing or melting across the floor, almost as if being born, and then he’s arching into a tense posture sprung from the floor, giving the appearance of a discarded toy or other inanimate object. The continually gradual and constant movement is so minutely rendered that it suggests suspended animation, but any movement, regardless of how slowly it unfolds, is still movement—the animation that is suspended is elsewhere, perhaps in your head. These performances create an infectious quietude that verges on silence as a form of stillness.

I am sitting opposite him, on the floor as well, but about 40 feet away. The wall behind the dancer is a forest of footmarks made by the previous dancers. At one point, he has both feet flat on the wall—it deeply affects my perspective—I am above him, the wall beneath his feet becomes the floor of a suddenly elongated room.

Then the dancer is bent 90 degrees at the waist, back against the wall. He allows his torso to slowly fan across the wall and return to the floor on his other side. His left hand is loosely telescoped over his left eye, as he rises and then recedes, periscope-down, silently descending like a submerging submarine.

If photography breaks reality into split seconds that are otherwise imperceptible, then this slow-mo dance connects the missing pieces in a movement so painstaking that it requires the viewer’s sustained attention just to recall the continuity. Pushing the viewer in this way is good, even if most are not up to it.

The four different dancers I witness seem aware of the spectators, either avoiding eye contact or sometimes gazing back. It is impossible to exclude the presence of other viewers as part of the experience being offered. Even the cautious ones are part of the story. Children are transfixed and/or looking at adults for clues. Some who consider venturing into the room linger at the entrance, somehow reluctant to come further.

From my location on the floor, I hear a siren. It is impossible to tell, in this den of silence, if it is passing outside or part of one of the many audio works in the show. I hear, in addition to the siren, clapping, voiceovers, someone singing “Silent Night” and later, a song which includes the words “fricassee infantry,” various tool sounds from Robert Morris’ now louder piece, water running, church bells, a bugle blowing “Reveille,” sounds of sputtering neon, John Lennon singing “Imagine,” an intermittent drone that seems to come from the ceiling, etc.

Drawn into the fray, I float from sound to sound, such as those found in Kurt Mueller’s Cenotaph, a Rock-Ola jukebox collection of “moments of silence” memorializing one thing or another. In this instance it is for the casualties of the 2008 Sichuan/Chengdu earthquake. The silent moment, as Cenotaph makes clear, is never the quiet we imagine. In the earthquake memorial it is filled not with the noise of people being quiet, but with a cascading bray of car horns piling up like an accumulation of bones.

Yes, silence can be hard to find, but it’s easy if you try.

(echo)

One of the most silence-invoking works found in the eight rooms of Silence isn’t even in the show, but hangs on its periphery. Magritte’s The Empire of Light, looking for all the world like a Jackson Browne album cover sans ’53 Chevy, invites stillness in a way equal in reach to the austerity of much conceptual (read: imageless) art. It joins Rothko’s Untitled 1967 in a sort of foyer/decompression area that serves as the anteroom of Slience. And while I am sure it is true that “inside the museums, infinity goes up on trial,” Untitled 1967 is the tiniest Rothko I’ve ever seen. How very 21st century!

Jacob Kirkegaard, “AION,” 2006 Video and sound installation (DVD, 50 minutes) Dimensions variable, format 4:3

Jacob Kirkegaard’s AION captivates for its full 50-minute length. Employing a recording technique similar to those explored in the sixties and seventies by Terry Riley, Pauline Oliveros, Alvin Lucier, Robert Fripp and others, Kirkegaard builds the latent quiet of the bleak spaces of Chernobyl into a beckoning drone. Each of the four spaces abandoned in the wake of the infamous nuclear accident—pool, concert hall, gym, church—is recorded for a set period of time. Then, that recording is played in the same space and re-recorded. The process is repeated again and again, until the minute noises of nothing are built up into a shimmering hum that threatens to summon the ghost of Tarkovsky.

In one section, increasing volume and a slowly zooming camera are coordinated with the falling dark. A busted piano lurks stage right, abutted by a parallelogram of light streaming through a window onto the floor. The myriad hues of light ripple as if molten, eventually shifting and darkening into a pink-tinged black. Just before the black deepens, it burns a shadow on my retina, which lingers like a moth on the finally completely black screen. In another sequence, a digital permafrost gradually covers all the surfaces as the sound gathers. As the white spreads, the black drains.

Steve Roden, “Tacet Permutations,” oil, acrylic on linen 81″x81″ 2012, photo by Robert Wedemeyer, courtesy of Susanne Vielmetter LA Projects

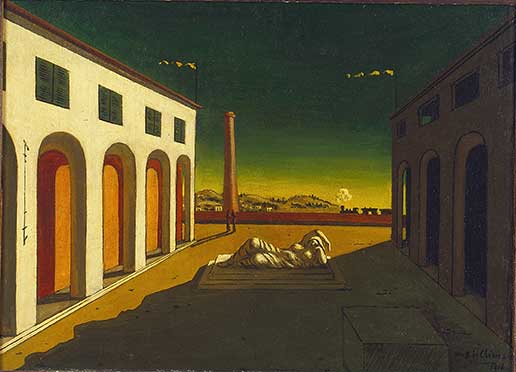

I have a de Chirico moment, because sunlight pours into the room while I am gazing at Steve Roden’s Tacet Permutations. It washes across the wall and the painting as if a time of long shadows is coming. And indeed it has in the De Chirico, the one you’ve seen, Melancholia. It’s back in the adjacent room and it looks like a scene from one (or all) of the songs on “Blood On The Tracks.” There are LPs all over this silent show—Beck-Ola, it’s just right around the corner.

Tacet Permutations seems based on hidden structures that are not consciously known, but in some way apprehended. It invites continuous examination and focused attention. Whatever silence is composed of, I am certain that attention is the way to hear it. Roden’s painting facilitates this activity. Or to put it another way, it is fun to stare at for extended periods of time.

Manon de Boer, Two Times 4’33”

Piano virtuoso Jean-Luc Fafchamps performs Cage’s 4’33” in Manon de Boer’s film Two Times 4’33”. With a face not made for radio, he pretty much conveys the roadmap—where silence lies, where those hidden structures come from—his acts of attention, focus and refocus create in the viewer the same attributes.

The film conceals a great concept—the audience in the scene cannot be heard, even as the performer produces the very piece that is intended to demonstrate how full of sound silence is. The final scene comes as the camera pans beyond piano, performer and audience to telephone wires crossing the landscape, conveying voices unheard, a staff empty of notes. Cut to black. Applause.

The tone, if not the hue, of Silence is set by Rauschenberg’s White Painting. Cage and Duchamp follow suit. All three of them show up looking like Yoko wearing John’s clothes. I carried a copy of Cage’s “A Year From Monday” in 1969. It held these words (or some much like them): “If you don’t know where to start, start anywhere.” Good advice. And good for experiencing Silence, as it is without any sense of beginning or end.

Silence

The Menil Collection

July 27 – October 21, 2012

_________

Lubbock native Hills Snyder lives in San Antonio. He is an artist, curator, song writer and director of Sala Diaz. You are invited to follow his writing on the Facebook page U.S. 87.

2 comments

I am huge fan of this exhibition, and I think it holds up very well to repeated viewings.

For me the most powerful moment is the way Joseph Beuys’ “Das Schweigen” (5 film reels of Bergman’s film of the same name, encased in copper and zinc) interacts with Doris Salcedo’s “Untitled” 2001, (A dresser and wardrobe filled with concrete).

The Marclay/Warhol room is also amazing.

From an email received from George Prochnik, author of In Pursuit of Silence: “I think you’ve done a lovely job, covering a lot of ground very cleanly, suggestively and lucidly — not an easy triad to sustain.”