As a native-Houstonian, Trenton Doyle Hancock introduced me to the work of Philip Guston. As an unaware tween, the mutuality of both artists’ Klan imagery felt more likely to flow from the brush of a Black artist raised in Paris, Texas than from a first-generation Abstract Expressionist and Jewish artist living in New York City. In retrospect, though, that innocent disassociation enacts Hancock’s endearing dream: “I like to think,” he says, “that I’m in Guston’s pantheon, just as much as he’s in mine.”

Toss the big white Klansman in the room aside for a moment, and the kinship still holds. Notice their mutual fondness for fleshy pinks and weightless blues, their graphic playfulness, the heavy-lidded introspection tucked inside punchline aesthetics, their humor as a strategic seasoning for social justice, and, of course, their coherent self-awareness that never takes itself too seriously, but never lets go either.

Though Hancock first confronted Klan imagery in his 1993 The Properties of the Hammer, his awareness of the connection to Guston crystallized later. When printmaking professor Thomas Seawall noted the overlap, he lent Hancock Robert Storr’s 1986 monograph on the artist. And like mythic proximity turned into personal ritual, Hancock slept with it beneath his pillow for nearly two years — a totem, a text, a transfer.

From November 8, 2024, to March 30, 2025, Hancock and Guston’s speculative communion coalesced in Draw Them In, Paint Them Out: Trenton Doyle Hancock Confronts Philip Guston at the Jewish Museum in New York City, a luminous encounter staged as curatorial séance. The show allowed Hancock, in his own words, “to examine the relationship between Jewish and Black cultures, which have been linked historically through resonant experiences with trauma and achievement, oftentimes managing to cope through a symbiotic relationship with one another.”

Through immersive metaphysical fantasies, Hancock excavates resonant signs from our world and reconfigures them into his own. He curates his cosmology from wizardly Klansmen, humanoid deities, alien biomes, and mythic internal organs, all of which populate far-flung worlds with not-so-far-from-home inhabitants.

Philip Guston, “The Ladder,” 1978, oil on canvas, 71 1/2 x 109 1/2 x 2 inches. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. © The Estate of Philip Guston

Even as Guston tilts toward austerity, his compressed spaces hit just as hard. In The Ladder (1978), arguably one of the most emotionally precise works from his final years, he arranges tangled legs beside a monolithic wall. On the other side, his equally ailing wife, peers helplessly. If Hancock bathes us in maximalist abundance, Guston delivers gravity through subtraction. In four colors and four forms — red, blue, black, and white — he enacts heartbreak. Two Gustons, divided by wall and ladder, tethered by geometric ache.

Accept the picture plane as a “what’s the password” portal and internal fantasy confronts recognize external reality. Guston’s polemic I Paint What I Want to See compiles 11 sharp vignettes. The first centers on a 1960 conversation with British critic David Sylvester. Right away, Guston fixates on the plane itself — its resistance, its necessity, its “puzzling” metaphysics. “Without this resistance,” he says, “you would just vanish into either meaning or clarity … and who wants to vanish into clarity or meaning?”

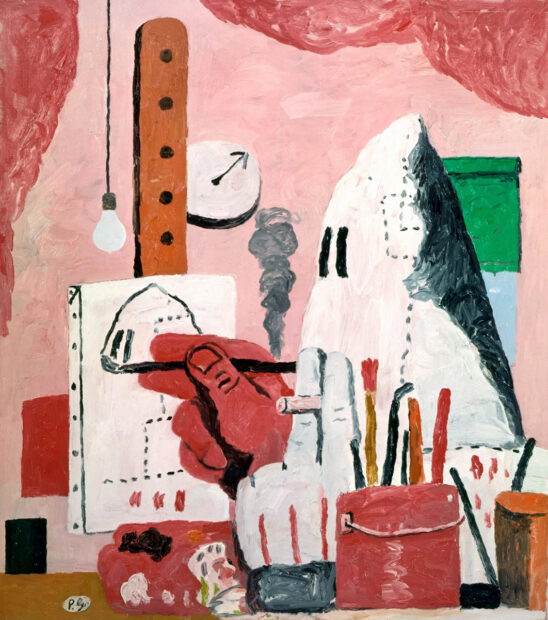

Philip Guston, “The Studio,” 1969, oil on canvas, 71 x 73 3/10 inches. © The Estate of Philip Guston

Guston rejected the tidy cues of self-portraiture. Instead, in The Studio (1969), he renders himself as a Klansman: not as metaphor, but avatar. He implicates himself. He stages the artist not as outsider, but as ghosted participant in a nation unraveling under racialized violence. No buried subtext here, only exorcism. Guston doesn’t just depict the monster: he performs it, absorbs it, wears it.

Installation view of “Draw Them In, Paint Them Out: Trenton Doyle Hancock Confronts Philip Guston” at the Jewish Museum, NY, November 8, 2024-March 30, 2025. Photo: Gregory Carter/Document Art

Because Draw Them In, Paint Them Out coats itself in the volatile pigments of identity, symbol, and affect, we must locate Hancock’s work on that chromatic spectrum. His binaries — Loid and Painter, black-and-white and color — aren’t mere narrative opposites. They’re atmospheric codes.

Loid, the patriarchal figure, absorbs the blunt force of black-and-white logic. He doesn’t just represent oppression; he binds oppressor and oppressed in a single spectral form: half Klansman, half Klan victim. Painter, his maternal counterweight, channels a generative force. She births not just characters, but mythos. Torpedo Boy emerges from her as Hancock’s avatar, his trickster-child-warrior, always in battle with Loid’s return.

As architect of symbolic realms, Hancock tugs at the levers of the real. Like the Greeks before him, he turns myth into metaphor, metaphor into mirror. In Hancock’s cosmology, Torpedo Boy faces bumbling Klansmen wading from the River Styx. The picture plane becomes less a frame, more a membrane. Not a window, but a crossing.

If Guston’s Klansmen, in the wake of 1960s racial terror, offered a bitter prescription, then what legacy might Hancock’s work propose? Not prevention, exactly. Not solution. But maybe a filter, a spell. An image so convoluted it resists endorsement. If Guston’s figures failed to exorcise racism, they at least exposed its symptoms. They still spark controversy, but not for the reasons they should. Guston didn’t paint martyrdom; he painted complicity.

Guston and Hancock use humor not as levity, but to carve uncanny space between critique, complicity, comedy, and collapse.

This humor doesn’t dilute their visual weight; it sharpens it. Hancock’s pink skies and rainbow guts don’t soften the blow of his themes; they lull the viewer just long enough to let the blade slip in. Guston’s lumpy Klansmen don’t absolve; they indict by way of grotesque parody. Their shared humor rejects the binary of innocence and guilt, instead forcing viewers into a third position: that of uneasy recognition. You laugh, and then you wonder why.

Installation view of “Draw Them In, Paint Them Out: Trenton Doyle Hancock Confronts Philip Guston” at the Jewish Museum, NY, November 8, 2024-March 30, 2025. Photo: Gregory Carter/Document Art

In Draw Them In, Paint Them Out, the Jewish Museum doesn’t just curate a show — it orchestrates an afterlife. Guston’s forms, once maligned or misunderstood, return not as relics, but as codes, waiting to be cracked by Hancock’s metaphysical decoder ring. The ladder reappears, again and again, as bridge, as noose, as metaphor for a path both climbed and fallen from. The Klansman figure cycles through masks and meanings. The question is no longer what it means, but how it haunts.

By honoring Guston without sanctifying him, Hancock reframes influence as recursion — a feedback loop. A ritual reenacted in new pigments and proportions. The show resists resolution and, in doing so, fulfills its purpose. Hancock’s maximalism does not overwrite Guston’s minimalism; it listens, it layers, it mutates. The picture plane — once a wall — becomes, in Hancock’s hands, a ritual mirror.

Look too long, and you don’t just see the image, but you see yourself, reflected back, refracted through pink and white and black and red.

And if you look even longer?

The ladder twitches.

Trenton Doyle Hancock, “The Former and the Ladder or Ascension and a Cinchin’,” 2012, acrylic and mixed media on canvas, 84 x 132 1/8 x 2 1/2 inches. Collection of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond.

Draw Them In, Paint Them Out: Trenton Doyle Hancock Confronts Philip Guston was on view at the Jewish Museum in New York City from November 8, 2024, through March 30, 2025.