During one of the several visits I made to Art League Houston to see Moe Pender’s exhibition, I climbed into the hammock and swung softly in the afternoon silence, facing the show’s eponymous wall painting, Cuir. I was alone in the gallery, watching a shifting pattern of light and shadow dance across the text caused by reflections of passing cars — the movement of people traveling to and from home. I began to contemplate the complex language game that plays out across the works of art on display.

The sparse installation consists of four large-scale photos, a text-based wall painting, and a usable hammock. The work is deceptively simple. Each piece accumulates meaning, building on the presence of the others. The images, which appear as straightforward landscape and figurative photographs, contain elements of resistance to dominant language tropes. The artist uses linguistic slippages to open up rigid definitions governing traditional assumptions surrounding concepts like home, family, and self.

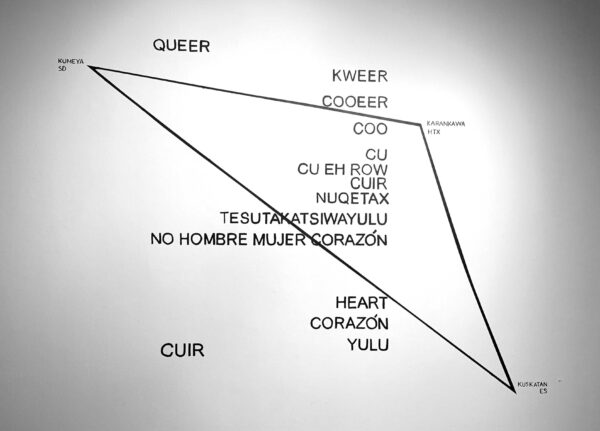

Cuir, the title of both the exhibition and the large wall painting, is drawn from the phonetic pronunciation of queer. The hand-painted wall piece is the key to the way language is manipulated by the polyglot artist, and offers insight into the show as a whole. It speaks to the role language plays in maintaining heteronormative standards, as well as the resistance to this violence. Cuir consists of a triangle charting the three primary geographic locations of Pender’s life, written in both their contemporary and original, indigenous names. Each location was transformed by warfare and renamed after violent takeover. A column of multilingual words cascade down the triangle comprising Nawat, Spanish, French, and English terms, as well as phonetic pronunciations, languages used in each of the points on the triangle map.

In a gendered language (like Spanish), action must be taken to accommodate identities which fall outside traditional usage. New words must be created. As the word queer does not exist in Spanish, a Spanglicized version is used: cuir. Cuir in French means “leather” (in Spanish it’s cuero). The phonetic pronunciations of queer, cuir, and cuero are listed on the wall painting. Additionally, the Nawat word Tesutakatsiwayulu, also included, is a neologism for “non-binary.”

Penders told me more about these nuances: “Nuqetax, Cuir, and Cuero mean leather or skin, in Nawat, French and Spanish. The piece references the languages used in the places I have lived and the themes I am dealing with in the work: migration, queerness, and translation. In Spanish, leather has slang meanings as well: ‘que cuero’ means ‘how sexy,’ or ‘encuerado’ can mean ‘naked.’ I am playing with the connections around queerness and skin or the body that we inhabit.”

In Topical, we see the artist’s shirtless body standing in a bedroom, holding a box fan above their head and facing away from the lens toward the single light source: a sunny window with venetian blinds. The light from the window is overpowering and creates a silhouette. Movement during the long exposure photograph has allowed light from the window to shine through the torso, as if that part of Penders’ body is transparent; their body is open, exposing the linear shadows of the venetian blinds. The artist stands in the center of the image and is framed by elements of the room: to the right a bed with a lamp, to the left a dresser with a water bottle, and a photographer’s loupe set atop it.

In the scene, Penders has applied topical testosterone directly to their skin and stands with the box fan drying their shoulders before dressing and leaving home. The photograph documents an intimate moment of transformation and endurance, bringing it into the public sphere and depicting Gloria Anzaldúa’s concept of nepantla — “the space in between, the locus and sign of transition.”

Moe Penders is a Salvadoran artist who called Houston home for more than a decade. They are currently studying in San Diego; their work explores boundaries established by violence and upheld by language.

Cuir is on display through February 11th at Art League Houston, along with Steve Parker’s Fight Song, Hedwige Jacobs’ The Insides of Envelopes, and Gregory Michael Carter’s We gon put it on the Hood, before we put it on God.