“She’s alive! She’s Breathing”

-Joe Harjo, Walk With Me

Texas famously boasts of being “The Friendly State.” The motto is adopted from its eponymous name, whose etymology traces back to the Caddo word for “taysha,” meaning “friend.” As coloniality always is, this is cruelly ironic. The state’s namesake is a marker of its bloody beginnings when settlers met the Native peoples’ hopeful bid for allyship with violence. The land also bears such scars of injustices against indigenous peoples. As Eastern tribes were pushed further West to free up land for settlers to claim, Texans were especially land-greedy (clinging to slavery, and thus, to private land, little was federally allocated for Native relocation). This is why there are so few Indian reservations in Texas in comparison to states like Oklahoma, where over 60,000 Native people were forcibly relocated by decree of Andrew Johnson’s Indian Removal Act of 1830, now better known as the Trail of Tears, which resulted in thousands of deaths. In Indian Removal Act II: And She Was, on view at The Contemporary at Blue Star in San Antonio, Joe Harjo (Muscogee (Creek)) confronts the profound impacts that the Trail of Tears had on Muscogee women and other Native tribes, and subverts the devices that have historically been used to homogenize Native people.

Joe Harjo, “A Heretical Act of Resistance – Walking with Babygirl,” on view at The Contemporary at Blue Star. Photo courtesy The Contemporary at Blue Star.

Harjo’s great-grandmother, Babygirl, survived the long walk. However, she arrived in Oklahoma as an orphan because her parents did not. The epigraph is an excerpt from Harjo’s featured video work, Walk With Me, reenacting dialogue between a man and woman that narrates when Babygirl was found and eventually adopted. The work tracks Babygirl’s survival and the women’s maternal draw to the young, traumatized girl. Unable to communicate her name, the woman resolves to call her Babygirl and encourages her to follow them to safety. The woman checks in on her emotional state throughout while the man’s inquiries remain pragmatic and unemotional. Eventually, the woman adjusts her invitation from “walk with us” to “walk with me,” diminishing the man from the rescue effort and highlighting her connection to her. The retelling establishes a framework of familial oral histories as if this is the exact story Harjo’s mother told him, whose mother told her, and whose mother heard a first-hand account from her mother, Babygirl. The woman’s compassion and the conversational mode establish a vernacular perspective of the Trail of Tears in contrast to the colonialist lens that saturates textbook narratives — a recurring call that Harjo heeds throughout the exhibition.

Joe Harjo, “Walk With Me,” on view at The Contemporary at Blue Star. Photo courtesy The Contemporary at Blue Star.

Of the many assaults that systemically disrupted Native cultural and social structures, Harjo magnifies the shift away from a matrilineal society within the Muscogee Nation. The Muscogee developed their clans according to maternal lineage, and women had dignified influence in their communities — until settlers enforced patriarchal structures. In Indian Removal Act II, Harjo reclaims the Muscogee women’s prestige using the same assimilative frameworks that stripped it from them. Crosses and other Christian iconographies are thematic in the exhibition pointing to how the doctrine served a duplicitous role within the colonial conversion agenda. In the photograph Mother at Rest, a headstone in a snowy cemetery bears the simple adornment “MOTHER AT REST.” The wooden frame intersects the composition dividing the subject into four quadrants, forming a cross over the grave. The cross’s dissection of the woman’s headstone, of her memory, demonstrates how Christianity was instrumental in fragmenting Native matriarchal systems under the guise of God.

Joe Harjo, “Mother at Rest,” on view at The Contemporary at Blue Star. Photo courtesy The Contemporary at Blue Star.

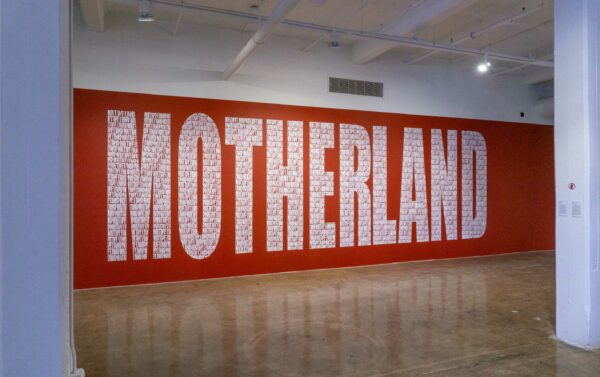

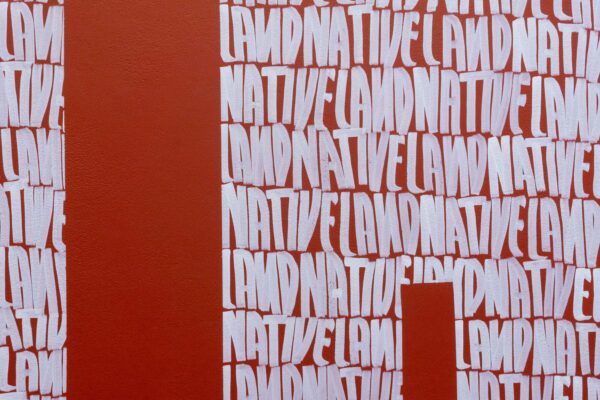

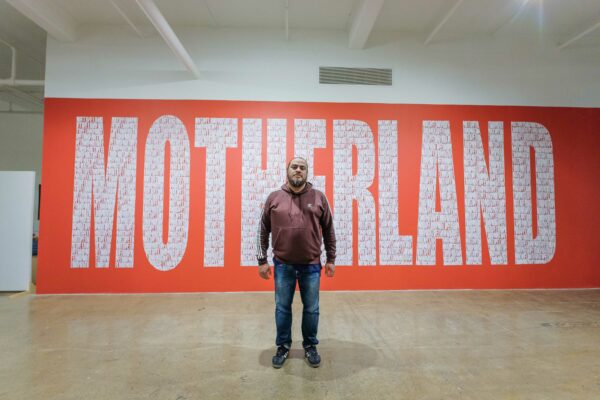

Native Land (Motherland) alludes to education as another ideological component responsible for homogenizing Native cultures. “MOTHERLAND” spans across the large wall at the back of the exhibition space. Painted in white to contrast against the red background, each letter comprises the repeating phrase, “native land.” Activated by the viewer’s engagement, the work requires reading it up close and from a distance. The phrase repetition refers to “writing lines,” a form of punishment often used in schools to discipline children by requiring them to write the same words repeatedly by hand. The text-based work presents a dichotomy in writing as both a historically productive and reductive tool; in the case of Native American Residential Boarding schools, writing simultaneously produced narratives through methods of assimilation while reducing Native customs through cultural erasure. The performative nature of the work considers Harjo’s meditative state in the writing process; with each phrase written, its meaning nullifies — and thus, negates the assimilative objective. However, in its visual form, the message rings clear: this land was, and still is, Native land. Harjo’s designating this as the motherland reasserts the important role that Native women have played historically and continue to play, reclaiming their agency by subverting one of the very practices used to displace their matriarchy.

Joe Harjo, “Native Land (Motherland)” on view at The Contemporary at Blue Star. Photo courtesy The Contemporary at Blue Star.

Joe Harjo, detail “Native Land (Motherland)” on view at The Contemporary at Blue Star. Photo courtesy The Contemporary at Blue Star.

Harjo assigns Indian Removal Act II as The Confrontation in a three-part series, or act. The first, Indian Removal Act I: American Progress, debuted at Galveston Arts Center and served as The Setup. Indian Removal Act III will open at Texas Christian University in March 2025 and conclude the series as The Resolution. As The Confrontation, Indian Removal Act II addresses fundamental conflicts to be resolved in the forthcoming finale. Installed between two pillars in the center of the exhibition space, just beyond the screen for Walk With Me, narrow strips of red fabric bound by a single white seam drape to the floor. To create Land Acknowledgment III & IV, Harjo reconstructed the red stripes from an American flag. By isolating the them from their intermittent white counterparts, Harjo holds up a mirror to the national symbol by extracting and isolating its violent foundations, again subverting the ideological framework that was used to subjugate Native bodies, memorializing the massacred and condemning the colonizers.

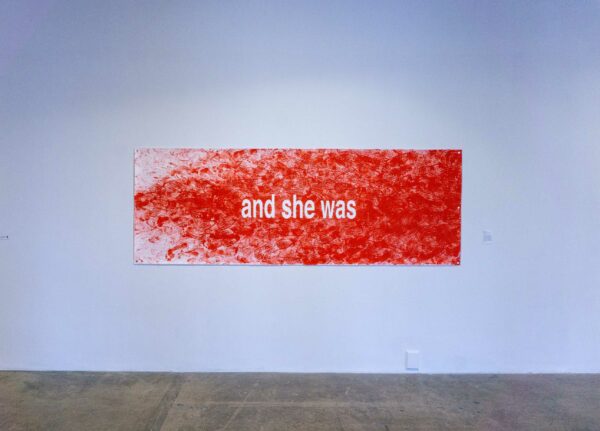

Red emanates from the center of the space and throughout the show, prominently in the work that titles it. In and she was, red, seemingly blood-stained footprints trek across the paper from right to left. The tracks taper off toward the edge as if suggesting their bodies have fallen, honoring all the victims of forced Native removal. Yet through the red viscosity, and she was cuts clearly through, insisting that she still is and heralding the resilience of Native women throughout centuries of trauma inflicted on them through forced displacement and assimilation.

Joe Harjo, “and she was,” on view at The Contemporary at Blue Star. Photo courtesy The Contemporary at Blue Star.

Joe Harjo, detail “and she was,” on view at The Contemporary at Blue Star. Photo courtesy The Contemporary at Blue Star.

Harjo pays homage to the women in his lineage who came before him and the women who supported them along the way. Looking to the future, Indian Removal Act II advocates for the crucial role that matriarchal communities will play in America’s future — especially during a time when women’s reproductive rights are under attack by the Christian patriarchal values that usurped Native land and laid our nation’s foundations, most recently evidenced by The Arizona Supreme Court reinstating a Civil War-era law that bans nearly all abortions. “She’s alive! She’s still breathing!,” the woman proclaims in Walk With Me. While she’s directly referring to Babygirl, her phrase represents the perseverance of Native women and those who provided them with connection and support amid suffering, such as herself. Echoing her invitation to Babygirl, Harjo invites us all to walk with him through the past, present, and future trajectory of Native resilience.

Joe Harjo, “Indian Removal Act II: And She Was,” on view at The Contemporary at Blue Star. Photo courtesy The Contemporary at Blue Star.

Indian Removal Act II: And She Was is on view at The Contemporary at Blue Star through May 5, 2024.