San Antonio-based artist Cathy Cunningham-Little has succeeded over the past 25 years as both an artist and an entrepreneur. Since 1983, Cunningham-Little has run Cunningham Glass Studios, specializing in commissioned glass, neon, and related products. Since 1989, she has been exhibiting her sculptures and installations using mostly glass and lighting materials. In 2005, she combined her expertise in both fields by assisting in the implementation of Teresita Fernández’s permanent outdoor installation in San Antonio’s Chris Park, which serves as the current grounds for the Linda Pace Foundation’s SPACE gallery. Trained at several institutions, including Pilchuck Glass School, the Penland School of Crafts, the Southwest School of Art, and the University of Texas at San Antonio, Cunningham-Little has studied and mastered the technical aspects of her art while also being exposed to significant issues in contemporary art. While her earliest artworks address socially relevant topics, her recent work is focused on questions about perception and aimed at increasing the participatory role of the viewer.

Left: Nebezpeci, 1990, neon, fused and slumped glass, plate glass, wood, 66 x 22 x 18 in. Right: House of Deceit, 1994, lamp-worked borosilicate, 12 x 12 x 8 in.

Much like the younger artist Jennifer Ling Datchuk, Cunningham-Little began her career working in a traditional craft medium, but veered far afield from that medium’s original functional purpose to pursue serious and challenging content. Cunningham-Little’s sculptures of the early 1990s are literally glass houses, each of which has been transformed into a container for metaphoric imagery about domestic violence. The abuse of women was a prevalent theme among feminist artists working in the 1980s (works by Ida Applebroog, Sue Coe, and Nancy Grossman come to mind), and Cunningham-Little handled the subject with considerable finesse and poignancy. In Nebezpeci (1990), the glass house is the receptacle for neon tubing coiled to resemble a cyclone, with the word ‘nebezpeci‘ (‘danger’ in Czechoslovakian, the native language of the artist’s first husband) painted on the glass surface in red paint that drips from the letters like blood. For House of Deceit (1994), Cunningham-Little filled the glass-house interior with borosilicate glass rods, which can be bent and shaped with a torch, a process that the artist compares to knitting or crocheting. Tightly packed within its container, the dense web of entangled borosilicate rods becomes an effective metaphor for the typical network of lies and deceptions that abound in unhealthy relationships.

Around the same time that the Chilean artist Ivan Navarro began making electric chairs out of fluorescent lights, Cunningham-Little had a similar idea and built an electric chair out of pink neon tubing, independent of Navarro and predating his Pink Electric Chair (2006, Collection of San Antonio Museum of Art). Cunningham-Little’s electric chair is one of several components from her installation The Last Meal, which was exhibited in 2004 at the Art Alliance Center at Clear Lake, Nassau Bay, Texas. Inspired as a commentary on capital punishment after reading about “Old Sparky,” the Texas electric chair that executed 361 inmates while in use from 1924-64, the installation takes the form of a domestic setting in which the pink neon chair occupies the role of a lounge chair placed between a family portrait and a TV tray table. The “portrait” is in actuality an image of the electric chair that was burned on to a Transbestos III surface using hot neon tubing (leaving visible scorch marks), and mounted in a backlit gilded frame. On the TV table, Cunningham-Little etched a prisoner’s last meal request that she discovered in her research (additionally intriguing because the list was quite gluttonous and included Rolaids to be taken between the meal and execution). To bring a memorial context and tone to the installation, the artist adorned the other usable wall with glass plates onto which she had etched the names of inmates executed by Old Sparky, along with the dates of their executions.

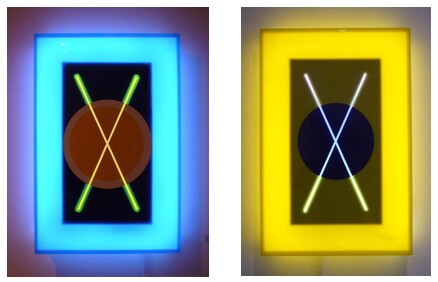

Left: X-Dot Blue, 2007, neon, cut acrylic, vinyl, 30 x 20 x 6 in. Right: X-Dot Yellow, 2007, neon, cut acrylic, vinyl, 30 x 20 x 6 in.

Around 2006, Cunningham-Little shifted her attention from addressing social issues to concentrating exclusively to issues of perception. She attributes this move in part to the fact that her father had lost his vision in 1994 due to a genetic disorder and his descriptions of what he saw purely with his mind got her thinking about how people perceive things. For her 2011 exhibition “Breathing Light,” held at Blue Star Contemporary Art Museum, Cunningham-Little created a series of colorful light boxes using a variety of filter foils, cut and layered to create different shapes. Like Josef Albers, who employed a repeating format of concentric squares to probe variances in color perception in his Homage to the Square paintings, Cunningham-Little set up a similar visual dialogue using a constant compositional template while altering the colors in each instance. Working with light and technology, in fact, allowed Cunningham-Little to carry the investigation further: the size of the imagery of the backlit neon light boxes enlarged or diminished depending on the viewing distance.

Left: Mirage, 2008, neon, nylon threads, 10 x 6 ft. diameter Right: Sweep, 2010, light and sound installation: phosphorescent cotton thread, stainless steel recording wire (Verdi’s “Don Carlos” recording), 10 x 15 x 25 ft.

Moving on from wall-mounted works, Cunningham-Little next turned to making room-scale installations in which thin and barely visible materials are activated by light and change as a viewer moves through a space. For the studio installation Mirage (2008), she constructed a three-dimensional sculpture using nylon threads that are extended from floor to ceiling and tied to and illuminated by circular neon tubing. In the subsequent installation Sweep, exhibited in 2011 at the recently closed Cactus Bra Space in San Antonio, the artist switched from nylon to recording wire, which is more reflective and thus has a greater presence during the daytime. Recording wire is a cultural artifact with a fascinating history, as it was commonly used in the 1940s to capture voices of executives dictating letters or choruses singing acapella. Having acquired a tin of recording wire with an acapella version of Verdi’s “Don Carlos,” Cunningham-Little conceived the idea of creating a light and sound installation where a contemporary variation of the recording embedded in the wires would play in the installation space. After obtaining a CD of the original recording, Cunningham-Little collaborated with San Antonio sound artist Justin Boyd to produce such a score for Sweep.

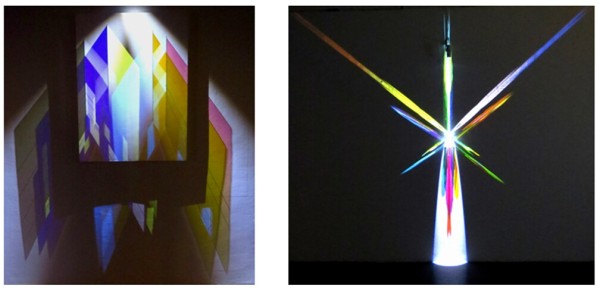

Left: Architectural Tectonic I, 2015, glass, wood, white LED, 90 x 73 x 2 in. Right: JuJu Bwana, 2014, glass, stainless steel, white LED, 144 x 172 x 7 in.

Over the past few years, Cunningham-Little has experimented with ways to form dynamic compositions composed entirely of colored light. With the aid of dichroic glass, which is coated with vaporized metals, she has developed a unique system for creating ephemeral light works, a number of which are currently on view in Blue Star Contemporary Art Museum’s “Back from Berlin” exhibition, which also features works by three other artists (Ricky Armendariz, Karen Mahaffy, and Vincent Valdez) who recently completed residencies in Berlin. Cunningham-Little’s system involves directing light from above towards carefully positioned wall mounted wedges of the dichroic glass, which transmits one color while reflecting its complementary. By adjusting the angles of the glass, the artist is able to manipulate color and composition, attaining results that are quite dazzling. Architectural Tektonic I (2015) was inspired by a visit to the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church in Berlin, which was almost destroyed in a 1943 bombing. With its bold colors and sharp angular planes, this work has affinities with early modern abstraction, such as Frantisek Kupka’s “Vertical Planes” paintings which abstracted the effects of light filtering through cathedral windows. JuJu Bwana (2014) is metaphorically open-ended and can stimulate a viewer’s memories and imagination. Although Cunningham-Little was reminded of an African headdress and thus named the work after the Swahili phrase popularized through Tarzan movies, the spotlight on the floor suggests the lighting of a cabaret stage or the caricature of theatrical lighting that often appeared in Looney Tunes animations.

Cathy Cunningham-Little’s work is on display at Blue Star Contemporary Art Museum, San Antonio, through May 10.

11 comments

Join the MUD underground.

Artists hell bent on taking over the world.

The MUD underground originated in 1976 on the San Antonio River by a group of artists gathered in secret in the abandoned Borglum Studio. (The historic studio of Gutzon Borglum where Gutzon created the model for Mount Rushmore.) The MUD underground is now a international movement. And with the things the way they are, I suggest you join the MUD underground too.

The MUD underground: Where the demarcation lines between politics, religion, espionage, high finance, nudity, and ART begin to dissolve.

“The great artist of tomorrow will go underground” —- Marcel Duchamp Symposium at Philadelphia Museum College of Art, March 1961

Thanks to David Rubin for all his wonderful articles on San Antonio artists.

David, you provided me with an excellent background to Kathy’s work. Her pieces at Blue Star, Back from Berlin, are stunning!

Again beautiful written!

i love the progression of growth with the times to mirror reality

I am intrigued by the Cathy’s evolution in her exploration and use of a variety of unique materials. The design and placement of the dichroic glass and the treatment of the illumination is truly effective.

Very enriching, to read of the evolution of Cunningham’s work over time and in response to different art movements. Thank you, David!

Excellent article, extraordinary artist!

I am extremely blessed to have Cathy as my sister in law and (most importantly) a true friend. She is a great inspiration. We, my wife and I have one of her pieces in our home. “Green Flash”. It is next to my piano and is a constant source of inspiration to help me in my compositions. Thanks Cathy!!

Cathy’s openness and willingness to experiment, grow, and push her work into uncharted territories is brave and exciting. I am always happy with the “now” and always looking forward to the next step.

Thanks to David for writing about Cathy. I have known her for a while but was not familiar with her past works.

I find perception fascinating. I have had small arguments over what is blue and what is teal.Some persons genetically have more color receptors then others. Color is only reflection after all.

Interesting article about the artist, Cathy Cunningham, that uses neon light.

What is next for David Rubin?

Nam June Paik has some interesting work using light and neon. I think it was done in the 1960’s.

Art history speaks volumes about Nam’s work.