Installation view of “Hanne Darboven: Writing Time” at the Menil Drawing Institute. Photo: Paul Hester

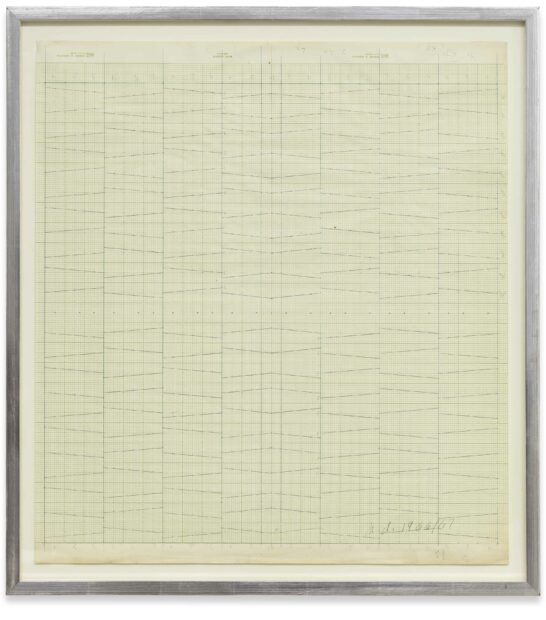

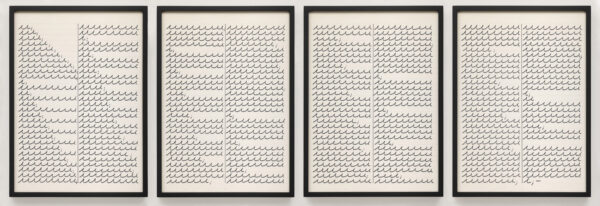

Obsessive partitioning of the world that mirrors our current moment in many particulars is what the Hanne Darboven exhibition is emanating at the Menil Drawing Institute. It is a small affair that still allows a clear idea of the scope and profundity of her vision to form. Darboven’s work on display is a mix of early drawings, videos, and an installation from her peak years. The former presents the beginnings of her career through experiments with visual language that include geometric drawings, arrangements of numbers, and series of pure, asemic writing. Mostly untitled, these works appear as graphs, lists, or series of equations, straight from a science lab. Unlike most scholarship, these schemas and inventions don’t mean anything in particular. They imitate scientific projections, but to what end?

The centerpiece of the show, Inventions That Have Changed Our World (1996), takes up half of the space, giving us the opportunity to immerse ourselves in Darboven’s reverse engineering of Western modernity. The artist doubled as an inspired hoarder, turning her home and studio near Hamburg into a living museum, not that different from Houston’s famous Notsuoh bar, but far tidier. For this work, she collected ten tin figurines of inventors, produced by the German Technical Museum in Munich, bought several sets of related postcards, and created grids of numbers on lined yellow paper that connect to ten decades of the twentieth century.

Half of the inventions in the installation — the telegraph, telephone, camera, phonograph, and the printing press — serve the dissemination of knowledge and, at the exact same time, the creation of virtual realities, mass politics, and other disembodied documents that mimic the world by copying it in a faulty manner. In three years, the Wachowskis would shake up cinema with The Matrix, but Darboven was already there. An image of time, matter, and data as rows of numbers has already existed in her art long before the stoned conversations on whether our reality is but a corporate illusion.

And her reach goes further, I believe, as Darboven unwittingly participates in one of the more interesting arguments of the last century. Reflecting on the role of science in Western civilization at the end of World War I, her fellow countryman Max Weber posited that “there are no mysterious incalculable forces that come into play, but rather that one can, in principle, master all things by calculation.” Weber called this frame of mind “disenchantment,” meaning that the magic is banished by the microscope, the telescope, the printing press, and all the other inventions of the West. His arguments are still debated, but Darboven’s work presents a sideways glance at this process.

Most writings about Darboven focus on the routine: up at 4 a.m., she worked until lunchtime, then break, then telephone conversations with friends in New York and other world capitals, then wine, sleep, start over. In a famous letter to her one-time lover, American artist Sol LeWitt, Darboven says “I do like to write / I don’t like to read.” These utterances were reprinted dozens of times in articles on her work, but there’s another passage in that letter that’s more telling. “This world is real / this world is frightening,” Darboven writes; this is the common core of both her work and the very process of “disenchantment.” If the world is real, it is frightening. The opposite is also true, and attempts are made continuously through religion to somehow present the world as an illusion and ascend to a higher plane beyond this pitiful existence. (The Matrix is one of the more successful recent cop-outs). There are more sophisticated ways to circumvent the world’s materiality. The aforementioned Sol LeWitt, and many of his stateside contemporaries, concentrated on Platonic solids to find truth in geometric beauty. But if you consent to the world’s realness, you have to choose a different direction. To make it less frightening, you break it into smaller pieces. The smaller the pieces are, the less scary the whole, or at least it was so until one of smallest ever portions, the atom, was found to be capable of previously unheard of mass destruction.

Another Darboven motto, “writing without describing,” also attests to her obsession with the real. Descriptions create myths that bleed into each other to the point of indiscernibility, Catholicism into Communism, Protestantism into Capitalism, and so on. What’s real is the space the description takes up, and it is this space for a statement that fascinated Darboven. No matter how profound one’s insights are, they are matter, and, as such, are insufficient to describe the very things they try to. Among other things, Darboven’s work is a perfect illustration of the anthropic principle in physics, according to which we can only observe the universe that is capable to produce and sustain intelligent onlookers. We create observations and descriptions because we can, and not because they’re true.

Installation view of “Hanne Darboven: Writing Time” at the Menil Drawing Institute. Photo: Paul Hester

True disenchantment, therefore, is unattainable. Scientific portioning of the world seems inherently incapable of holding back the deluge of recombinations of facts and fictions that fuel conspiracy theories, spiritual beliefs, social utopias, and other potent brews of mass delusion. The smaller the portion, the easier it is digested and reframed. By showing us the physical parameters of meaning, Darboven went much deeper than most of her colleagues in conceptual or minimalist art. Of course, her privileged position as heiress to a coffee fortune didn’t hurt her concentration on her goals. But the work done is all her own, real — literally — as can be.

Hanne Darboven: Writing Time is on view at the Menil Drawing Institute through February 11, 2024.

1 comment

Wow, this exhibit looks really, really boring. I honestly couldn’t even make it through the article. I can’t believe they spent so much money on a building only to fill it with artwork that no one will want to see. Who is this for?