“I’m completely against the idea that we do fashion for an elite…That would be too easy, in a way.” -Miuccia Prada

In his State of the Union address on January 4, 1965, Lyndon Johnson said that, “For over three centuries the beauty of America has sustained our spirit and has enlarged our vision…” While Johnson’s statement refers to Americana, his attitude reflects a Romantic position in which spirit, nationalism and landscape are conflated. Often cited as the pioneers of Romanticism in American visual culture, the Hudson River School was immensely influenced by German Romantic landscape painters; both groups shared the perspective that ‘nature’ was a manifestation of the Spiritual, depicting a pastoral setting where humans and landscape coexist harmoniously.* The core sentiments of Romanticism are present in the concepts of beauty and landscape underlying Johnson’s 1965 Highway Beautification Act.

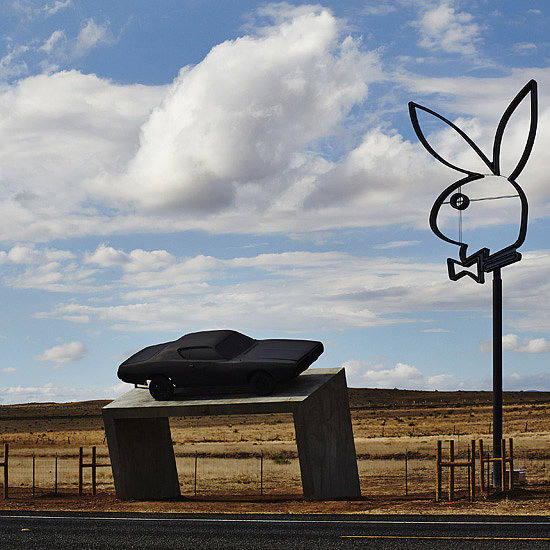

Richard Phillips, Playboy Marfa

Now, the 1965 Highway Beautification Act is being cited to scrutinize both Playboy Marfa and Prada Marfa, aiming to shut both down. While Donald Judd might never have shared such positions, much of the rhetoric referring to Marfa and the Texas desert employs a Romanticized attitude toward the landscape of the American West and the archetype of the frontier man.

This begs many questions which remain controversial. The most recent debates in America surrounding the term “beauty” were resuscitated in the 1990s in several polemic essays by Dave Hickey.

“The beautiful is a social construction. It’s a set of ambient community standards as to what constitutes an appropriate visual configuration. It’s what we’re supposed to like. Beauty is what we like, whether we should or not, what we respond to involuntarily.” –Dave Hickey

In response to Hickey’s premises, Arthur Danto wrote a countering essay titled “The Abuse of Beauty,” which states:

“beauty’s place is not in the definition or—to use a somewhat discredited term—the essence of art, […]That was never its point, nor was beauty the point of most of the world’s great art. It is very rarely the point of art today.”

Hickey’s rationale for “beauty” is as tenuous as Lyndon Johnson’s. Will Prada Marfa become collateral damage in the effort to keep federal highways “beautiful”? Far off in the remote Texas desert, Prada Marfa is the edifice of an international brand glorifying luxurious tastes, an intentional parallel to the Chinati Foundation. It does not seem lost on Elmgreen and Dragset that their career as an artist team also falls into this luxury nexus. Michael Elmgreen’s statement that, “It was meant as a critique of the luxury goods industry, to put a shop in the middle of the desert,” can be understood as an inside joke within the art industry; it is self-parody. When does institutional critique become institutional fetish?

Elmgreen/Dragset, Prada Marfa

Only a spokesperson for the corporation could deny that Playboy Enterprises has attempted to piggyback the situation developed by Elmgreen and Dragset’s Prada Marfa:

“The muscle car hints at a foregone time of luxury, and the similarity between this installation’s concrete form and Judd’s famous field of concrete sculptures is intentional.”

Some might argue that Playboy Marfa’s line of attack is a coup d’etat of American middle class tastes over the elitist domination of European artists and New York minimalism: riffing on the Elmgreen/Dragset discourse of luxury while simultaneously equalizing the status of a Donald Judd sculpture with that of a Dodge Charger and a Playboy bunny logo. Elmgreen and Dragset work with an inside joke that rests upon references to minimalist style and the anecdote of Donald Judd’s retreat to Marfa. Playboy Marfa is subordinate to Prada Marfa and, in turn, Prada Marfa is subordinate to Donald Judd (the Chinati Foundation). I find that this riffing of inside art-world jokes leaves little but diminishing returns. This is not to art what “The Aristocrats” is to comedy.

Following this logic of subordination of Playboy Marfa, it is difficult to see anything other than cynical corporate self-aggrandizement. When Prada Marfa was initially inaugurated, it seemed self-evident that this would lead to a situation like we find today: johnny-come-lately corporate giant seizes upon the precedent and employs it to culturally legitimize advertising.

Only the naïve did not see this coming.

“Art editors and critics—people like me—have become a courtier class. All we do is wander around the palace and advise very rich people.” -Dave Hickey

* “nature”, “beauty”, and “beautiful” are intentionally in quotation marks as they are, to this author, precarious concepts.

1 comment

True. On the subject of beauty and the Dave Hickey/Arthur Danto propositions I think the Glasstire `Suspicious Utopias: An Interview with Matthew Collings and Emma Biggs` makes some innovative advances -particularly in the comments following. As do the editorials/comments about Femen and Pussy Riot art in the Feminist Times (online)