The Galveston Artist Residency (GAR) may be the best artist-in-residence program in Texas. At 11 months long, the program gives three artists studios, lodging, a $1000 monthly stipend, and, because it’s Galveston, a bicycle. There’s not much to do on the sleepy island; after you visit its historic houses, the Bryan Museum, and the ocean, you’re left wondering what’s next, and if you’ve looked at one shell shop, you’ve more or less seen them all. The town, then, offers what some artists dream about: an unfettered opportunity to bear down and focus on their work.

Every spring, GAR puts on an artist-in-residence exhibition, showing the disparate artwork of the three strangers that lived and worked in the same building. There’s usually not much of a connection between the three artists’ work, but in its sixth iteration, this year’s residency show is different. The combined works of the three artists — Leonardo Benzant, Fidencio Fifield-Perez, and Pat Palermo — cohere, and share a sense of urgency that I haven’t felt this strongly in past GAR exhibitions. One reason for this is that these artists are reacting to their environment, to the political moment — all three residents began their stay in the summer of 2016 and then, along with the rest of us, went through the life-changing 2016 election. For three artists so deeply tapped into the cultural consciousness to collectively experience an event as monumental as the election of Donald Trump, bonding and the sharing of a common sense of urgency seems inevitable.

One reason this sensibility echoes so strongly throughout the show is because Fidencio Fifield-Perez is an undocumented immigrant. Brought to the US at the age of seven, he was the first member of his family to graduate high school, and because of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, he was allowed to legally work in the country. He has three degrees, has taught college courses, and now, is frightened over whether or not he will be deported. In his profile, submitted to the New York Times’ American Dreamers opinion page, Fifield-Perez writes: “Are these words enough for you to acknowledge my existence or my humanity?”

This sentiment finds its way into Fifield-Perez’s work. In some pieces, layered found maps are cut into chain-link fence patterns and splattered with acrylic and ink, turning an object we associate with travel and accessibility into a barrier preventing us from arriving at our destination. Other pieces are more intimate and subtle, like paintings of cacti and succulents the artist has executed in acrylic on used envelopes, obscuring the name of the recipient (presumably the artist) in an effort to hide communications and make private a life that has become a subject of public discourse. And the most poetic work is his wood planter filled with cacti, that on the surface look normal, but on close inspection appear to have their natural spikes augmented and bolstered with painted toothpicks — a gesture jabbing at the way some perceive both our border and those who cross it.

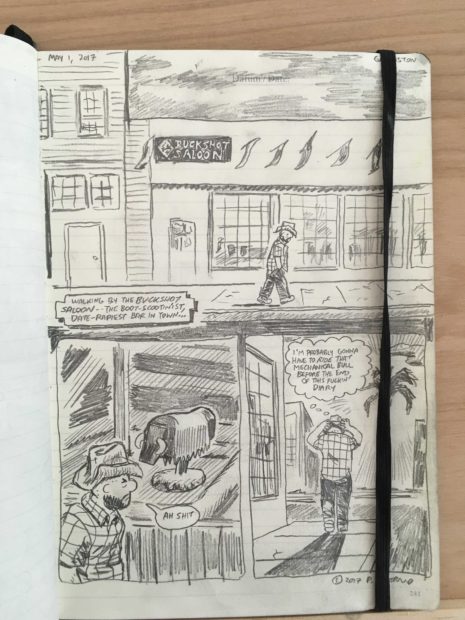

Some of these issues also pop up in Pat Palermo’s comics that he made during his time in Galveston. An illustrator at heart, Palermo’s specialty is in turning the banal, humdrum moments of our day-to-day lives into biting social commentary. His output at the residency was prolific. In an effort that simultaneously gave him instant content and demystified what artists do with their abundance of time at a residency program, Palermo created a daily comic about things that were on his mind — dreams from the night before, thoughts about Houston’s Rothko Chapel, his problems voting in Texas with a New York ID, and issues surrounding his fellow residents. The best of these vignettes were re-drawn, inked, and turned into zines you can buy from the GAC. After reading the three volumes available, covering September through May (the last volume will come out this fall), I felt like I intimately knew the three artists in the exhibition. The daily diary offers everything from Palermo’s vapid musings, to Galveston mini-history lessons, to painful conversations the residents had about the state of our society. Palermo’s storytelling strength is in his ability to condense events and conversations down to their bare bones while still capturing their heart. Most of the anecdotal events fit on a single page.

Palermo also gives us the rare chance to witness, in real time, the culture shock of a New Yorker coming to Texas. In the sleepy coastal town, everything moves at a snail’s pace compared to the hustle of NYC. But it’s nice to see that even Galveston offers the artist formative experiences — he attends his first drag show, encounters local legends, and resigns himself to the idea that he may ride a mechanical bull before he gets off the island.

The last resident, Leonardo Benzant, used his time in Galveston to expand his thinking about ancestry. Drawing on his Afro-Caribbean heritage, Benzant creates large-scale wall collages that look and feel like two-dimensional versions of Nick Cave’s costumes. Towering over the viewer, the colorful textured pieces are abstract but hint at figuration. The spiritual titles of the works, like Simbi Kia Masa (Spirit of the Water): One, imply that some of the collages don’t depict beings, but instead, capture an essence. In prior artist statements, Benzant has said he thinks of the artist as an “Urban Shaman” whose job is to “bridge the visible and the invisible worlds.” All of his pieces have a mysticism about them that asks to be tapped into and accessed by the viewer, and in an age where everything is over-explained and codified, it can be nice to encounter objects where their feel is prioritized over their hard-and-fast meaning.

When you accept three strangers into a residency, you roll the dice: personalities can be combative, artworks can work against each other, and the general spirit of a program can tip depending on slight interactions. The three artists chosen for this year’s GAR residency aren’t alike, but the show works like a curated group exhibition. If you have three people whose job it is to think about the world we live in and communicate something crucial about it, it’s not surprising that, right now, they may end up on the same page.

1 comment

There’s a Bryan Museum?