Two recent films made by two very different directors have accomplished something a bit rare for a mainstream Hollywood production: They not only bring to the screen glimpses of American history, they are timely commentary on contemporary American existence.

Two recent films made by two very different directors have accomplished something a bit rare for a mainstream Hollywood production: They not only bring to the screen glimpses of American history, they are timely commentary on contemporary American existence.

The wizardry of Spielberg and the ridiculously superb performance of Daniel Day-Lewis in “Lincoln” made me leave the theater feeling like I had just spent three hours with Honest Abe, and “Django Unchained” is among Quentin Tarantino’s best—twisting a revisionist Western tale of the same era into a modern-day sociopolitical allegory.

Beyond a window into mid-nineteenth century America, “Lincoln” shows a society at war with itself—particularly over equality and slavery. Whether you hold to the idea of slavery being the primary dispute or just one of many that led up to the Civil War, the way this film depicts the legislative end of slavery sort of takes your breath away (in the same way the HBO series “John Adams” did with the formation of the Constitution). And of course slavery didn’t then magically dissolve and everyone lived happily ever after. In that way, the film also points to how our country’s modern culture wars have branched out from that historical milestone—to the civil rights movement and beyond issues of race.

I noticed people snickering when lines insulting Democrats went by (such as Secretary of State Seward’s remark of avoiding “the indignity of actually speaking to Democrats”). But I would bet you money that those giggling spectators have little knowledge of how drastically those two parties have changed over 150 years, even as Seward’s comment of Congress being “a gang of talentless hicks and hacks” seems to remain rather true. Those bitter feuds have not died out—they’ve taken on various shapes, bursting out from different corners and pockets of America, funded by quiet interests and inflamed by louder voices that cash in on making things black-and-white, us-versus-them hogwash. Yet any of us who passionately disagree in today’s political circus act could probably agree that “Lincoln” is a great film, and that he was a great president.

Spielberg’s “Lincoln”

Beyond Lincoln being portrayed as a leader with poise and calm during the bloodiest, costliest (in terms of casualties) war in American history, his desire for eliminating slavery becomes the focus of his presidency only after it becomes clear that the war must be won on something—something significant. That something is really the notion of equality—even more grand and complex than abolishing slavery—and it is addressed in a most profound way by Thaddeus Stevens (Tommy Lee Jones) when he is forced to claim that the thirteenth amendment by no means endorses the equality of races (or the sexes even), but simply “equality before the law.”

Now before we get into that, let’s jump to “Django Unchained”—arguably at the opposite end of the spectrum from “Lincoln,” but not so far off as to exclude it from the larger conversation about how the Civil War era connects to the modern one.

Tarantino’s “Django”

“Django Unchained” is a Tarantino through and through: If you’ve seen his movies, you know what I mean. He mixes genre, narrative and humor in a very specific blend. Django (Jamie Foxx) is a slave being transported two years before the Civil War, and is picked up by Shultz (Christoph Waltz)—a well-educated, fast-shooting bounty hunter who needs Django for a job. Becoming a bounty hunter himself, Django crusades to reunite with his lost wife, now owned by a notorious plantation owner at “Candieland,” where he and his Anglo-partner Shultz journey to save her.

Don Johnson plays “Big Daddy,” a charismatic plantation owner whom Django and Shultz visit on a bounty hunt. You might remember him from another Anglo-and-African American duo with a slightly different focus in “Miami Vice.”

First and foremost, the film is a Western. Tarantino himself has stated in interviews that this isn’t a revelation about the cruelty of slavery, though it does depict such incidents with gut-wrenching horror. Tarantino knows that addressing the worst episodes of human history comes with controversy, especially by combining it with genre humor and a heroic narrative. He does in some ways what Cattelan does with sculpture. Tarantino knows where cinema has been and from whence it has come. He stirs archetypes and stereotypes like spices in a pot—turning a traditional gunslinger film into a cathartic story that attempts to equalize the cinematic playing field.

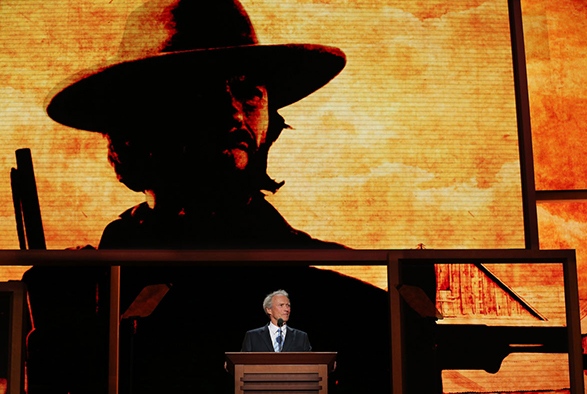

I don’t remember too many American Westerns helping me understand the helpless hell that so many African Americans endured in America for well over a century. The American Western narrative that is embedded almost genetically in the heart and soul of mostly American white men emphasizes and champions the idea of the independent, self-guided hero like Josey Wales (Clint Eastwood) riding his horse just beyond the limits of civility and lawlessness. It’s that cowboy justice mentality—one that a lot of white men identify with—that still holds a heavy weight on the heart and mind of our collective macho identity: Anarchy is hell, but governed society ain’t much better. Best to ride alone, armed and with one eye open. Best not get attached to anything, because even though I’ll usually do the right thing, I’m a real nasty son of a bitch.

Clint Eastwood stands in front of an image of his iconic character Josey Wales as he begins his address to the Republican National Convention in August 2012. Here’s some interesting reading on that.

The Wild Western was born out of the Civil War era—a time when the ideals set forth by the founding fathers broke down into bitter differences about what equality (and a host of other words and sentences written at the end of the 18th century) really meant. So as (spoiler alert!) Django, one of the first true black cowboy-justice heroes, rides away after killing as many ruthless, despicable racist white men as he can (all of whom have been chomping at the bit to punish him in the most self-righteously brutal way, as they do to countless other slaves in the film) one feels a satisfying retribution—a triumphant moment of good over evil as the pure, white-painted plantation home of Calvin Candie (Leo DiCaprio, whose character takes a sordid interest in Mandingo fighting and phrenological superiority of whites) burns to the ground. It symbolizes in a sensational way what “Lincoln” does in an understated way (like when Lincoln subtly utters “slavery is done” near the end of Spielberg’s film). Both gave me goosebumps, and both, like I’ve been saying, point in the direction of the present.

“The white establishment is now the minority,” said conservative pundit Bill O’Reilly the night President Obama won reelection. True, and perhaps not so inflammatory if taken to mean that the electorate has indeed shifted from mostly white voters to a more, say, equal representation of America’s ethnic and gender diversity. But Mr. O’Reilly continued: “And the voters, many of them, feel that the economic system is stacked against them and they want stuff. You are going to see a tremendous Hispanic vote for President Obama. Overwhelming black vote for President Obama. And women will probably break President Obama’s way. People feel that they are entitled to things and which candidate, between the two, is going to give them things? The demographics are changing,” he said. “It’s not a traditional America anymore.”

Apparently, if his statement is taken literally, white men are the only race/gender that don’t feel they are entitled. Women, Hispanics, and African Americans however, do. Really? After contemplating the details of both “Lincoln” and “Django Unchained” (and probably gobs of other historical and fictional content about American history), I’d argue that the ones who have been standing on the platform of entitlement would be none other than the “white establishment.” Those who for decades and centuries chained up and beat slaves, kept women silent from public discourse and participation, bulldozed over native populations, burned the suspicious at the stake and lament up to this very day over “entitlements” that have taken centuries to be granted to those other than white men. Now I don’t for a second hold that all white men are evil (since I am one myself), but I wouldn’t dare insinuate that traditional America is changing because every other demographic than mine feels entitled. That seems like a weak justification (and perhaps a last-ditch cannonball) for what may be the white majority’s denouement.

John Trumbull, Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1776 (commissioned 1817)

Yes, it may have been the white-established consortium of early Americans that wrote “all men are created equal,” but I don’t think it was the white establishment that further demonstrated this principle by any solely comprehensive means. I’m not sure what O’Reilly has in mind when he refers to “traditional America” other than white establishment rule, and I’m not sure I’d want to live in his particular version. (O’Reilly did write a book called “Killing Lincoln” and another, “Killing Kennedy.” I haven’t read either of them, and though the books seem to act as primer-novels about the assassinations of two presidents instead of say, two presidents’ efforts to further the idea of equality—specifically for African Americans—I think even if I did read them I’d still prefer Tarantino’s take on assassination—”Kill Bill.” Oh no I didn’t!)

Which brings me to the controversial part of this essay (you thought you were already in it?). Equality may have nothing to do with race, gender, class or genealogy. In fact, those are the distinctions that define our God-given differences—and find us wanting more regulations to help level the playing field, so it’s claimed. Another controversial idea then is that very thing: Perhaps we all aren’t created equal. It’s a novel idea—and noble one—that we are. But is it true? This is why Thaddeus Stevens’ address (in Spielberg’s “Lincoln”) is so important. Stevens responds to the House during a debate about the thirteenth amendment. His enemies (one of which is Ohio Representative George Pendleton) think that if Stevens will admit that he believes in the equality of all races, those on the fence about voting for the abolition amendment will surely vote no—fearing that blacks, after being granted freedom, will then be given the right to vote and possibly more, say, “entitlements” that whites enjoy. Instead, Stevens restrains his personal conviction for a more profound argument about equality:

“How can I hold that all men are created equal when here before me stands, stinking, the moral carcass of the gentleman from Ohio, proof that some men are inferior? Endowed by their maker with dim wits, impermeable to reason, with cold pallid slime in their veins instead of hot red blood? You are more reptile than man, George. So low and flat, that the foot of man is incapable of crushing you. Yet even you, Pendleton, who should have been gibbetted for treason long before today, even worthless unworthy you ought to be treated equally before the law!”

If Spielberg’s “Lincoln” teaches us anything, it’s that our differences run deep, dark and through the heart: particularly the subject of equality and what that term means both ontologically and constitutionally. The term goes beyond race, gender, class, all of it. Stevens’ remarks in the film suggest that perhaps even two men of the same race are not “created equal.” The term “equality” is then one of the most difficult ideals left to us by our founding fathers (not to mention the term “created”). It might be that we do not come from equality. In fact the reason we strive for more equality in our laws is precisely because all of us don’t start with the same socioeconomic identities, advantages or resources.

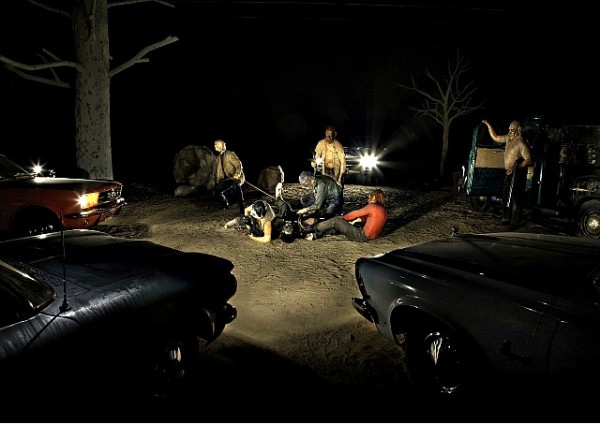

Ed Kienholz, Five Car Stud (1969-72), recently acquired by Fondazione Prada

A year or so ago I was at LACMA, and on special display was an Ed Kienholz installation that had never been seen in America before, called Five Car Stud. It’s probably the most harrowing and nauseating piece of art I’ve ever experienced. You walk into a large dark room, where a life-size depiction unfolds: Five big automobiles surround a group of people at night, the headlights gleaming to illuminate the scene. The figures, as you begin to notice, are all wearing masks—creepy old man and clown-face latex masks. One of them stands with a shotgun by his truck where inside, a woman sits with her hand in front of her face as if she’s about to vomit. Turning towards the center of the scene, you start to get the picture. Two men hold down a black male, two more stand in the distance. One holds a flashlight, the other yanks on a rope tied to the man’s foot. A fifth man hovers over the victim with a knife, poised to slice off the victim’s testicles in an act of supreme perverse brutality. The victim wears a shirt with the “n” word across the chest. Walking around to each of the cars, a young boy sits alone in one of them, staring at the scene through the windshield. You feel a sense of frozen time, like a photograph, but one that you walk around in as if it were a piece of the Akashic record on pause, a sickening reminder of humanity’s undeniably disgraceful, haunted history. A similar scene occurs in “Django Unchained.” A white ranch hand almost has the chance to squalidly enjoy giving Django his castration-punishment moment.

Where’s the equality here? I’ll tell you. No matter what race, country, family, or era you come from, we are all equally capable of savagery. Those with all colors of skin have committed equally atrocious acts of violence. No one is exempt, not even the so-called “white establishment.” Our human condition is wrought with acts like these toward people of different races, genders—hell, even people of the same. Our propensity for violence and hatred knows no constitutionally drawn lines, it has no sympathy for inequality: It is equally horrific whether it’s one enslaving and killing many, multiple torturing one, or brother against brother. We can thank the notion of superiority, not equality, for most of that.

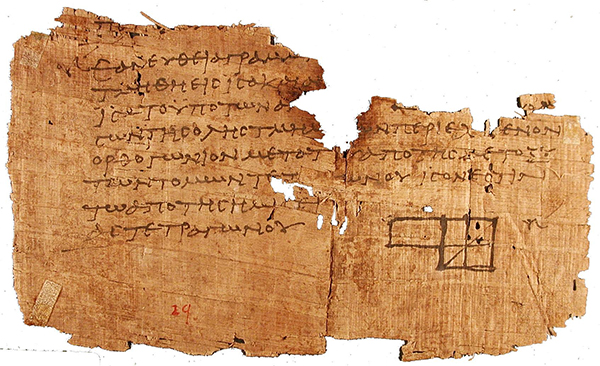

There’s a scene in “Lincoln” where he cites a notion of Euclid: “It is a self-evident truth that things which are equal to the same thing are equal to each other.” He asserts the statement is a mathematical certainty, two thousand years before the self-evident truths of the Declaration of Independence were written. Thus, confronted with both mathematical certainty and the words of his ancestors, Lincoln states “we begin with equality.” However, I don’t think he meant to restate the claim that “all men are created equal.” Instead, I believe he meant that if we are in fact created with, and continue to war over, an infinity of differences, then it must fall to society—and its laws—to strive for equality in the treatment of its citizens.

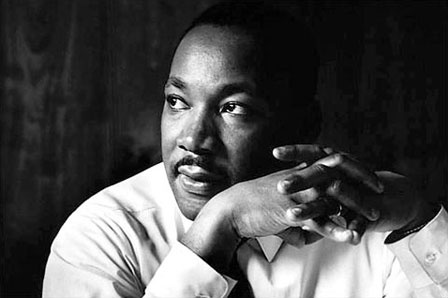

As Lincoln seemed to realize, even if being equally created remained in dispute, we nonetheless deserve equality before the law, which then stems to equal rights and equal opportunity. Surely we are rational, compassionate and responsible enough for our society to begin with that. Because if we do not, we risk the all-too-familiar behavior of superiority of one race, gender or establishment over another. We are equally capable of savage behavior, yes; but also equally able to recognize, evaluate and dignify character (a notion that wouldn’t get introduced for 100 more years), which transcends skin color, gender/partner preference, religious belief, whatever the inherent differences may be.

Our story of equality, our definition of it, is still working itself out. Even if equality is as self-evident and certain as Lincoln and Euclid claimed, it isn’t certain that human behavior will use the notion for our greater good. Thus we have to be reminded of our collective propensity for violence and discrimination, and learn to evolve into the more perfect union we consistently fall short of. Seeing a film like “Lincoln” helped me revisit why the struggle for equality still matters while capturing a tumultuous and fascinating period of human history. A film like “Django Unchained,” while radically different, plows right over the textbooks to make cinematic history. Both films, even with fictional embellishment, reflect our real relationship with the past—and equally our present.

5 comments

I had the same thought about our parties while watching Lincoln: how many Americans understand how the Republicans of the 1860s were radical Northeasterners? And that the conservative white Southerners, the Dixiecrats, depicted in the film would abandon the Democratic party a century later after Civil Rights were passed? The reversal has been almost wholly complete (almost) — so much so that the Republican Senators and Congressmen from NJ and NY couldn’t get an aid package for Hurricane Sandy voted on in the House this week, because they don’t carry the weight of their Southern counterparts.

Agreed Rainey, and also interesting how the “Southern Strategy” sought to take advantage of civil rights/civil war bitterness, and really became the last political refuge for the white establishment. I’m sure there’s shelves of books on this I haven’t read.

John–very insightful article. A pleasure to read. I haven’t seen either film yet, but they both are on top of my list.

I admire your ability to express in words what I have believed but have never been able to express. Insightful thoughts and beautiful writing, Thanks

Touche! This kept me intrigued the whole article, this rarely happens for me! Thank you for sharing your thoughts on these movies, breaks in history, human philosophy, and kindred self awareness. Excellent! So rare, so good.