White Oak Bayou on August 27, 2017 during Hurricane Harvey

[The following is the first in a series of voter awareness articles we will be running this fall in advance of the national elections in November. Your vote matters. Regiser here. – Ed.]

There is a special election scheduled for August 25th, 2018, which all Houstonians should vote on. If you live here, or work here, or have family here — if you have any economic or emotional tie to this city — this election will affect you personally. At stake is a $2.5 billion Harris County flood bond, funded by a 1.4% increase in property taxes, for projects that will occur over the next 15 years. (For a full list of proposed projects, which include buyout areas, repairs and drainage improvements, visit the Harris County Flood Control website.)

We all lived through Hurricane Harvey, and now is your chance to do something about our collective response to future flooding events. We can’t floodproof Houston, but we can be much better at dealing with catastrophic amounts of water falling from the sky or surging in from the ocean. This one bond is not going to solve all our problems. There are still competing ideas about what should be done to address flooding in Houston (and powerful forces aligned behind those ideas). But it’s a start, and your voice should be heard.

If you are curious to hear more about the contents of the bond, you should consider attending a presentation by Bill Fulton, the Director of the Kinder Institute, on Wednesday, August 22, 2018 at 6:30 pm at Congregation Emanu El in Houston.

I spoke this week with Fulton about the bond. “My basic message is that floodproofing Houston involves more than just hard engineering projects. It involves intelligent use of how to conserve land and intelligent use of infrastructure,” Fulton said. “Nobody wants to talk about regulation of land that would take land out of the market, but we have to put all solutions on the table rather than just try to engineer our way out of this.”

White Oak Bayou, then and now: an undated image, top, courtesy of Houstorian.com; and a more recent image of White Oak [via Houston Public Media].

Some ideas you’ve probably heard about are not addressed by this bond. There’s the apocryphal “Third Reservoir” that was discussed so much in the immediate aftermath of Harvey, and whether its purpose should be to protect existing houses, or to protect undeveloped land so that it can be developed in the future (guess which option real estate developers prefer). Also unmentioned by the bond is the so-called “Ike Dike” (based on a similar project in Holland), which petrochemical companies and some Texas politicians desperately want to construct in the ocean along Galveston and Bolivar (guess how environmentalists feel about this). And then there are the rumblings one hears about a rather ludicrous plan to build gigantic tunnels that would somehow collect all the water in Houston and dump it into the Gulf of Mexico. These are the projects I assume Fulton referred to when he spoke of “engineering our way out of this” — ideas that appeal to Texans who are looking for big-ticket, solve-everything projects, rather than facing the difficult reality of flood control at a more granular level.

I asked Fulton if we were thinking big enough with this bond. “I’m worried that we’re not thinking small enough,” he said after a pause. “It’s easy to try to solve the problem with a few big projects. But the problem has to be solved street by street, neighborhood by neighborhood, ditch by ditch. I’m worried we won’t have enough small, distributed solutions. You can make a big difference in a neighborhood with small solutions. But you have to remember that there are millions of neighborhoods.”

An interactive map of proposed bond projects created by the Houston Chronicle.

One of the problems with flood control is that big projects are time-consuming and cumbersome, far more so than transportation projects like highways. It can take a generation or more before a city sees the fruits of flood control investments.

Another problem in Houston is building codes, which everyone agrees must be updated. None of those styrofoam condos that are crammed 8-deep on lots that used to hold a single small house have been required to do anything about water runoff (this is also true of standalone commercial buildings — as long as your local donut shop or dry cleaner was smaller than a certain size, that business could pave over their entire lot and not do a thing about flooding). Larger developments have more recently been required to build retention ponds, but those ponds eventually fill with vegetation if they are not maintained.

But perhaps the biggest flooding issue in Houston — one that nobody in a position of power wants to talk about — is Buffalo Bayou. Something close to one-half of all the watersheds that drain in Harris County eventually flow into Buffalo Bayou, and there is currently no plan for it west of Shepherd Drive. No buyouts, no infrastructure, no parks. Buffalo Bayou is the foremost public asset in our metro area, but from Shepherd west to Beltway 8, it’s off-limits to the public, save for a single entrance for canoes at the West Loop. The Spring and Cypress hike-and-bike trails along their bayous have become fantastic amenities, and ones that prevent vulnerable development close to the water. Even though Buffalo runs through some of the wealthiest neighborhoods in Houston, is it not possible to imagine that we could recreate that success along our biggest bayou?

A Cypress Creek bike trail. [image via the Houston Chronicle]

Sims Bayou (which you drive over on the road to Hobby Airport) is the most recently completed federal flood control project in Houston. Started in 1990, the Sims Bayou project was slated to be yet another unsightly concrete funnel, until local landscape architect Kevin Shanley somehow miraculously convinced Harris County Flood Control and the Army Corps of Engineers to leave the banks green and grassy. A generation later, Sims looks good (no concrete funnels), provides recreational benefits to residents, and — because the project bought out homes along its banks and widened it considerably — can convey a ton more water than it could before. Which meant a lot during Harvey: Sims was one of the only bayous to stay within its banks during Harvey, saving 1,330 homes that had flooded during Tropical Storm Allison in 2011.

Sims Bayou after the flood project [image via SWA Group]

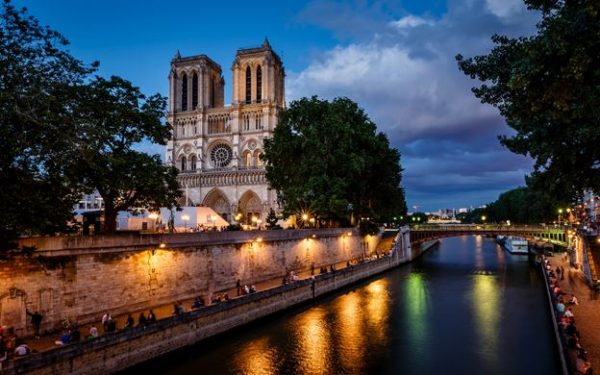

Of course, if you want to really dream, you could imagine downtown Houston looking like Paris with the Seine running through it. We could do that, you know. Some people might not like the loss of green banks, but it would also mean that Buffalo wouldn’t get so badly trashed in the next flood.

Houston is my hometown. I love this city because, for all its ugliness and its terrible summer weather, (and however corny it may sound), Houston is a city that has a palpable sense of freedom and possibility. Thin on history, Houston is a forward-looking city, one that fosters a feeling that you can do whatever the hell you want here. (In some cases, you literally can: we famously have no zoning laws.) This is not to suggest that struggle and sadness don’t exist in Houston; but having a generalized, exuberant sense of possibility makes a city great. It’s great for artists, which is why I stayed here. It’s also great for business — and economic prosperity makes art possible.

Expensive and unnatural, but oh so beautiful: the Seine in Paris

Of course, there is a dark side to being able to do whatever you want. For one thing, Houston only relatively recently started to consider its looks. To make a city look good requires some amount of planning and foresight and — like it or not — centralization of control. Those things are also necessary for effective risk management. Somebody who has a motive other than profit needs to be in charge to make sure the wheels don’t go off in a disaster such as unprecedented, catastrophic rainfall.

There’s an argument that Hurricane Harvey was unstoppable, that there was nothing we could have done to mitigate the scope of the disaster. It’s true that Harvey was going to cause flooding no matter what. But it’s also true that we paid the price for our decades of carelessness in abdicating our responsibility as a city to plan—except in localized instances of successful projects like Sims Bayou.

What we know for sure is that this is going to take time, and it’s going to require imagination, courage, and patience from us as a community. The solution won’t be just one thing or just another: as Fulton said, “we’re going to need to have a both-and solution, not an either-or solution.”

Step one is for all of us to take a moment and study up on this upcoming Harris County flood bond election. (Again, it’s scheduled for Saturday August 25th, 2018. Find your polling location here.)

Your vote matters.

1 comment

thanks for writing this, Houston has potential, tons of it