For American artists of my generation, born well into the 1970s, the Cuban Revolution depicted in the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston’s Adios Utopia: Dreams and Deceptions in Cuban Art Since 1950 is an abstraction. For those of us born into the lower-middle class and poorly educated in the suburban public schools of the ’80s and early ‘90s, the very idea of a revolution elicited either a low Butt-head chuckle or a manic Beavis laugh. For us clerks and mallrats, Francis Fukuyama’s pleasantly anti-historical notion that the whole world was one long wagon train on the dusty trail toward liberal democracy, with settlers at different stages of historical development along the way, seemed terrible.

If Fukuyama was right, then our lives of chain-store family dining, VHS porn and dirty ecstasy tabs were, if not the very tip of the liberal utopian spear, at least somewhere in the vicinity of the arrowhead. We were the most privileged teenagers in the entire history of teenagers. We were also the first generation to watch our parents abandon each other en masse through divorce. Too busy getting rich or just keeping afloat, our parental units gave us the keys to an empty house and had the gall to call us latchkey kids. Our parents were the ‘60s and they were obviously not to be trusted. This, at least, is how it looked from the spiritual ghettos of suburbia in 1994. We were the most cynical generation of Americans in the country’s 200-year history.

In order to get a grip on the animating forces behind Fidel Castro’s revolution, and the art produced by and in response to it in Adiós Utopia, I have to travel back in time to my father’s generation. In the 1960s the idea of a socialist utopia seeped into virtually every culture and subculture. I was born in Arizona where my parents had moved to join a fundamentalist church and wait for the end of the world. It was in this environment that I came to understand that socialist utopias exist on the left and on the right. What I also learned was that self-interest, deception and oppression reign in religion, socialism and any other ideology that takes on a utopian bent.

In his memoir, Hitch 22, the journalist Christopher Hitchens, born in 1949—the same year as my father—writes about being a fresh-faced 18 year-old member of the International Socialists and visiting Cuba in 1967. Eight years after Fidel Castro had assumed dictatorial leadership of the small, sugar-producing island, Hitchens and a small band of Oxford-educated Marxist idealists wanted to witness first-hand the promise of this new society and its charismatic leader.

Hitchens sums up the life of the artist in revolutionary Cuba with a passage in which he describes putting his foot in his revolutionary mouth during a Q&A with the famed Cuban film director Santiago Álvarez. After an outdoor screening of Álvarez’s film LBJ (which stood for Luther, Bobby and Jack), in which Álvarez claimed that Lyndon Johnson personally ordered the assassinations of John Kennedy, Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy, Hitchens asked Álvarez how he found it, “as an artist, to be working in Cuba, a state that had official policies on the aesthetic.” Álvarez replied that his freedoms were “untrammeled.” Pressing him, Hitchens inquired if there were any exceptions to this unbounded freedom. Álvarez replied that obviously it would not be “possible or desirable to attempt any attacks or satires on the Leader of the Revolution himself.” And there you have it.

Navigating a historical exhibition like Adiós Utopia can be difficult. The museum’s didactics do a reasonable job of providing a broad outline, but even this is little help in finding a personal position from which to steer your experience. In order to make sense of large-scale historical exhibitions, most viewers need to be able to recognize themselves in specific works. This recognition opens a personal wormhole through which the other work in the show can come into sharper focus.

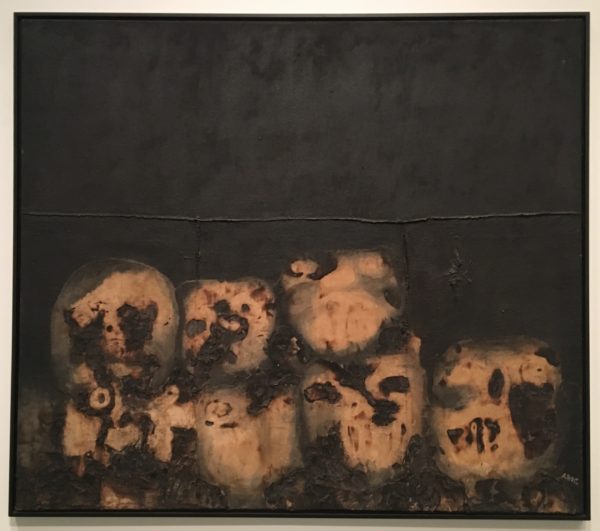

For me, Antonia Eiriz’s large oil paintings are the dark heart of the Cuban Revolution, and a key to the rest of the show. In big square canvases that might easily be the album art for Nine Inch Nails’ angst-saturated 1994 record The Downward Spiral, Eiriz drags Goya, deaf and blind, onto the stage of the revolutionary ‘60s to witness, all over again, the disasters of war. Speaking across half a century, she shows that every revolution, whether conservative or progressive, feeds on an unquenchable thirst for revenge. A heart needs blood to beat.

In The Privileged and the Underdogs, the members of both “classes” howl at the artist in her studio through a window and a propaganda machine that might once have been a television. On an easel, behind another Cronenbergian machine that seems to have devoured a phonograph, the violent, stupid creatures that hector Eiriz from inside the screen and outside her window also torment her from the surface of her canvas.

In The Procession, Eiriz’s dank black abstraction evokes nothing so much as the severed heads and stacked skulls that will always be found fertilizing the killing fields of wars and revolutions. Indeed, she seems to ask if there is a difference between the two. Created in 1963, Eiriz’s grim, expertly painted canvases reveal the early stain of corruption and horror in Castro’s political executions, forced labor camps and artistic censorship. But Eiriz also tells us something deeper. The pain of the Cuban people, aggrieved and punished by the totalitarian tyranny of the U.S.-backed dictator Fulgencio Batista, brings forth a tyranny of its own. The cry of “to the wall, to the firing squad” that accompanied public support for Castro’s political executions, echoes out from Eiriz’s paintings more than 50 years later.

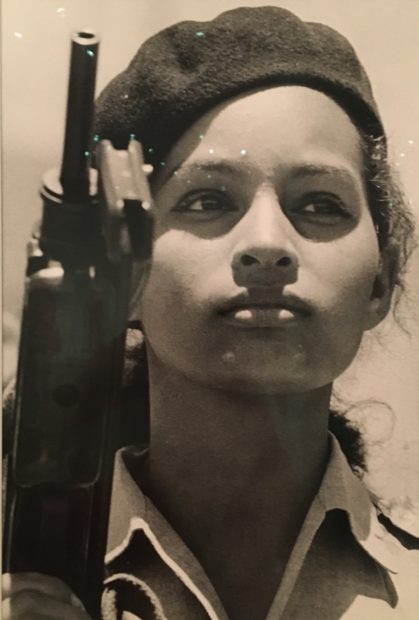

Leaving the gallery in which Eiriz’s paintings are hung, I stopped to look at a series of black and white documentary photographs of the first happy moments in 1959, when U.S. backing for Batista was withdrawn and the revolutionary government had taken power. Scanning images of peasant cavalries in the street and voluptuous women wrapped in the Cuban flag, my eyes settled on the stoic but angelic face of young girl holding an automatic rifle. Hung a few feet from Eiriz’s bleak account of those early days, Raúl Corrales’ young girl in The Dream forced me to wonder exactly when it is that justice becomes bloodlust.

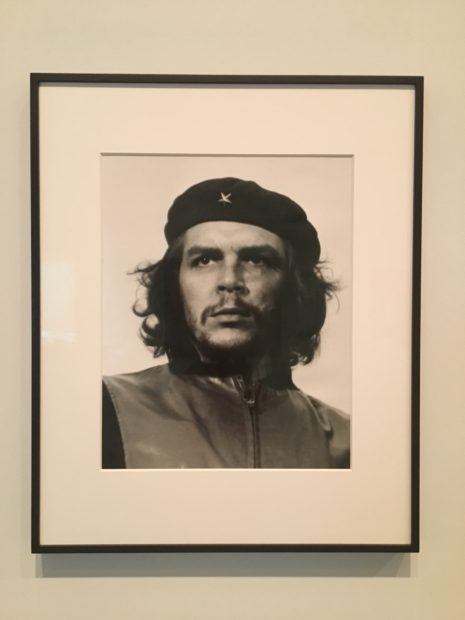

No exhibition of images produced by the Cuban Revolution would be complete without the most iconic image of the entire early era: that portrait of Che Guevara. Stern, unwavering, and unquestionably sexy with his long hair blowing in the wind, Alberto Korda’s, Heroic Warrior—cropped from the original image that depicted Guevara on a platform surrounded by a crowd— has been silkscreened onto the chests of millions of bourgeois rebels all over the world. But, apart from this iconic image, which somehow still retains a shred of power after its full and complete cooptation by capitalism, who was Che?

The unavoidable comparison of Korda’s iconic image to Jesus Christ himself is not exactly a dishonest one. Ernesto Guevara, born into an Irish-Spanish family of the name Lynch, traveled the countryside of Latin America by motorcycle during his early medical studies to become a doctor. His memoir, The Motorcycle Diaries, gives a kind of counterculture account of his travels and aligns him as a writer both by period and in tone to the Beats in the United States. Like Christ before him, Guevara ministered to lepers while meeting real-deal socialist doctors in the field, before he became the director of the Cuban National Bank and signed the ten and twenty peso notes “Che” (which roughly translates to copain, or friend). From lepers to banks, in Che we trust.

After extensive travels and studies of his own, Guevara, then working as a journalist, fell in with the Cuban cause (after Castro’s failed attempt in 1956 to launch a revolutionary attack) by traveling from Mexico—where Castro had fled after a brief imprisonment for a failed attack on a military barracks—to Cuba by boat. Run aground, the survivors fled into the Sierra Maestra mountains where they spent the next three years strategizing. In many ways Guevara remained the idealistic, but also rigidly doctrinaire, heart of the revolution. Even after Castro had begun to settle into his role as emperor, Guevara helped train many revolutionary socialist insurgencies including an early incarnation of the Sandinistas.

But his appeal to teenagers everywhere might best be seen during an interview with three pudgy heads on Face the Nation in 1964. The interview is set up in the form of a tribunal, with Guevara at one end of a room and the three interviewers at the other. His eyes never stop laughing and he smiles constantly at the hypocrisy of this trial-by-interview conducted by the representatives of a nation that had supported a regime whose oppression had played a huge role in summoning the revolutionary forces to begin with. When asked what conditions the Cuban government was willing to meet in order to normalize U.S. relations, Guevara, hair cut and combed back like James Dean or Dean Moriarty, asks why Cuba should meet any conditions when they do not demand, for example, that the Americans end racial discrimination.

Alberto Korda, Camilo desfila con la caballeria (Camilo Parades with the Cavalry), 1959, gelatin silver print

In 1967, not yet 40 years old, Guevara was captured and murdered in Bolivia by the local, U.S.-supported military. As he had in the early days of the Castro regime, he had continued to work to create not just a socialist Cuba but a socialist southern hemisphere. What the hard, unquestionably committed but ultimately brutal and unforgiving life of Guevara teaches us is that, no matter how damned a revolution is at its inception, or may eventually become, it will never take place without figures willing to kill and die for a cause. But in case we find ourselves swept away by the romance of Guevara’s charisma and early death, we should remember the screams coming from Antonia Eiriz’s black paintings. It was Guevara who enforced Castro’s sham trials and brutal executions.

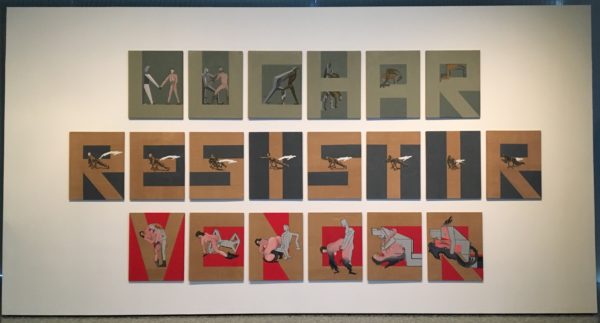

Adios Utopia boasts more work in painting, sculpture, photography and video than can reasonably be accounted for in one review, but the painting installation Fight, Resist, Win by Carlos Rodriguez Cárdenas returns me to my own bleak generation. Born in 1973, Cárdenas is three years my senior and his darkly comic paintings seem to prove that the dead-end irony of Generation X knows no borders or walls. Twenty medium size canvases, arranged in three rows, spell out the words, LUCHAR, RESISTIR, VENCER. Each canvas accounts for a single letter. The letters are animated by hapless humanoid figures who fight against angular robots within the geometric confines of their runes.

In the line that spells LUCHAR, a faceless, sexless humanoid shakes hands with a robot in the airy space of a big “L.” But that’s the last gesture of friendship in that line. By the time we reach the “R,” the person has fused with the robot and become imprisoned in the small rectangular cut out of the capital letter. Fighting power, it seems, will find you in a prison cell.

In the line below, what appears to be a male figure in revolutionary uniform bends over a stool as a digitized white cloud burrows its way further and further up his ass. By the time we reach the ‘R” in this line the figure appears to be boiling while the “the cloud” which we’re told will liberate us, remains embedded in his ass. Resist? How? They’re everywhere.

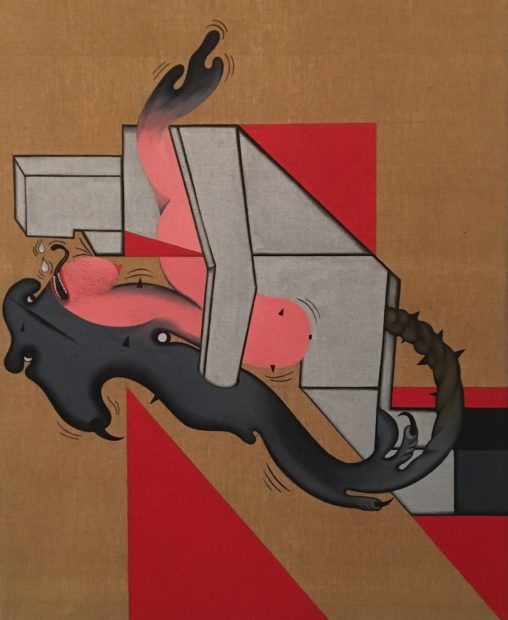

Finally a very pink woman, who looks more like an inflatable sex doll than a human being, starts out her phonetic dance backed up on a silver robot dick. In the next panel, she rides him reverse cowgirl. But as the creature stands up and begins to take more control over their cartoon copulation, she begins to mutate, with inky blackness rising up from her arms and feet. By the time we find ourselves once again at that damned “R,” she and he (or it) are one. How can we win? Well, as the old saying goes: If you can’t beat ‘em, join’em.

Adiós utopia.

3 comments

The “digitized white cloud” in the Resistar portion of the Carlos Rodriguez Cárdenas tritych is actually the island of Cuba itself.

Thank you for an excellent article on this show–which I especially appreciate because I probably won’t have the chance to see it in person (I’m reading this in Oregon ^_^). Even though I’m fond of propaganda posters and murals, I try to at least bear in mind that I’ve never personally had to live under authoritarian regimes of the kind that produce them, unlike artists such as Cárdenas and Eiriz. Ironically, I therefore have the freedom to view such propaganda as art–it’s perhaps a bit like Malraux’s remark that Buddha figures or portraits of the Virgin Mary, crafted as objects of religious devotion, became classed as art when no longer viewed for their original purpose.

Without diminishing the graphic and design value of propaganda, or its iconic power–works which may have, in the end, influenced more human beings than much of the art hung in galleries has–some of the works in this exhibit nevertheless show up the limitations of propaganda versus art. If art has a limited ability to change reality, likewise propaganda has a limited ability to mold it.

Regarding Beavis and Butt-Head, I’m not sure Che could have recruited them to the cause, but perhaps Tania might have. “Whoa! That chick, like…talked to us, uh-huh-huh. Uhhhh…like, venceremos, baby.” “Yeah! Yeah! Burritos! Socialismo o muerte burritos!! Hee-hee-hee!”

Best show is TX as of today