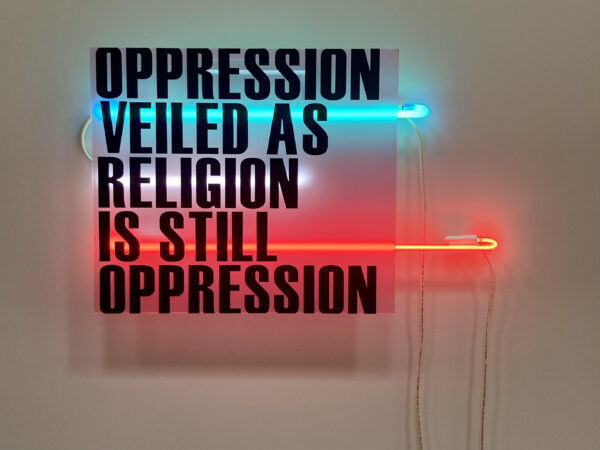

Woman, Life, Freedom (WLF). This simple phrase has become the call for unity and support for the women and girls of Iran as they fight for their fundamental human rights. For decades, gender discrimination has been legally enforced under Iran’s Islamic Penal Code, but in September of 2022, tensions reached an all-time high with the death of 22 year old Mahsa Amini, who died in police custody after allegedly failing to wear her hijab properly. Her tragic death lit an intense movement all across the nation, with many protesters chanting the same slogan: Woman, Life, Freedom. In Farsi, this translates to “Zan, Zendegi, Azadi.”

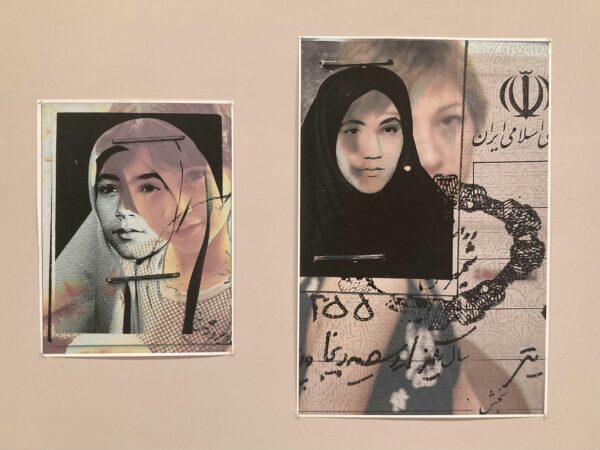

In the Dallas-Fort Worth metroplex, a collective of curators and artists partnered with Pegasus Media Project and came together to organize an exhibition as a direct response to the events in Iran. The show, titled Woman Life Freedom DFW, features diverse artwork from the local Iranian diaspora among pieces by a variety of other artists. The curators’ goal is to “bring together collective expression and witness this historical moment through the exhibition of art…creating an opportunity to hear people’s voices, engage the community in healing, as well as preserve history.” The artwork in the show ranges from painting, photography, and sculpture to performances, dance, poetry, spoken word, video, and so on.

Danié Gomez-Ortigoza with a group, performing “Gisu” at the opening of

“Woman Life Freedom DFW,” 2023.

One of the performances presented at the opening was organized in collaboration with Danié Gomez-Ortigoza, a Mexican-American multimedia artist whose practice — typically composed of performance art, photography, and video performance — centers around the power of braiding and its intrinsic ability to bring people together.

During the live performance, titled Gisu (in Farsi, Gisu means “hair” and Giss means “braid”), Danié explained the power and symbolism of braiding with intention while braiding her hair into red and black ribbons. Behind her, a group of people in long black robes formed a large braiding circle, braiding the hair of the person next to them and connecting it to their own braids as they collectively chanted “woman, life, freedom!” One performer played a handpan in the middle of the circle, while Danié marched, beating her own drum. The performance was ceremonial in nature, but flowed organically. The solemn performers moved rhythmically with one another, creating an fitting atmosphere for expressing the pain of the continued violence and fight for freedom, while also emphasizing the power of community and connectivity.

One of the first installations visitors encounter when they enter the gallery space is No Signal. Created by artist and art therapist Nazanin Ahmady, No Signal is a small room-like space constructed out of PVC pieces wrapped with black fabric. Visitors are invited to step into the space, one at a time, and sit in the single chair that fills the black box. A pair of headphones is available for visitors to wear, which adds an auditory element to the installation; the sound is hard to pinpoint, but can be described as an eerie underwater resonance, one that makes you feel like you’re floating, but also gives the sense of isolation and entrapment. It is unsettling, to say the least. Inside the black room, a single phrase is projected onto the fabric walls — “no signal.”

Nazanin says her installation holds layers upon layers of symbolism and meaning. The box and phrase “no signal” can be seen as a visual representation of what living in modern day Iran feels like — shut off from the rest of the world and without basic rights, like freedom of speech and expression. The structure of the PVC pipes alludes to the bars of a jail cell, touching on the vast number of Iranian protesters that are jailed for their stance against the government and not given representation, a fair trial, or justice. “No signal” is also a message commonly associated with lack of internet connection, and the Iranian government is known to implement internet blackouts during times of civil unrest and rebellion.

No Signal immerses the senses of each visitor individually, creating a singular experience of loneliness and confinement — much like how Nazanin’s experience growing up in Iran was defined by the fear and isolation implemented by the government. According to the artist, creating an experience encompassing the range of emotions that she has been feeling for years was, in itself, an act of release.

On the far side of the gallery, Untitled 2 by Paris Haghighi immediately catches the eye and draws viewers in with its mysterious ambiguity. Born in Tehran, Haghighi is a nonbinary artist whose work explores themes of identity, socio-political issues, and the human condition and experience. In Untitled 2, the repetitious nature of the figure depicted, with each image varying slightly from the others, elicits a narrative of internal conflict. Although the eye contact from the figure is direct, it is not confrontational; more so, it invites the viewer to connect and be vulnerable together. The painting explores the struggles of self-censorship and the courage to speak your mind and share your thoughts. Haghighi says that although their upbringing in Iran was full of nuance, “the rich culture and beautiful old city of Tehran was integral in teaching me how to deal with my solitude and how to navigate life’s struggles.”

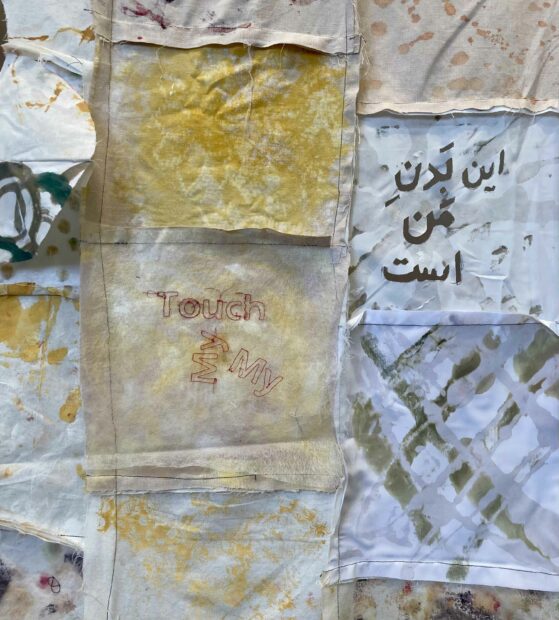

Foreground: Maryam Takalou, “Beyond the Nets,” 2021-2022. Background: Maryam Takalou, “Movable Home, Body,” 2022.

In the middle of the gallery are sculptures by multimedia artist Maryam Takalou, whose body of work centers around territory, placement/displacement, family and identity, and the female body and experience. Titled Beyond the Nets, her four multicolored fabric statues, which can also function as wearable pieces, resemble tiny, furry towers. The artist activates the sculptures by wearing them, much like a veil, reclaiming her voice and the feeling of being “caged in.” Made from small cloth strips, the structures immediately reminded me of the work of Nick Cave, as they take on an identity of their own within the gallery space.

On the wall next to her tiny towers is a huge stretch of fabric, patched together much like a quilt. “Growing up, I remember sewing by hand with my mother and grandmother,” says Takalou. “Women gathered to sew as a form of meditation.” Each patch of fabric is an actual piece of her own family’s clothing, representing each family member and essentially forming a family portrait. The squares are individually detailed with paint, stencils, embroidered text (in both English and Farsi), and sections are cut out in circles — perhaps alluding to the metaphorical holes that form overtime within a family. Takalou’s pieces are as intimate as they are intricate.

One of the most unique features in the exhibition is the connection between two works done by mother and daughter artists. The first piece is an intense and overwhelming instrumental song composed by Shayan Javadi, titled Persimmon Tree. Accompanying the progressive metal song is a surreal, psychedelic, animated music video by Ben Levin, centered around images and motifs from Javadi’s childhood in Iran and the fields of persimmon trees she encountered there. The video follows a character, who has an evil eye for a head, on an epic journey through a universe of beauty and mayhem.

Javadi was only 14 years old when she immigrated to the U.S. from Iran with her mother. Her musical composition expresses “the confusion and eventual acceptance” of her Iranian heritage, as well as her gender. In 2022, Javadi came out as a transgender woman, just months before the mass protests in Iran took place, making the WLF movement all the more personal. The melody of the song is fast paced and somewhat haunting, conveying an immense amount of pain and struggle. The persimmon fruit signifies not only her Iranian culture, but also her transition and transformation.

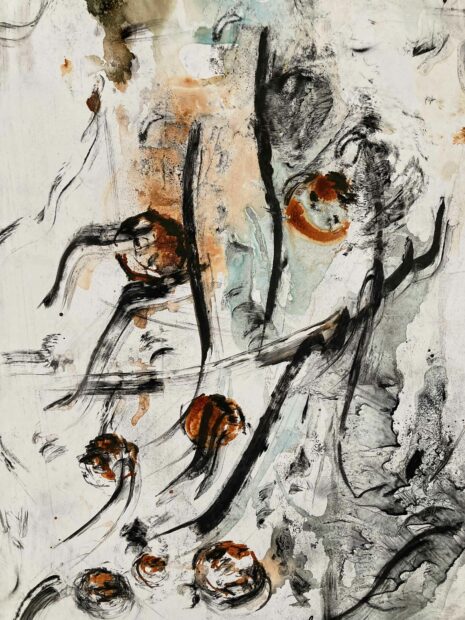

When Javadi first shared Persimmon Tree with her mother, the artist and art historian Marjaneh Goudarzi, almost a year ago to the date, Goudarzi began incorporating persimmons into her own paintings as a way of empathizing and sharing in her daughters pain, while also remembering the time they shared together in Iran during Javadi’s childhood.

Goudarzi’s expressive paintings incorporate a mix of images, Farsi characters, symbols, and muted colors to create a single representation encompassing a montage of both her and Javadi’s emotions. Each brushstroke carries its own weight. Goudarzi says that her series of paintings, titled Persimmons, is about “showing her pride in being a mother of a brave transgender daughter,” and is a tribute to all individuals like Javadi who are living in Iran and have to fight for their fundamental human rights.

Together, Persimmon Tree and Persimmons showcase an intergenerational dialogue between two Iranian women as they navigate their own struggles and transformations, and share in each others’.

This timely exhibition is not just important for its larger contribution to the Woman, Life, Freedom global movement, but it is also an incredible insight into the Iranian diasporic community within the DFW area. It is local, independently curated exhibitions like these that really evoke the essence of a political movement and the community leading it.

The exhibition is on view from January 7 through January 21, 2023 in the Main Gallery at the Irving Arts Center, and will travel to The Fort Worth Community Arts Center from February 6 to February 25, 2023.

Emma S. Ahmad is an art historian and writer based in Dallas, TX.