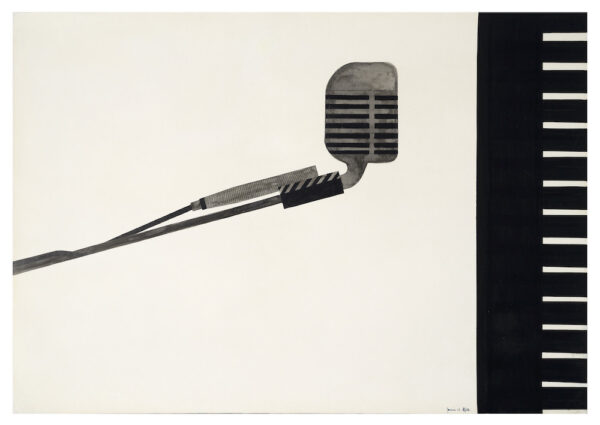

“Silent Revolutions: Italian Drawings from the Twentieth Century” at The Menil Drawing Institute. Photo: Paul Hester

Disegno, the Italian word for drawing, can also mean a sketch, a design, a pattern, or a plan. Beyond its literal definitions, disegno in the 20th century encompasses a wide array of methods, materials, and themes, thanks to the Italian artists who pushed its possibilities further than before. “Italy in the 20th century is marked by an almost uninterrupted series of aesthetic revolutions, starting with Futurism all the way up to Arte Povera and beyond,” says Edouard Kopp, Chief Curator of The Menil’s Drawing Institute, and co-curator of Silent Revolutions: Italian Drawings from the Twentieth Century at The Menil Collection. The exhibition explores the ways that Italian artists redefined this essential art practice.

Alighiero Boetti, Untitled, 1965. India ink and watercolor on paper, 27 1⁄2 x 39 3/8 in. Collezione Ramo, Milan. © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome. Photo: Studio Vandrasch Fotografia,

Silent Revolutions is the first large-scale survey of 20th-century Italian drawings in the United States. With 70 works by 48 artists, the exhibition features a handful of big names like Giorgio de Chirico and Lucio Fontana, but most of its participants will be welcome discoveries for American viewers. The show is co-curated by Irina Zucca Alessandrelli of the Collezione Ramo in Milan, which provided most of the works in the show, with The Menil also contributing a number of pieces from its own holdings.

“Silent Revolutions: Italian Drawings from the Twentieth Century” at The Menil Drawing Institute. Photo: Paul Hester

Why is the show titled Silent Revolutions? “Most people don’t notice drawing at first,” Zucca Alessandrelli notes on a recent video call conducted with both curators. “But it’s really the skeleton and the beginning of every new art movement of the last century.” The exhibition offers a glimpse at the many new types of drawing that arose from an especially tumultuous period in the country. Against a backdrop of world wars, the rise and fall of fascism, reconstruction, and an economic boom, “It’s a century where artists think very deeply about what drawing is as a concept, but also about materials and how to use them,” Kopp explains.

Emilio Scanavino, Untitled, 1969. Grease pencil and acetate on cardboard, 20 1⁄2 x 13 3⁄4 in. Collezione Ramo, Milan. © Estate of Emilio Scanavino. Photo: Studio

We often think of a drawing as something made with pencil or pen on paper. But the artworks in Silent Revolutions encompass a dizzying array of other materials — from watercolor to tempera, gouache, acrylic, and spray paints to colored pencil, chalk, glue, thread, petrol, and even taxidermic eyes. In their drawings, the exhibitions’ artists have employed unconventional processes like embossing, cutting, stitching, pasting, stencilling, frottage, and even burning. And while these mixed methods and materials link the works to practices like painting, sculpture, collage, and performance, the exhibition makes it clear that the goal was to test the boundaries of drawing and to use it to forge something new.

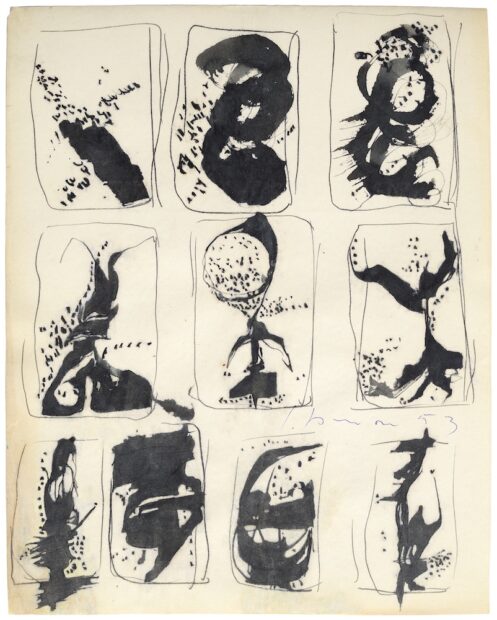

Lucio Fontana, Untitled, Ten Studies for Concetto Spaziale, 1953. India ink, aniline, ink and watercolor on paper, 11 x 8 5/8 in. Collezione Ramo, Milan. © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome. Photo: Studio Vandrasch Fotografia, Milan

One version of this sort of daring drawing appears in Lucio Fontana’s Untitled (Spatial Concept) (1951). In it, Fontana’s light pencil marks on paper are punctuated by a series of exploratory holes that both break and expand the picture plane. Silent Revolutions views drawing as the most immediate and direct product of the artist’s mind, and this piece is evidence of Fontana’s first steps toward a new style. According to Zucca Alessandrelli, these punctured drawings predate Fontana’s signature perforations on canvas.

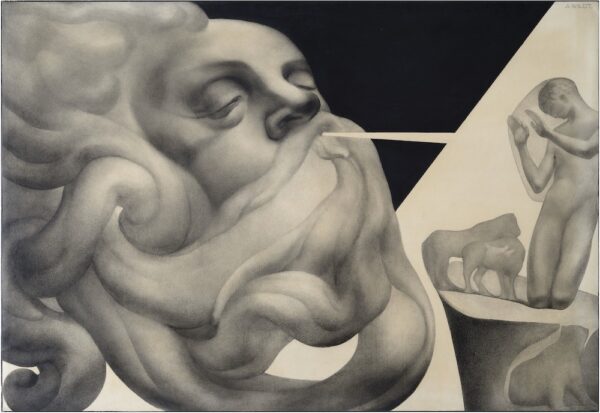

Adolfo Wildt, Animantium Rex Homo, 1925. Graphite pencil and charcoal on paper mounted on canvas, 35 3/8 x 51 1⁄2 in. Collezione Ramo, Milan. Photo: Studio Vandrasch Fotografia, Milan

Adolfo Wildt, also featured in the exhibition, was Fontana’s teacher. In contrast to his pupil’s sketchy, ruptured surface, Wildt’s Animantium Rex Homo (1925) — a graphite pencil and charcoal drawing of God blowing his life-giving breath into man and animals — is all smoothness, polish, and finesse. The wide leap between Wildt’s figurative and narrative work to Fontana’s abstract and torn one demonstrates one of the show’s main arguments: that 20th-century Italy harbored an enormous amount of artistic diversity, exploration, and innovation.

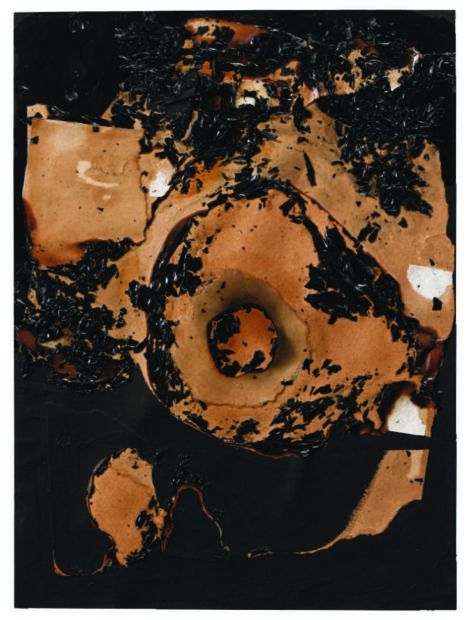

Alberto Burri, Untitled (Combustion), 1957. Acrylic, vinyl glue, and combustion on paper, 13 3⁄4 x 10 1⁄4 in. Collezione Ramo, Milan. © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome. Photo: Studio Vandrasch Fotografia, Milan

An extreme case of this unchained experimentation is seen in Alberto Burri’s Untitled (Combustion) (1957), a flesh and tar-colored whorl of charred vinyl glue and acrylic paint. Made by setting the drawing itself on fire, Burri’s piece is a reaction to the horrors of World War II and a rejection of the Western pictorial tradition that Italy helped establish. “What unifies all the 20th-century artists is a kind of devotion to the Renaissance and the old masters of the 13th and 14th century,” Zucca Alessandrelli says. “They all have Giotto, Cimabue, and Uccello in mind.” At the same time, Burri’s improvised viscerality nods to international art currents like North American Abstract Expressionism and European Art Informel.

Artistic cross-pollination also occurs between drawings and text, especially in the work of the show’s sizable group of female artists. Irma Blank, Betty Danon, and Maria Lai all use a notational, script-like form of mark making that nonetheless remains tantalizingly illegible. “What comes across is a sense of intimacy, but also a delicacy and a reticence towards language,” Kopp observes. “Their works tend to be very quiet, but arguably just as radical as some of the work of their male counterparts.”

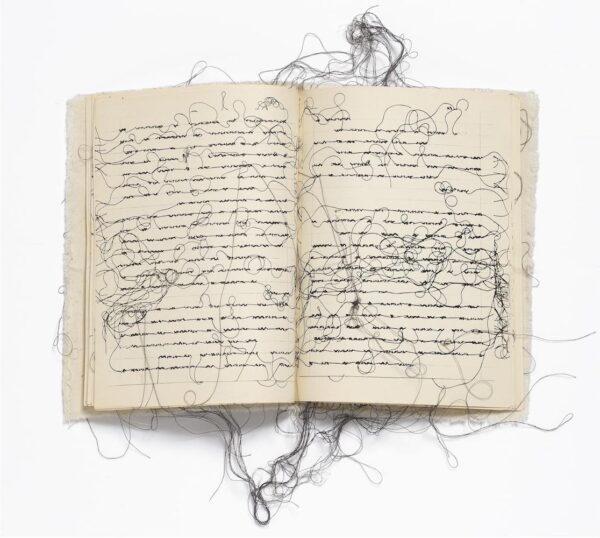

Maria Lai, Diary (Diario), 1979. Fabric, paper, and thread, 9 x 6 7/8 x 1⁄4 in. Collezione Ramo, Milan.© Archivio, Maria Lai. Photo: Studio Vandrasch

In Lai’s Diary (Diario) (1979), the artist has sewn into the pages of a small journal. Configured like dashed-off notes in a diary, Lai’s letter-like lines terminate in loose strings that flow freely across the pages. Lai’s delicately textured document-drawing represents “an expansive notion of drawing that exceeds its own bounds, with the line literally jumping off the page,” Kopp states. Here, and in so many of the works in the show, the definition of drawing continues to grow.

On view at The Menil Collection, Houston, through April 11, 2021. The Menil will host the free, public, online event Symposium on Italian Drawings from the Twentieth Century on April 7, 8, and 9, 2021.