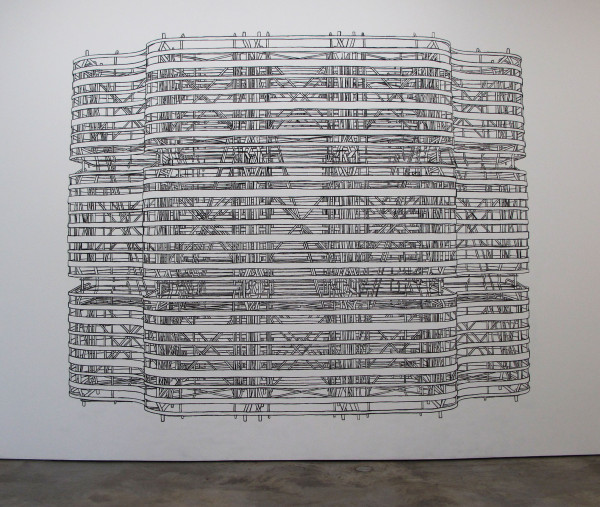

Pablo Siquier’s current installation in Houston is minimal: one wall drawing and an enormous cage-like sculpture fill Sicardi’s lofty main gallery. Three large framed drawings hang in peripheral hallways and stairwells.

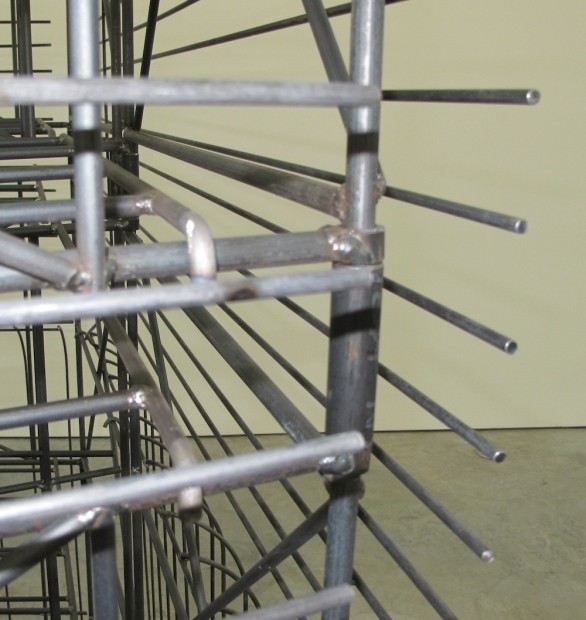

All of Siquier’s works revel in layered, intersecting lines that create Tron-like visions of vast, hypercomplex building-like objects. All are humanized through handicraft: to create his drawings, Siquier traces over computer-generated graphics in charcoal, rendering “artistic” the computer’s impersonal precision. His sculpture’s steel rods are not too neatly welded.

1308

Despite its size and cage-like associations, Siquier’s sculptural contraption, titled 1308 because it was Siquier’s eighth piece for 2013, is as matter-of-fact as its title. Carefully made, but not fussy, its delicacy prevents it from being more than slightly menacing. Unfinished steel rods are welded matter-of-factly, their cut ends slightly beveled to remove burrs that might catch skin or clothing. Emotionally, the effect is deadpan minimalism akin to Judd’s concrete boxes out in Marfa. Were it not so large and so complicated, you’d call it utilitarian, perhaps an elaborate plant stand, turnstile, or newspaper rack. The whole piece is conveniently portable: 16 collapsible units stacked in four columns fold flat for easy shipping.

1301

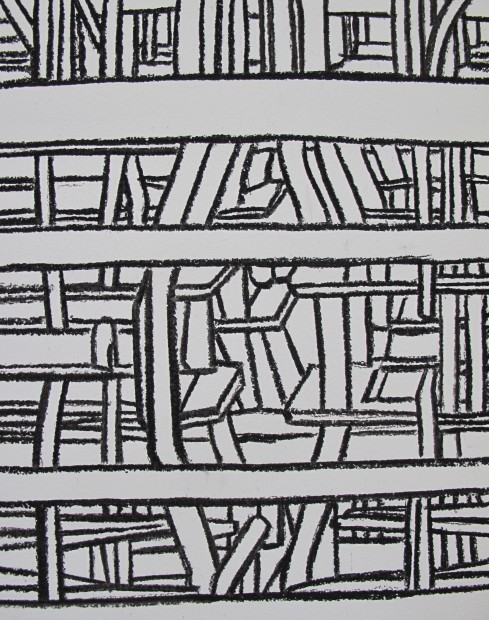

The wall drawing, 1301, is similarly workmanlike, executed in dense, black compressed charcoal over the roller-texture orange peel bumps of the painted walls. Like 1308, it’s large, complex, and executed without mistakes or flamboyant gesture. About nine feet tall, the piece is like a sadistic perspective drawing assignment—levels, stanchions and structures stack, crisscross and interweave in a completely consistent pictorial space until, receding into the distance, they clot into incomprehensibly dense thickets.

1301 (detail)

Like log cabin quilts, or sudoku puzzles, or the obsessively striped paintings of Houston painter Susie Rosmarin, Siquier’s process requires hours of repetitive, intricate, calming work, absorbing care and attention and giving in return a sense of quiet accomplishment that transfers to viewers who appreciate the effort behind the works.

I didn’t ask whether the Argentine artist had drawn it himself or hired locals because it doesn’t matter. Like the steel fabrication for 1308, the drawings’ detached, work-for-hire sensibility perfectly matches its impersonal subject matter. Notably humble, despite their busy magnificence, the works are designed to be executed anywhere—with care, but without passion—like the ubiquitous, technological society on which they comment.

After a brief first impression of a grand order, both the sculpture and the drawings beg for deconstruction, stimulating the “Where’s Waldo?” itch to understand, but with completely different results: the sculpture allows you to scratch, while the details of the drawings are never completely comprehensible. The slight irregularity of the hand-drawn lines makes it impossible to follow their meaning with certainty when they begin to get dense. There comes a point, before total comprehension, when the viewer has to say, “Enough!” and gives up, leaving the piece like a half-finished crossword. In the sculpture, one has the choice of appreciating the piece holistically, without unpacking its complexities, or, with a little effort, of tracing the scheme of Siquier’s structure to the last joint and component.

Siquier’s big sculpture is far simpler than the structures portrayed in the drawings. Limited by the technical realities of welding together steel rods in real space, the sculpture, though complex, is completely comprehensible. In my mind, I disassembled the room-sized piece into its components, appreciated their clever economy, and packed them into a crate no bigger than a card table. Anyone who has put together IKEA furniture could do it.

Siquier’s big sculpture is far simpler than the structures portrayed in the drawings. Limited by the technical realities of welding together steel rods in real space, the sculpture, though complex, is completely comprehensible. In my mind, I disassembled the room-sized piece into its components, appreciated their clever economy, and packed them into a crate no bigger than a card table. Anyone who has put together IKEA furniture could do it.

It’s the difference between the unknown and the unknowable, and the preference for one over the other is a matter of personality and expectations. Do you like your artistic representations completely lucid, or do you prefer them to be a little misty at the edges? I prefer the constructivist clarity of the sculpture, but it’s missing the pleasant hint of romance and mystery that lurks in the infinitude of detail in Siquier’s drawings.

Incomprehensible, yet seemingly purposeful objects are as fascinating as they are familiar: Texas City oil refineries, Oceanic art, computer circuit boards, and Arabic calligraphy all share a beauty unimpaired by ignorance of their inner workings. Siquier’s works use some of the same techniques to evoke awe as the religious art of the past: he combines the divine, mathematical infinitude of Islamic tile work with the centered, one-point perspective reserved for Madonnas and mandalas to create devotional images dedicated to a majestic vision of techno-urbanism.

In this sense, Siquier’s works are about a human craving for order and understanding, the impossibility of achieving total comprehension, and the beauty of trying anyway. It’s all about the self confronting the unknowably complex world, human-made or otherwise. Siquier places himself, represented thorough his handwork, in the place of the teensy shepherds and hunters who populate nineteenth-century sublime landscapes. Together, we compare notes on an ordered, majestic, and slightly anxious architectonic heaven.

1 comment

I love this work!